Interview with Mark Greenside, Author of (Not Quite) Mastering the Art of French Living

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

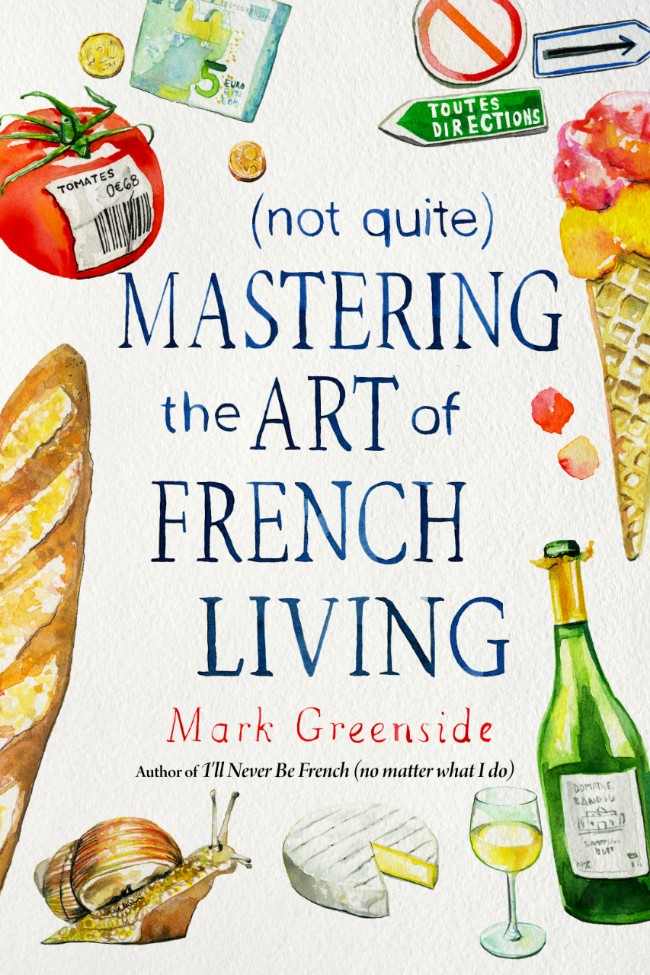

Mark Greenside is the author of two books about his part-time life in Plobien, a village in Finistère, Brittany. I’ll Never Be French (no matter what I do), his 2009 memoir, tells the story of how, to his surprise, he found himself buying a home in a country he didn’t even want to visit in the first place, but ended up falling in love with in just a few short months. His latest book, (Not Quite) Mastering the Art of French Living, is a collection of stories about his adventures (and misadventures) in attempting to master the challenges of daily life in France, arranged thematically into chapters on driving, shopping, banking, eating, entertaining, getting sick, and speaking French. Each of the chapters details these attempts in true stories that anyone who has ever attempted to do any of these things in France will surely appreciate and identify with. Greenside’s self-deprecating sense of humor is often laugh-out-loud funny (think Thurber), but his stories are also full of a deep and genuine affection and respect for French people and their ways. (Which is not to say that he can’t see their foibles as well…) Each chapter ends with a very helpful, informative, and quite practical list of “10 Things I’ve Learned About…” Greenside recently took the time to answer Janet Hulstrand’s questions in this exclusive interview for Bonjour Paris.

Janet: What do you love most about France?

Mark Greenside: I love what most people love about France, Brittany, Finistère, where I live: the visual, gustatory, people pleasures of daily life. I love the flinty, glittery granite houses, walls, viaducts, and bridges; the yellow and green moss splotches on black slate roofs; wild heather; potted geraniums; red, white, and blue hydrangeas the size of bowling balls; Belon oysters; fresh-from-the-sea mussels, crab, lobster, langoustine, St. Pierre, sole, and monkfish; pre-salted (pré-salé) lamb that lived and ate on the salt marshes of Ouessant and Mont-St-Michel; filet mignon du porc; warm, fresh bread with friend-made strawberry, apricot, cherry, or quince confiture and demi-sel fleur de sel butter straight from the Guerande; the cider, chouchen, and the wines of the Loire, especially Muscadet Sevre et Maine Sur Lie; and the crêpes—a nearby restaurant boasts 530 varieties! And I love the kouign amann, fruit tarts, gateau Breton, and strawberries from Ploustel, the sweetest strawberries in the world; and the huge horizons, stormy weather, starry starry nights, misty silvery days; and the sea, and the light—the luminous northern sea light painted by Monet, Seurat, Signac, Gauguin—and the people: the tough, stubborn, curious, dreamy, romantic, nostalgic, anxious, nervous, engaging, helpful, pessimistic, humorous, conservative—meaning safe, not political—people.

