Get to Know Gustave Caillebotte Better at the Musée d’Orsay

I’ve long been intrigued by the artist Gustave Caillebotte, mainly because his Paris Street: Rainy Day is so arresting. It was a big hit at the Impressionist exhibition of 1877, alongside Renoir’s Bal du Moulin de la Galette and Monet’s La Gare Saint-Lazare and its curiously modern depiction of a couple, arm in arm under an umbrella, making their way along a drizzly boulevard has been a key image of Paris ever since.

It’s currently visiting Paris, on loan to the Musée d’Orsay from the Art Institute of Chicago and I went along to the exhibition, Caillebotte Painting Men, where it’s playing a star role. This title poses a question I had not considered. Did Caillebotte paint mainly masculine figures? The museum’s website notes explain that he “took his subjects from his surroundings (Haussmann’s Paris, the country houses around the capital), his male acquaintances (his brothers, the workers employed by his family, his boating friends), and ultimately from his own life.” So, this would be a chance to find out much more about a man who was a key figure during one of the most exciting eras in French art – the late 19th century – and yet who is less familiar to us than some of his contemporaries.

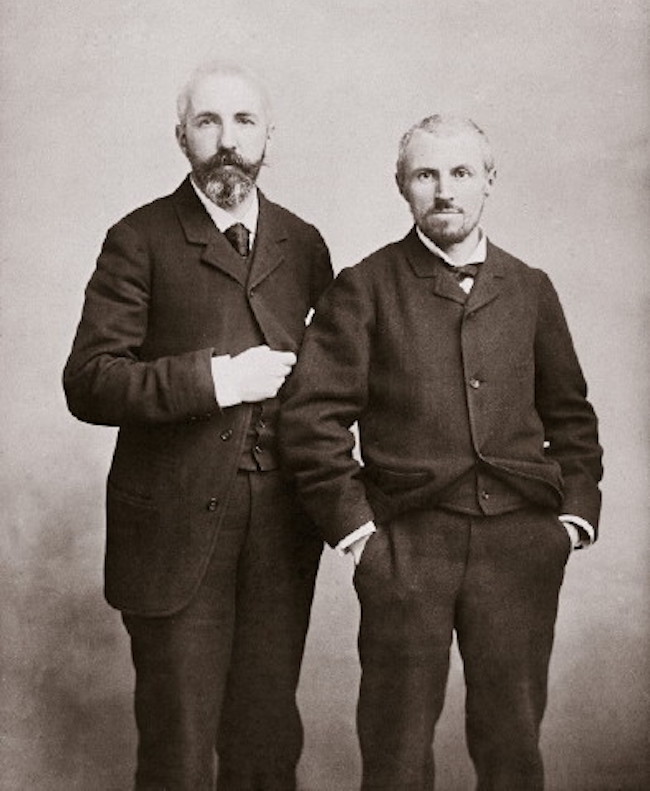

Gustave Caillebotte (right) and his brother, Martial. Author unknown, Wikipedia. Public domain

The exhibition, which runs until January 19th, 2025 and marks the 130th anniversary of Caillebotte’s death, brings together his most important paintings alongside lesser-known works and sketches, documents and photographs which shed light on the artist, his themes and the way he worked. It opens with works which set him in context in his everyday environment. This well-off young bachelor, who had family money behind him, had abandoned his study of law to enroll at the École des Beaux Arts. Luncheon, which he painted in 1876 when he was in his early 30s, illustrates his comfortable existence, living with his widowed mother and two brothers in a Haussmannian appartment in the fashionable 8th arrondissement.

