Paris Green: The Paint Pigment Packed with Poison

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

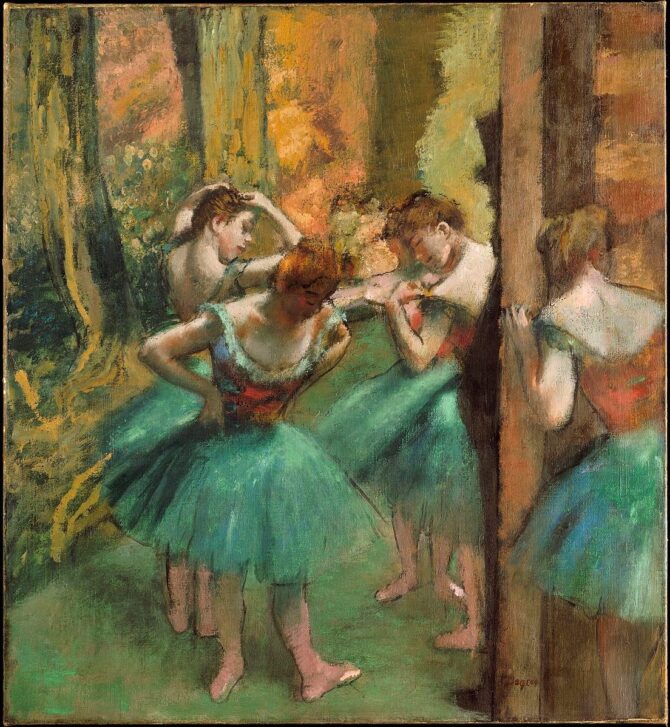

Green, one of the coolest, calmest colors, was once a dangerous pigment. A shade of green known as Paris Green contained deadly levels of arsenic. The vibrant color popular during the 1800s contributed to the downfall of artists and artisans, dressmakers and former heads of state. Paris Green morphed from a pigment into a poison.

Though abundant in nature, green is a very tricky color to replicate. Green pigments in antiquity like those found in tomb paintings in Ancient Egypt and at Pompeii were made of powdered malachite and verdigris. Prior to the 1780s, fashionable furnishings and clothes could be tinted green but no green dye existed. Fabric was dipped into a vat of blue dye followed by a dip into a vat of yellow. The resulting color quickly faded into a somber shade.

Carl Wilhelm Scheele in 1780. Public domain

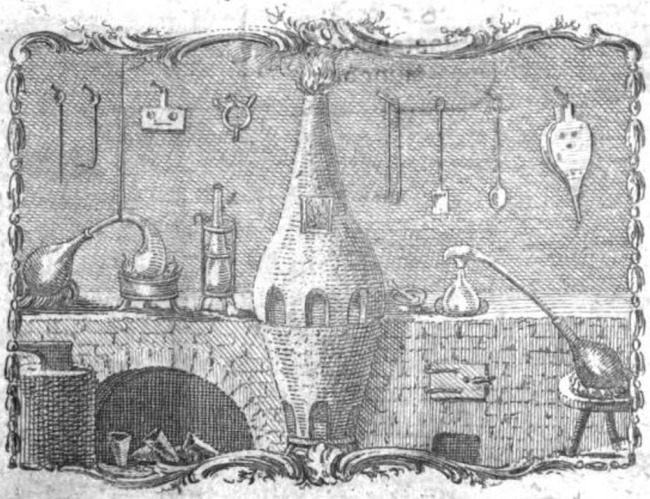

So imagine the thrill of Wilhelm Scheele’s invention in 1775 – a new light green with a luminous glow. From his workbench of colored vials and burbling pots, the skilled Swedish-German chemist created a compound of copper arsenite. He knew he’d hit on something lucrative, but he was well aware his new pigment could be poisonous. But everything has its price, and these dangers were brushed aside by the manufacturers of synthetic dyes concerned only with the commercial possibilities. Scheele’s Green should have been marked with a skull and crossbones. He died at 43 from inhaling the fumes from his own experiments.