Of course, I love all of this—what’s not to love?—but what I find most extraordinarily loveable is me. I love who I am, who I become, how I am in France, Brittany, Finistère.

Like all love affairs, being in France, like being with Donna, my wife, makes me a better, nicer, kinder, more thoughtful, more generous, forgiving, accepting, open, braver, appreciative, adventurous, trusting, embracing, wondering, thankful, grateful, graceful, fun, and funny person. With both my wife and in France, I accept being dependent—a state I normally loathe. I’m open, willing, positive, and I judge both myself and others less. My brother says I’m a nicer person since Donna entered my life 23 years ago. Donna says I’m a nicer person when I’m in France. I say, what goes around comes around, and I’m a better person because Donna and France both came around, and then let me stay.

Janet: What drives you the most crazy?

Mark: I’m embarrassed to answer Time and Order, lack of punctuality and efficiency, which mark me for the American that I am.

Nothing happens quickly or too soon in France, except maybe death. There’s no such thing as a one-minute double-park, I’ll just hop in, grab a loaf of bread, bottle of wine, cookie, and be right out kind of moment. (The double-parking part does exist, but not the one minute.) Every purchase involves a wait: getting into a line that’s not a line, but a wedge; the salesperson having a conversation with everyone in the wedge; waiting while people search for coupons, or a checkbook, or the exact change in the smallest units of coins possible. Fast food is not fast. 24-hour service is 72-hours. A ten o’clock Monday morning meeting happens at 2:00 Monday afternoon, if I’m lucky. It could also be Tuesday afternoon or the following Monday, and sometimes it never happens.

Then there’s the poor signage. Too often, signs don’t exist at all: like I’ll be in Centre Ville looking for directions to the N-165 highway, the major thoroughfare in the area, and there are no signs. There are signs to the next village, to the village dump, the industrial zone, the farm down the road, and to restaurants, hotels, and chateaux—but not to the highway that gets you there, which means I’m often driving in circles around roundabouts or on small country roads—the slowest, most complicated, redundant, confusing way to get from A to B, which brings me back to Time and Order. Amazingly, though, these are also the most beautiful routes, taking me through 16th century stone villages, past fields of grain and bucolic cows, along the coast—bringing me back to things I love.

Janet: What do you have to say about the belief that French people hate Americans?

Mark: It depends on where and when. The first time I was in France, I was in Paris in 1967. It was De Gaulle time and the war in Vietnam was raging. De Gaulle was a cultural nationalist, advocating for and representing the beauty and superiority of French everything, and the war in Vietnam was a universal disgrace and disaster. Put the two together and being an American in Paris was not like the movie—but that was 52 years ago, and things have changed.

Since then, I’ve been to Paris many times and have never experienced any of the hostility and contempt that I felt the first time. Plus, I live in Brittany, in a rural area. There, I have had older people come up to me and shake my hand and thank me for what America did for France in “The War.” People generally thought Bush Jr. was an idiot and think Trump is worse: ignorant and dangerous, but the French people I’ve met separate their feelings for the government and government policy from individual Americans, thank God.

In my experience, in Brittany, there is a hierarchy of foreigners who are disliked: Germans, by older people; Brits, especially those who seal themselves in English compounds, refuse to speak French, and continuously belittle France; Belgians, who are thought of as not too bright; Italians, thought of as French on steroids. But the most universally disliked, mistrusted, and verbally abused people in all of France are Parisians. Wherever they go. All the time. Everywhere in France. Americans, though, are doing OK.

Janet: What’s the biggest mistake Americans make when interacting with French people? And what do you think are the biggest differences between Americans and the French?

Mark: Most American-French interactions, I believe, are commercial—buying this, renting that, reserving something, ordering something else—which is problematic, as Americans want friendly, speedy, expert, efficient service, and French people think commerce is dirty. That’s why in France there’s the mandatory Bonjour and Au revoir, hand-shaking, cheek-kissing routine, and all those long (pointless to Americans) conversations about the weather, family, health, your neighbor, garden, trees, how you cooked your chicken last night…. The greetings and partings and touching and talk minimize the commercial and maximize the personal, which is what French people like, and what drives impatient, in-a-hurry, have-someplace-more- important-to-be Americans nuts. It’s a paradox: Americans, who want speed and efficiency, also want smiles and pleasantry, and French people, who want transactions to be personal won’t be phonily friendly as they provide totally professional—French professional—service.

Another difference that causes problems is the American belief that the customer is always right, and that customers have rights. In France, neither is true. You are not always right—especially if you are a foreigner—and you have no rights. Try returning something you bought, never used, and never opened. Ha!

