Street Art at the Petit Palais? Mais Oui!

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 80 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Street art on show at the Petit Palais? It might sound unlikely, but it’s true and it’s proved so popular that the exhibition, We are Here, has just been extended until January 19th. So, if you like the idea of discovering urban art among the classical statues and romantic paintings of the museum’s permanent collection, then you still have time to go and see if for yourself.

It’s an attention-grabbing idea. Some 200 works, all commissioned especially for this exhibition, are on display, representing many of the biggest names in street art from across the world: Shepard Fairey, Invader, D*Face, Seth, Conor Harrington, to name just a few of the 60 artists represented here. In this Belle Époque building, where the City of Paris displays the cream of its art collection, these urban artists are exhibiting their graffiti and their subversive takes on current issues. Annick Lemoine, director of the Petit Palais and co-creator of the exhibition, explains that “the hanging of these monumental works of street art in our superb 1900 building is sure to surprise and amaze our visitors.”

Petit Palais. Photo: Marian Jones

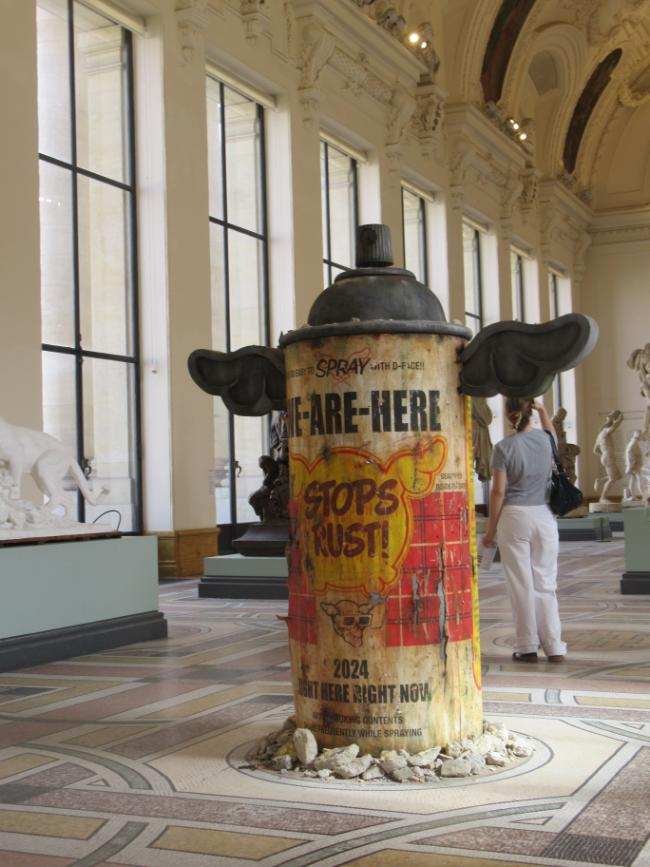

The shock is immediate. Perhaps you know the Petit Palais and can picture the sculpture gallery which leads from the entrance hall, with its carved stone ceiling, frescoes and rows of majestic statues. Imagine then, that to enter it now you must first pass a giant spray can, one of the tools of choice of the new artists who’ve been invited to share the space, those whose stated aim – printed large on the can, in case you were not aware – is to “create, annoy, destroy.” Across the back, in large letters are the words “Stops Rust.” Boundaries, it seems to say, will be pushed.

Spray can at the entrance to the exhibit. Photo: Marian Jones

Intriguingly, the newly imported works are scattered amongst the statues and paintings which are usually here. Some are immediately arresting: Seth’s Napoleon is drawn in the style of a child’s Playmobil figure, recognizable only by his tricorn hat as he sits staring down into a deep well. Or is he on top of a cloud? Either way, his surroundings are pink, white and (mainly) blue. Perhaps a “corruption” of the tricolore colors? A little later comes a female version, wearing a hard hat in a similar setting, but where pink is the dominant color. I only realize she represents Marianne when I read the painting’s title.

