Liberty Led the People at the Paris Olympics

Did you notice that one of France’s most iconic works of art – Liberty Leading the People by Eugène Delacroix – popped up all over the Olympics and Paralympics? From the two opening ceremonies to the mascots in evidence all over Paris, references were repeated. It can be no coincidence that a team of experts from the Louvre had spent six months restoring the work and ensuring it was returned to the gallery earlier in the summer, in good time for the Games. Its revolutionary message was a key part of the image the country wanted prominently on show while the world was watching.

The recreation of the painting by actors at the Conciergerie was one of the standout moments of the Paris Olympics Opening Ceremony. Who didn’t feel uplifted by their spirited rendering of “Do you Hear the People Sing?” from Les Misérables? At the second opening ceremony, Andrew Parsons, president of the International Paralympic Committee, spoke movingly of the “inclusion revolution” he hoped these games would unleash. Seeing what the Paralympic athletes achieved, he said, should inspire the advance of disability inclusion everywhere, “whether on the field of play, in the classroom, concert hall or in the boardroom.” Let’s do it the French way, he implied, for nothing less than a revolution will do.

The setting for his words, the Place de la Concorde, is inextricably linked to the revolution of 1789. The Delacroix painting, although referencing later events in the 19th century, is recognized worldwide for its depiction of the revolutionary spirit for which France is famed. And the picture’s central figure of Marianne, musket in one hand and tricolore in the other, rising up defiantly over a pile of dead bodies to lead men into battle, is surely everyone’s go-to image of triumphant revolution. She is the embodiment of liberty, shown in profile like a classical goddess and wearing the red phrygian – or “liberty” – cap favored by the insurgents of 1789. It was, of course, the model for the Phyrges, the official mascot for Paris 2024.

The painting’s impact is heightened by its size – it measures 8.5ft x 10.5 feet – and by the carefully chosen group of other figures who represent “the people.” To the left, a top-hatted man has rushed to join the fray with his hunting rifle, alongside a worker waving a sabre, while behind them surges a teeming crowd, all armed with whatever came to hand. The young boy on Marianne’s other side, waving two pistols – perhaps firing one of them – and the revolutionary at her feet, wearing splashes of patriotic red, white and blue, confirm the message. The people, old and young, from many different backgrounds, will rise up. They will prevail.

The message is so powerful that it hardly matters that the history the picture recounts is not clear to many modern viewers. It is not, as is often thought, a scene from 1789, but from a later revolution in 1830, when the restored Bourbon King Charles X was forced by a popular uprising to abdicate. Delacroix himself had witnessed the violent protests of three days in July 1830 when fury at new restrictive laws being introduced led to barricades in the streets and fierce fighting against royal troops. Some 500 insurgents were killed, but Charles fled the country and was replaced by the so-called “Citizen King,” Louis-Philippe who created a constitutional monarchy. It wasn’t a total triumph, but it was a step on the way to the end of the Bourbon monarchy 18 years later, when Louis-Philippe was also forced to abdicate.

Portrait of King Charles X. Around 1825. by François Gérard. Musée Carnavalet, Histoire de Paris

The painting, completed by Delacroix in three months, had a checkered early history. It attracted large crowds when it was exhibited at the Salon of 1831, but criticism was mixed. Some found it heroic, others distasteful. The government bought it for 3,000 francs, intending, it is said, to hang it in the Throne Room at the Palais du Luxembourg, perhaps to serve as a warning to the king about the power of revolution. But soon it was removed, presumably because it was deemed too inflammatory, and given back to Delacroix. Over 20 years later, the artist chose to include it in one of his exhibitions, thus returning it to the public eye and in 1874 it was acquired by the Louvre.

The Louvre Palace. Photo Credit: Ali Sabbagh/ Wikimedia Commons

The question of Delacroix’s own attitude to revolution is an interesting one. He was dependent on commissions, including from royalty, and is thought to have been a spectator, rather than a participant at the unrest of July 1830 which inspired the painting. Art historians have noted that when the work re-appeared in public in the 1850s, the bright red of the phrygian caps had been toned down.Perhaps the artist, who was certainly an establishment figure during the reign of Louis-Philippe and in Napoleon III’s Second Empire, felt obliged to make his message a little less strident? However, a letter he wrote to his brother about the work may indicate his true feelings: “I may not have fought for my country, but at least I shall have painted for her.”