There are also differences in language. Americans speak in superlatives—things are best, first, greatest, largest, most. French people speak in bon: bonjour, bon shopping, bonne vacance, bon dimanche, bon santé, bonne chance, bon temps, bon fête, bon, bonne, bien—and if it isn’t bon, it’s pas mal (not bad), or merde. French people reserve superlatives for food, art, history, football, and their bodily pains and functions, which is another paradox. Americans, who speak in superlatives about most things, answer the question, Ca va? (How are you doing?) with “Ok, not bad, all right,” whereas French people will actually tell you how they are doing, organ by organ, in superlative detail.

Then there’s humor: Americans like self-deprecation. It’s humbling for those who don’t feel humble. French people hate it. To them, it is not funny. It is belittling and demeaning. In the U.S., it’s not polite to make fun of others—even if/when they’re funny. In France, making fun of Belgians or Italians or Americans is just fine; but don’t try to make fun of them—unless you really know them, and even then not too much.

There is also the matter of tone. French people speak with great authority about things they know a lot about and things they know very little about. It doesn’t matter to them. What matters to them is how you say something. What you say is something else. In France, it’s most important to say something well—cleverly, authoritatively—and intelligently, and interestingly. In the U.S., it’s often the reverse: the more you know about something, the more qualified you are when speaking about it—like the more you know, the more you know what you don’t know. In France, the more you know, the more you know.

You can see why this could lead to mistakes and problems.

Janet: What do you think is the biggest fundamental difference between the American way of life and the French way?

Author Mark Greenside. Photo: Bruno Lamézec

Mark: Attitudes about money and work.

French people love money and what it can buy as much as Americans do—maybe even more, as they tend to be more frugal and cost-conscious, and for years (until the 1990s) they had so much less. The difference is not the love of money, but what French people will or will not do to get it.

I’ve been in stores of all kinds and sizes, ready to buy, and the owner or manager ushers me out—or won’t let me in—because it’s lunch time or closing time or too early. Same thing at restaurants. I’ve arrived at 1:50 or 2:00 with 4, 6, or 8 people for lunch and have been told lunch is over (fini) and the restaurant is fermé. In the U.S. this is nearly unheard-of behavior. In the U.S., what matters most is the sale, the income, the money. In France, what matters most is lunch.

In the U.S., one of the first things you ask someone you meet for the first time is, “What do you do?” and unless you know the person long and well, the answer largely determines how and what you think of the person—which is exactly why French people (especially non-professionals) don’t ask, and don’t want to be asked that question. In the U.S., we live to/for work, as it consumes the bulk of our time, thoughts, and energy. In France, land of joie de vivre, people work to live, which is why they’d rather talk about their hang gliding, Western dancing, bee hives, or zucchini than their work as a coiffeur or fonctionnaire.

Work is important, and people work hard and want to be professional or artisanal and excel, and services—when you can get them—are usually excellent, but for French people it’s not about the money—even when it is about the money. It’s about life, living, joie-de-vivre, which is why the store won’t stay open, and the restaurant won’t serve me, and why Jacques doesn’t want to tell you what he does. He is Jacques, not the coiffeur. I have dear friends I’ve known for 20 years, and I have not the slightest idea what they “do,” but I know all about their kids, the house they built, their favorite recipes, and their passion for bicycling. This is what matters to them, not their jobs—even though without their jobs they wouldn’t have the bikes and biking outfits that must have cost them thousands of euros—even if they bought everything on sale, which I’m sure they did.

In France, employees work 35 hours a week, receive mandatory, annual five-week vacations, retire at age 62 (at least for now), enjoy 11 official holidays per year, plus many other official leaves; and are among the most productive workers in the world. That’s joie de vivre.

Janet: In what ways are you different in France and in the U.S.?

Image credit: Pexels, Andre Furtado

Mark: I’m nicer, more optimistic, more open, more accepting, and more adventurous—all out of necessity.

I’m nicer because I’m illiterate: I can’t say or write what I’d say and write in the U.S. So instead of trying to get the first and last word, as I usually do, in France, because I can’t argue or gripe, swear or whine, I simply accept. After all, this is “their” country, and this is how “they” do things, and I’m here—comfortably and happily—as “their” guest, and my parents taught me to be polite in other people’s homes. As an almost 30-year guest, I’ve learned French ways and I’ve learned my place, and knowing both has made me happier and more content than I am in the U.S., where I’m often angry—especially when I read the papers or watch the news, neither of which I do when I’m in France.

I’m also more optimistic in France, which is odd. In the U.S., where I have language, skills, resources, contacts—and have been a moderately successful shaker-upper—I expect the worst, leaving me feeling my glass is ¾ empty. In France, where I have moron language, few skills, fewer resources, and am completely dependent on others, my glass feels ¾ full.