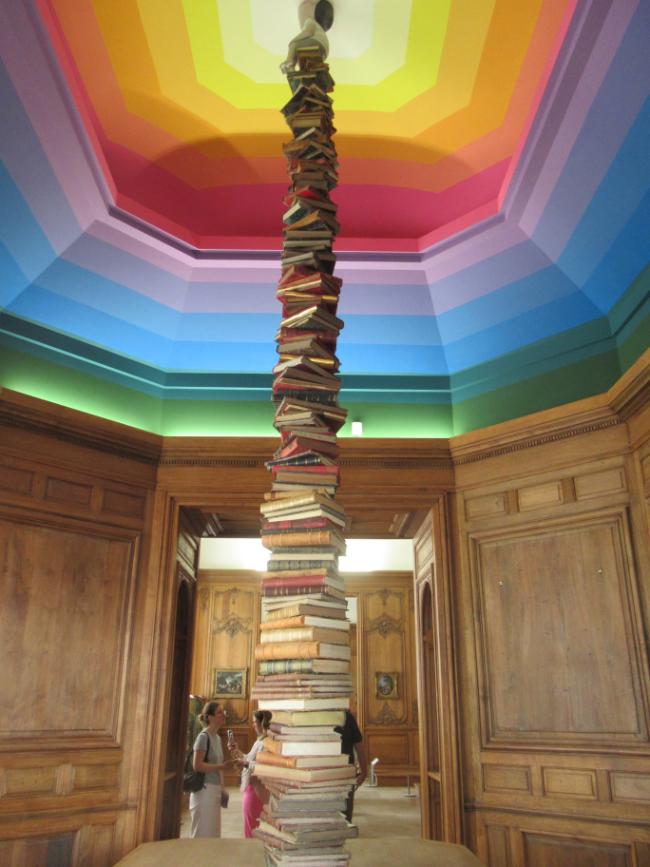

In a little space connecting two larger rooms is The Tower of Babel, a teetering pile of books reaching up and up to a ceiling glowing in rainbow colors. Being a bibliophile, I rather like this and wonder if its message is one about knowledge and enlightenment. The artist, Seth again, has left some explanatory notes. He sculpted these volumes in resin, he says, as a tribute to the books he has loved, especially in childhood, which have taken him to other worlds and helped him “escape the grey of the everyday.” In this world of screens and images, he explains, it will never be possible to “escape the power of words.”

“The Tower of Babel” by Seth. Photo: Marian Jones

In some pieces, the artists have chosen to recognize past influences, perhaps in tribute to the prestigious gallery where their work is being shown. The American artist and activist Shepard Fairey explains that his Bliss at the Cliff’s Edge deliberately references his “vision of a 19th-century romantic painting,” but he has also given it a modern theme. Two figures sit under a beach parasol, looking out to sea under a blustery red sky, but their gaze falls not just on the waves, but also on an oil rig. He wanted to draw attention to the world’s environmental problems because, he says, “we are on the edge of a precipice.”