As Scheele’s Green had the tendency to take on a lime-like tinge, the pigment was chemically tweaked in 1814, to provide a deeper, lasting emerald color with more blue undertones. This durable color was marketed under many names, one of which was Paris Green.

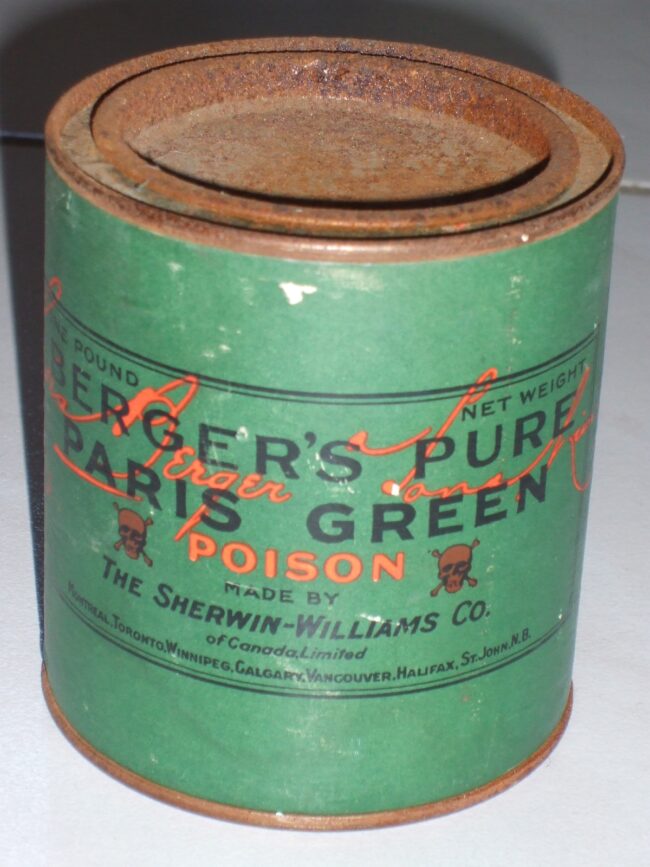

Can of Paris green pigment by Sherwin-Williams Co. Wikimedia commons

France at this time was concerned with the urbanization of its society. It was thought that city living would sap the nation’s strength. Green villages had been swapped for Paris streets of an ugly, urban grey. The color green became linked to health, and Parisians in the Romantic Era yearned to return to a fresh, pastoral life. Therefore, Paris Green enjoyed instant popularity. The crystalline pigment was instantly adapted for use in candies and puddings, wallpaper, paint, toys, book covers, postage stamps, ink, fabric and clothing.

Paris Green found its way in to the armoires of fashionable French women, lured by the shimmer of the new emerald-colored dresses. These fashion victims, garbed in green, became ill; those creating their fashions even more so.

Engraving on the title page of Scheele’s Chemical Treatise on Air and Fire (1777). Wikimedia commons

Superstition holds that dressmakers and tailors didn’t like working with green and considered the color unlucky. This folklore has basis in fact. Seamstresses and milliners who handled Paris Green began suffering from hideous blisters and lesions, stomach pain, even heart disease and cancer. The colored fabric often made the wearer and the worker ill through touch alone. Unlike dye, arsenical greens were an insoluble pigment, applied in a paste, and these party dresses would not be regularly laundered, if at all.

As part of the return to nature in the mid 19th century, women thought it alluring to wear wreaths of fragrant flowers entwined in their hair. Even Queen Victoria was depicted by Winterhalter with such a garland. Real flowers faded, so factories creating imitations were established. Paris Green was used in the creation of the fake foliage and as a finishing touch, the powdered pigment was blown onto the completed product. Apart from sores on their fingers, these artificial bouquets made the flower makers nauseous and gave them pounding headaches.