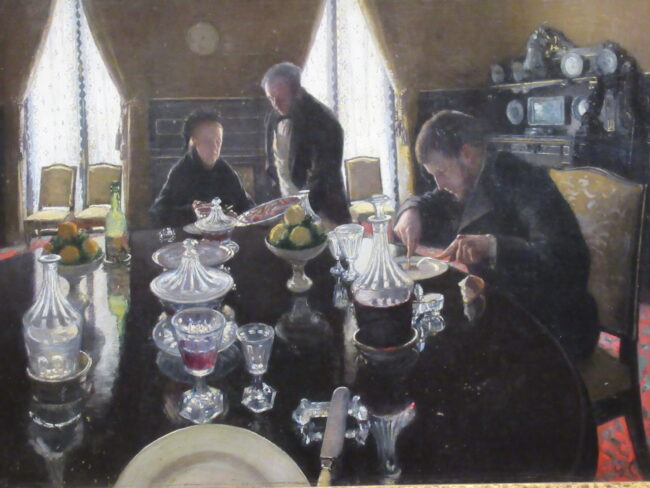

Luncheon, by Gustave Caillebotte. Photo at the Orsay exhibition by Marian Jones

Family figures, dressed formally in black, sit at an expensively laid table, surrounded by dark, heavy furniture and are waited on by the family butler. There doesn’t seem to be much conversation, but these look like people whose lives are solid and predictable. A second work, Young Man at His Window, shows his brother René staring down at the street from the first floor. The mood is unclear. Is he confidently surveying the road as a landlord of several surrounding properties? Or is he gazing wistfully at the outside world, from which he feels remote? A nearby panel adds the information that René, only 25, died just a few months later and that “his gambling debts …. and his involvement in a duel fuelled speculation that he had committed suicide.” Caillebotte’s solid, bourgeois existence was also tinged by tragedy.

The artist’s younger brother in the home on rue de Miromesnil (1875). By Gustave Caillebotte

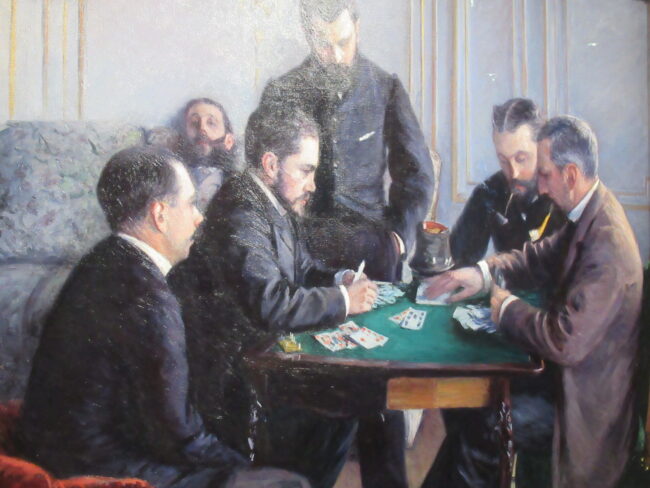

Caillebotte captured indoor scenes which reflected his everyday life, the hours of leisure he spent with similarly well-off companions. His distant cousin Eugène Dufresne is shown reading a novel, Partie de Bézigue portrays a group of men playing one of the fashionable card games from the time. Four men sit at a table, contemplating their cards, one stands looking on, hands in pockets, and another dozes on a sofa behind them. The atmosphere is one of camaraderie and also of indolence, of time to while away. Such intimate domestic scenes were more usually painted by the female artists of the day, including Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassat.

Partie de Bézigue, Gustave Caillebotte. Photo at the Orsay exhibition by Marian Jones

Caillebotte’s outdoor paintings often reflect the “other” half of his daily life, the time he regularly spent in the countryside, particularly in the family house at Yerres, just outside Paris. His Chemin Montant shows a fashionably dressed couple strolling along a country path, and is painted more in the style of other Impressionist artists. Splashes of bright color are set against the surrounding greenery, and we see the play of light between the leaves on the trees and the shadows they make on the ground. His Vegetable Garden at Gennevilliers is another Impressionist treatment of a rural scene.