“Bliss at the Cliff’s Edge” by Shepard Fairey. Photo: Marian Jones

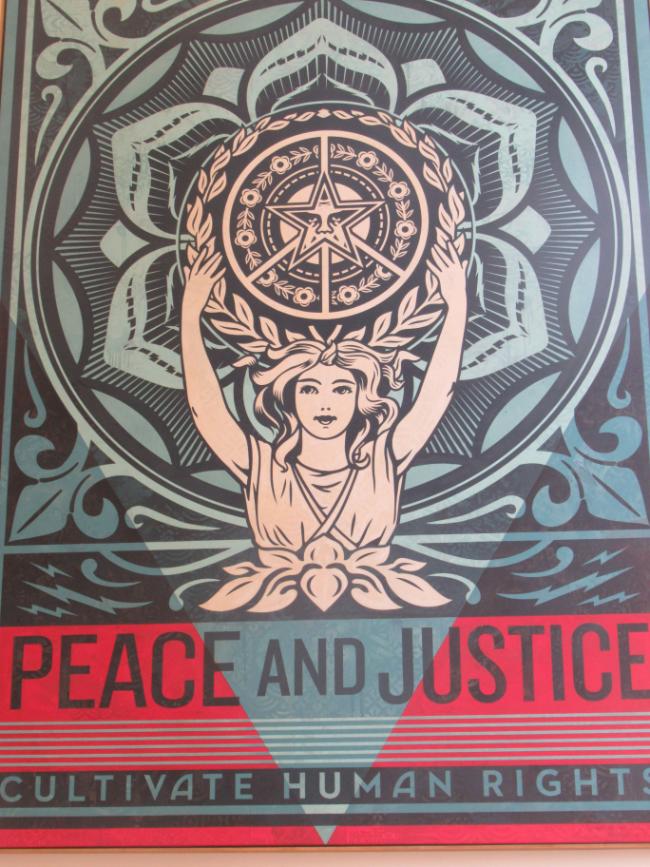

Fairey’s Peace and Justice is inspired by art nouveau and also references the peace protest posters created during the Vietnam War of the 1960s. His Peace Fingers Geometric, also here, features the peace hand gesture picked out in a white floral motif against a background of color blocks in vivid red, orange and blues, almost, but not quite, the colors of the American flag. He created it, he explains, as his reaction to the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. He has recently re-imagined the piece, using different colors, to reference Ukraine.

Sometimes, the message is reinforced by the careful juxtaposition of a new piece and a well-known one. Paul Delaroche’s iconic painting of triumphant revolutionaries on July 14th, 1789, Les Vainqueurs de la Bastille devant l’Hôtel de Ville and Shepard Fairey’s Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité hang side by side. The latter was originally created in 2015 as a response to the terrorist attacks at the Bataclan. Fairey designed a striped background in patriotic blue, white and red beneath an art-nouveau style face of Marianne, representing the republican values he wanted to support. But this version is a new one and the reason behind that illustrates a key theme of the exhibition, namely dialogue, be it between different sections of society or between the past and the present.

The original piece did not feature the blood-red teardrop now falling from Marianne’s eft eye. That was added by activists when a large version of the work was installed in the 13th arrondissement. They said it was a protest against government measures strengthening security. The artist responded that he understood why they had done it and when creating this version for the exhibition he added the tear himself. Fairey has used the piece to comment politically, donating a copy of the original version to Président Macron, but criticizing its appearance in a promotional video filmed by the Rassemblement National. That, he said was a “nationalistic interpretation” and went against his hope that the image would promote “fraternity and living together.”

Sometimes the approach is more questioning than didactic. Connor Harrington’s Down with the King uses portraiture to ask who is, and perhaps who should be, in control in society. His monarch is based on Louis-Philippe, France’s last king, depicted in a crown and an ermine robe, but with a symbolic cake melting in the background. The king is watching Kylian Mbappé celebrating France’s 2018 World Cup victory on television. Criticism of the monarchy seems clear, but are we to see celebrity footballers as a replacement for royalty? The work asks the question but doesn’t answer it. Think about that, it seems to say.