Franz Xaver Winterhalter, Portrait of Queen Victoria, 1847. Royal Collection UK. Public domain

In 1859, Emperor Napoleon III’s physician, Dr. Ange-Gabriel Maxime Vernois, connected the symptoms with the color and conducted inquiries into the occupational hazards of flower making. The ill flower makers were being slowly destroyed by their contact with Paris Green. The toxic green dust, he realized, could be inhaled or eaten off dirty fingers. Vernois noted that in a time when most factories and workshops were overrun by rats and vermin, there were none to be seen.

The doctor focused on the male workers called apprêteurs d’etoffe who brushed an emerald Paris Green paste directly onto cloth with uncovered hands and forearms. At bathroom breaks the arsenic on their hands affected their genitals, creating lesions which were often mistaken for syphilis. Medical illustrations from the time are vivid and frightening.

Gown in Paris Green. Photo: Palais Galliera

In 1863, probably under Dr. Vernois’ orders, the fashionable Empress Eugenie wore an emerald green gown to the Opera, colored with a new non-toxic dye known as vert Guignet or viridian. Yet French artists persevered by using not only viridian, but the dangerous Paris Green on their palettes. Excited by the intense pure green and its ability to make nature come to life, it was one of their most popular pigments. Tellingly, as early as 1867, Paris Green was marketed as the world’s first insecticide.

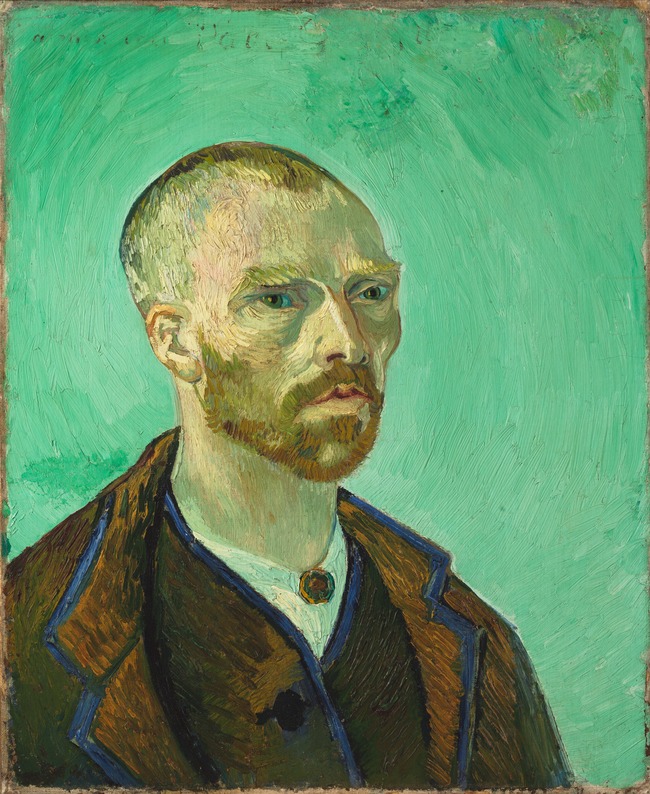

However, it was readily accepted by Manet, the French Impressionists and the Post Impressionists, believing if they did not eat or drink it, they were safe from its effects. They would have absorbed the poison through their skin, by holding their brushes in their mouths and eating off their painty fingers. Van Gogh is rumored to have licked his brushes. It could have been a brush with death. In van Gogh’s, Self-Portrait (Dedicated to Paul Gauguin) 1888, the lurid background is Paris Green.

Van Gogh, self-portrait dedicated to Gauguin, September, 1888. Public domain

Putting two and two together, researchers theorized that arsenic in Paris Green might have contributed to Van Gogh’s mental instability and chronic stomach pain. It’s possible that Paul Cézanne’s severe diabetes was one of many symptoms of arsenic poisoning, and toxic Paris Green may have caused Claude Monet to go blind. When Monet was asked what pigments he used, he rang off a colorful list that deemed his palette mainly toxic. He used Paris Green among other green pigments in his famous 1869 Bathers at la Grenouillère.