Whatever Delacroix himself thought about revolution, his Liberty Leading the People has taken on a life of its own and its message is unequivocal. Revolt can be justified, it says. Collective action can be unstoppable. The painting is recognized worldwide and although people may disagree over which causes are justified, all can concur that some things are worth fighting for. It was deemed so important to highlight this painting during Paris 2024 that it was given a major facelift in preparation. Restorers spent six months on the project, removing the eight layers of varnish which had accumulated in previous attempts to brighten the colors. The result is a fresh and impactful.

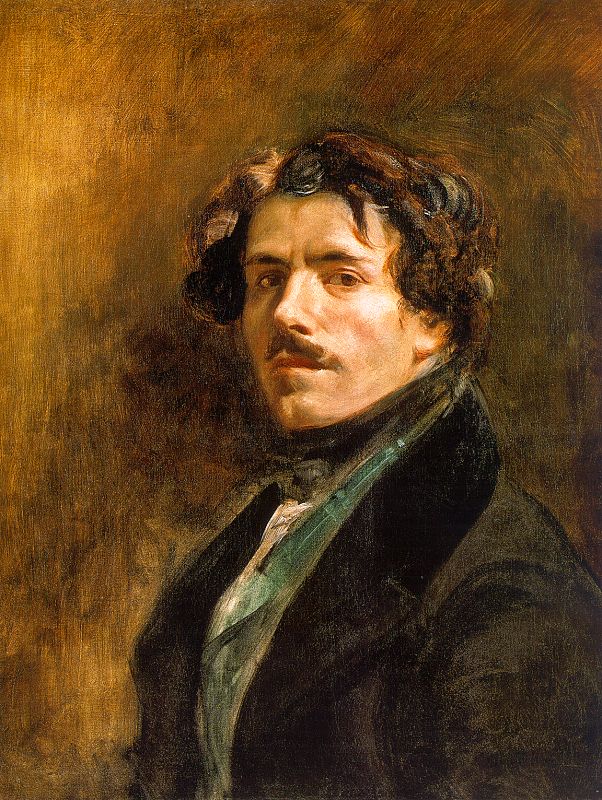

Eugène Delacroix, Self-Portrait, 1837 Oil on canvas, 65 x 54 cm, Louvre –Public Domain

In the two centuries since Delacroix completed Liberty, which must be the Louvre’s second most recognized painting after the Mona Lisa, its image has been referenced and adapted many times in the name of a multitude of causes, both in France and abroad. The sculptor Bartholdi is known to have taken inspiration from it for his Liberty Enlightening the World, better known as the Statue of Liberty in New York City. It was given to the United States as a gift from France, a celebration of America’s centennial of independence and of both country’s commitment to freedom and democracy.

Victor Hugo must surely have had the painting in mind when writing Les Misérables. It certainly features the revolution of 1832 and perhaps it was Delacroix’s depiction of the young boy waving pistols which inspired the character of Gavroche? In 1944, when the German occupation ended, Marianne’s image appeared on banknotes and stamps to underline the return of an independent French government.

A Marianne-like figure in depictions of the “Yellow Vest” movement. Image via Pascal Boyart’s website

Artists and protesters from around the world have re-interpreted Liberty Leading the People for their own causes. The British rock band Coldplay adapted it for the cover of their album Viva la Vida and more recently the street artist Pascal Boyart has painted a Marianne-like figure into his depictions of the “Yellow Vest” protests which have taken place all over France. Versions have appeared at protests as far apart as Bulgaria, Hong Kong and Israel, where a Marianne-inspired figure, raising a Palestinian flag, was painted onto the West Bank Wall. More examples can be seen currently in Paris, for example in Rue Le Boucher in the 4th arrondissement, where a mural captioned Vive la Résistance Ukrainienne, shows Marianne holding a blue and yellow flag aloft.

“Liberty Leading the People” Ukraine mural in Paris. Photo: Marian Jones

The Paris Olympics and Paralympics will leave countless images of sporting triumph, of stunning Parisian vistas and surely also of Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People. The Games have finished and the Phrygian mascots have been taken to the four corners of the globe, but the image of Marianne will linger long in the mind. She made a wonderful advocate for Paris 2024, for she represents a call to triumph in spite of adversity and nothing could be more Olympian. Or indeed more French.

Additional Information

The newly restored Liberty Leading the People can be seen on Level 1 of the Denon Wing at the Louvre (Room 700)

Louvre Opening Times

Monday, Thursday, Saturday, Sunday 9 am – 6 pm

Wednesday and Friday 9 am – 9 pm

Tuesday closed

Lead photo credit : La_Liberté_guidant_le_peuple_-_Eugène_Delacroix_-_Musée_du_Louvre, Photo: Shonagon/Wikimedia Commons

More in Eugène Delacroix, French Art, history, Olympics, Paris Olympics