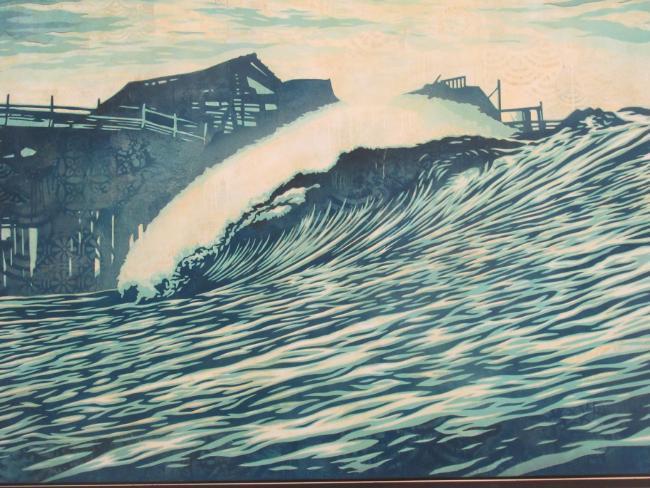

Hokusai inspired street art. Photo: Marian Jones

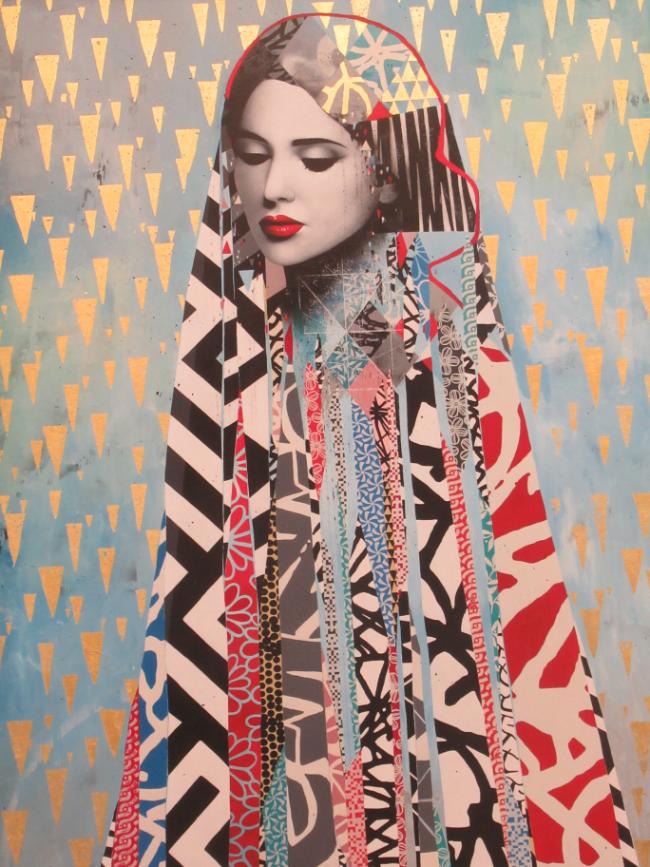

Suddenly, there’s a change in tone. The final room is labelled Le Salon, and inside the walls are packed with examples of street art, all jostling for space and attention. It’s a glorious jumble of different media (collage, screen prints, engravings) and colors (black and white, fluorescent, golden). Ideas are jumping around in all directions. I experience intrigue here, humor there, moments of incomprehension and some of recognition. For amid the clashing styles and images there’s a Hokusai look-alike, a modern take on a Greek sea goddess, a Japanese couple in traditional dress acting out Klimt’s The Kiss, and, I imagine, other references which I have not spotted.

Klimt inspired street art. Photo: Marian Jones

The design of Le Salon is no accident. As Annick Lemoine explains, crowding the art in like this is “reminiscent of the way artworks were exhibited in 19th-century salons.” Specifically, it’s a reference to the Salon des Refusés of 1863 where artists who’d been rejected by the Académie des Beaux Arts despite – as the information displayed here puts it – “their talent and their audacity,” clubbed together to put on their own exhibition. Some of them, including Monet, Cézanne and Pissarro, went on to gain huge and lasting public recognition. Just as Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe shocked visitors at the 1863 Salon, but proved a harbinger of things which followed, much of today’s urban art breaks new boundaries and some of it will surely influence what comes next.

And yet, some questions remain. Street art is often improvised and impermanent, yet here it is given a place in one of the city’s most prestigious institutions. Does that make it, ironically, too “establishment”? You could ask the same question when, as recently, a Banksy piece sells for 25 million dollars. Yes, the art here has “made it” in one sense, but new, often rebellious, pieces are still popping up all over the suburbs. And what about those who shudder to see spray-painting anywhere near classical works? I wouldn’t want to see these pieces move in permanently, sending the message that artworks from the past can no longer command an audience. But I can also see that this exhibition will draw in people who might not otherwise visit an “elite” gallery and that’s surely a good thing.

The spray can had a last message for me as I passed it again on my way out. “We are the unexpected, the uninvited, the overlooked, the unseen” ran the text, before explaining that “now is the time to emerge, to transform the transient into the timeless, to elevate the overlooked and to step into the light and take our place. We are here.” Yes, I thought, and why not? Bravo to the Petit Palais for this innovative experiment.

DETAILS

We are Here: An Exploration of Street Art at the Petit Palais

Avenue Winston Churchill, Paris

Nearest metro: Champs-Élysées Clémenceau

Until January 19th, 2025

Entry Free

Tuesday to Sunday from 10 a.m. – 6 pm

Late openings until 8 pm on Fridays and Saturdays

Spray can. Photo: Marian Jones

Lead photo credit : Petit Palais. Photo: Marian Jones

More in invader, Museum, Petit Palais, Seth, Shepard Fairey, street art

REPLY

REPLY