Dependency, which as a semi/demi Alpha male I abhor in the U.S., makes me nicer and more optimistic in France, because the people I depend on always come through. My friends in the U.S. would always come through, too, if I let them, but I don’t. In the U.S., I try to do more than I can and often get in trouble, get angry, and fail—especially if computers or electronics are involved. In France, over a much wider range of issues—from banking, insurance, and shopping to plumbing—I call Madame P, Bruno, Françoise, Sharon, Jean, Gilles, Tatjana, Ella, or Rick and s/he tells me who to call, and no matter how long or how many tries it takes, it turns out right. It turns out right in the U.S. also, but there I expect it to turn out right, and I resent whatever obstacles and difficulties I had to overcome to make it right, which is why my glass feels ¾ empty. In France, I always expect problems and delays and difficulties, so when everything works out in the end, I’m happy, and my glass is ¾ full.

Janet: How in the world do you have the courage to cook a meal for French people?

Image credit: Unsplash, kate5oh3

Mark: Ignorance and fear.

How many times can you eat at someone’s house and not reciprocate? At what point do I cross the line from being incompetent to being rude, which in this land of protocol, is absolutely the last thing I ever want to do or be. The difference, I’ve learned, is will. If I’m willfully negligent, I’m rude. If I’m blindly incompetent, I’m pitied, and helped. Thankfully, it’s clear to most French people that I don’t have the skills to be willful. Thankfully, they recognize that and that my intent is good, and they respond with pity, advice, and help.

My earliest culinary adventures were barbecues. Easy enough. I set the table and made a salad, which turned out to be not so easy, as I put some ingredients in that French people didn’t think belonged. I filled the grill with charcoal, drank a Ricard or two, and waited for my guests to arrive, which they did, 30 to 40 minutes “late,” which in France is right on time. They came, they saw, they drank, and God bless them, they helped. The men—French men—took over, as barbecuing in France, like going to war, is mostly a man’s job. They watched the grill, cooked the meat, and served it—making sure no plate was ever empty—and the women and I cleaned, and everyone was happy.

After many years of barbecues, I thought I should do more. I didn’t want the men to feel that every time they came to my house, they would have to help me, and I didn’t want the women to have to clean, as none of them would let me help at their house. This was about the time I discovered Picard. I invited friends for dinner and served prepared food—essentially high-end frozen dinners—figuring that whatever Picard cooked would be better than what I did. And it was—and I’d still be serving Picard meals if I could, but I can’t.

I invited Bruno, Françoise, and Jean-Claude for dinner and served five different thin-crust, professionally-made, restaurant pizzas still warm from the pizza oven. It was delicious, and with a proper French salad of lettuce, lettuce, (and lettuce only!) and plenty of wine, I thought the evening a culinary success until the next day, when Bruno told me that if I invite people for dinner, I really should cook. He added that if I needed help, I could call him.

It took me a while, but I now have a system. I do what I do with every difficult, fear-of-failure, seemingly impossible task I begin: I break it down to its component parts and start with the easiest first. Some of the details of how I learned to serve a full French meal are included in (Not Quite) Mastering the Art of French Living.

Image credits: Unsplash, jamesharris_photography

As far as I know no one has gotten sick after a meal at my house and no one has refused to return. Those are good omens, I think, I hope, and I pray; though I still go to their homes ten times more than they come to mine.

Janet: What advice do you have for Americans planning to visit France?

Mark: Learn how to say hello (bonjour), good-bye (au revoir), and thank you (merci), and say these things a lot—to everyone, in every encounter, every day. That covers the basics. If you add have-a-good-day (bonne journée), good evening (bonsoir), a few “yeses” (oui), a few “goods” (bon), and a “for sure” (bien sûr) you can have a 30-minute conversation with any French person, as s/he will be delighted to tell you what s/he thinks, because (1) You are agreeing with what s/he is saying—(oui, oui, bon, bien sûr); and (2) You’re a great listener. More than 30 minutes and you’re on your own….

Over the years, I’ve had many satisfying conversations with French people in which I didn’t understand a thing: I was happy because I didn’t make a fool of myself or show my ignorance; they were happy to have the opportunity to expound to a willing, engaged, and appreciative listener. A win-win if ever there was one.

Purchase this book at your local independent bookstore (in Paris, we recommend The Red Wheelbarrow, San Francisco Books, Shakespeare and Company), or on Amazon below:

Love Paris as much as we do? Get some more Paris inspiration by following our Instagram page.

Lead photo credit : Image credit: Unsplash, stevenlasry

REPLY

REPLY