Claude Monet, Bathers at La Grenouillère, 1869. The National Gallery London. Public domain

Édouard Manet’s Music in the Tuileries (1862) contains both Scheele’s and Paris Greens. Manet died a painful death from syphilis at age 51. For the reason that Dr. Vernois found that male colorers contracted syphilis-like symptoms, perhaps one could theorize that Manet succumbed to the same. However, it is medically agreed upon that the painter died from venereal disease.

Could arsenic-laced paint be the reason for Renoir’s debilitating arthritis? Perhaps all these above ailments were exacerbated by the over-indulgence in the other so-called green poison: absinthe.

Green candles were killing people. Children attending a Christmas party where dyed green candles burned were fatally poisoned. Nineteenth-century journals contained reports that children sleeping in bright green rooms were “wasting away.”

Édouard Manet, Music in the Tuileries, 1862, Hugh Lane Gallery, Dublin. Public domain

Understandably, as the Romantic trend to green became more popular, it was fashionable to decorate one’s parlor or bedroom with wallpaper tinted with Paris Green. The arsenic-laden pigment degraded with moisture into a toxic arsene gas. Napoleon’s apartments at Fontainebleau confirm the Emperor’s love of brilliant green furnishings. His bed was draped by his color of choice.

During Napoleon’s exile in Saint Helena, he often wrote that he was being murdered by his British keepers. The symptoms that the weakened Napoleon reported prompted this speculation – he suffered from swollen legs, abdominal pain, jaundice, and vomiting. When the Emperor’s exhumed body was shipped back to France 19 years after his death, his corpse showed little decomposition; its preserved state indicated arsenic was in his system. But who was poisoning him in this isolated outpost 1200 miles from anywhere? It was most likely Napoleon’s environment that did him in.

Though much research has gone into this theory, no one’s about to open up Napoleon’s porphyry crypt at Les Invalides. However, a good clue exists – his hair. Arsenic lingers in the hair and Napoleon frequently bequeathed locks of his hair to his family and friends. He must have had his hair cut frequently, because even I, before the internet, let alone Instagram, have held a Ziploc bag containing a reddish lock of Napoleon’s hair.

Analysis showed arsenic levels 100 times higher than in earlier snipped samples. Scientist Dr. David Jones determined that Napoleon had been suffering from chronic arsenic poisoning from the Paris Green (probably at that time, Scheele’s Green) in his surroundings. His wallpaper was killing him.

From 1815 to 1821 during his exile on St Helena Island, Napoleon Bonaparte lived at Longwood House. Today the building is a museum owned by the French government. Photo: David Stanley / Wikimedia commons

Through an almost unbelievable coincidence, Dr. Jones found a sample of wallpaper from Longwood House, Napoleon’s exile on St. Helena. In a scrapbook owned by a woman in Norfolk, England, was a swatch with the handwritten caption: This small piece of paper was taken off the wall of the room in which the spirit of Napoleon returned to God who gave it. AKA – his deathbed. The faded wallpaper did indeed contain arsenic. When damp or moldy, it off-gassed poisonous, arsenic-laden vapors. Napoleon’s already fragile health made him more susceptible to the miasma of arsenic in his quarters. To this day Longwood House shows the greens Napoleon would have lived with. The bright billiard room and the curtains surrounding Napoleon’s narrow camp bed are still green. A replica of the poisonous wallpaper is adhered to the walls.

In the 1960s, the formulation of arsenic originally found in Paris Green was banned outright. Ironically, 21st-century green can’t be eco-friendly. The recognizable symbol of sustainability is damaging to the environment. Commercial green pigments are still a noxious mix of chemicals that can’t be safely recycled or composted. Like the citizens of the 19th century, we can’t shake the long tail of poisonous Paris Green.

Use of Paris Green as insecticide, poster issued by US Public Health Service. Public domain

Lead photo credit : Edgar Degas, Dancers Pink and Green, 1890. The Met.

More in arsenic, Claude Monet, Napoleon, Paris Green, Vincent van Gogh

REPLY

REPLY