Chemin Montant, by Gustave Caillebotte. Photo at the Orsay exhibition by Marian Jones

Caillebotte in his greenhouse (February 1892), Petit Gennevilliers. Author unknown, Wikipedia commons

Works which have been loaned by U.S. galleries in Milwaukee and Virginia are grouped with the Orsay’s own Baigneurs (Bathers) and newly acquired Partie de Bateau (Boating Party), offering delightful glimpses into scenes of men messing about on rivers. It was a familiar topic for Caillebotte, who was a member of a local boating club, and he captures the leisurely enjoyment of the rowers and the light playing on the water’s surface in Perissoires (Canoes). He portrays other riverside moments in works like Canotiers which gives us a close-up view right inside the boat where two men are heaving their oars. The light-hearted Baigneurs, in which a figure in a striped bathing suit is poised to dive in, is another memorable work.

Baigneurs, by Gustave Cailebotte. Photo taken at the Orsay exhibition by Marian Jones

As these works show, Caillebotte’s social circle tended towards the masculine and he was also the first artist to paint pictures of working men. His Raboteurs (The Floor Scrapers) caused a real stir when first shown at the Impressionist Exhibition of 1876. The portrayal of workmen, stripped to the waist and engaged in back-breaking labor, was startlingly new. He had made many preliminary sketches – some of them displayed here – in his determination to capture a realistic view of the men at work. While some critics found the subject matter “vulgar,” others saw in it the artist’s admiration for these muscly laborers, men whose lives were so different from his own. Similarly, his House Painters casts an interested eye on an “ordinary” moment in the lives of two painters assessing a shop front, giving them and their work a quiet dignity.

Les Raboteurs de parquet “The floor scrapers” (1875), Gustave Caillebotte, Paris, musée d’Orsay.

More controversial is the small selection of nude or semi-nude paintings including Man at his Bath, showing a naked man with his back to us toweling himself dry and Man Drying his Leg, another intimate bathroom scene. Do they, some have wondered, reveal Caillebotte’s particular interest in the male body and does that tell us something new about his sexuality? The curator, Paul Perrin, thinks not, arguing that painting a handsome man does not mean that “one necessarily feels desire for him.”

It must be noted that between these two paintings hangs Nude on a Couch, an even more explicit painting of a completely naked woman reclining on a sofa. We also know that Caillebotte lived with a female companion, Charlotte Berthier, for a number of years. He may, or may not have been gay, but we cannot be sure. Anyway, say some critics, is it important to know that? Surely the works should just speak for themselves. As one reviewer put it: “It seems incumbent on museum curators to confect a thesis for every exhibition.” But here we could simply focus on this show as a once-in-a-generation chance to see most of Caillebotte’s best work in one place.

Man Drying His Leg, Gustave Caillebotte. Photo taken at the Orsay exhibit by Marian Jones

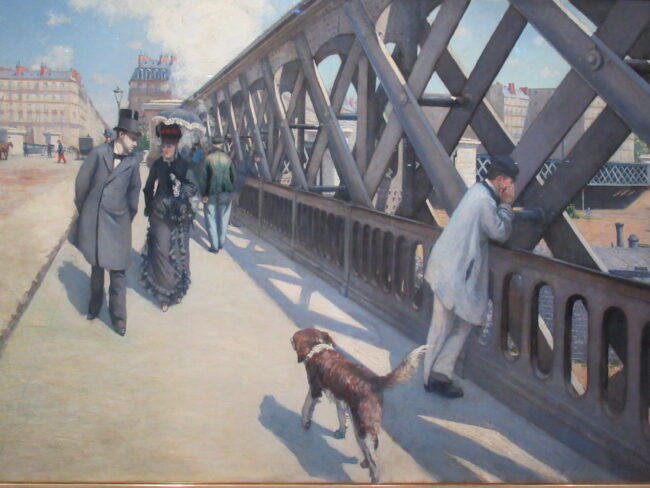

And ultimately, it was the chance to see Caillebotte’s “blockbusters” which I enjoyed most. In addition to The Floor Scrapers and the House Painters, there is Le Pont de l’Europe, his magnificent tribute to the colossal feat of engineering which was the city’s new railway bridge, a painting also enigmatic in its portrayal of the figures passing by. Are the man and woman together? What is the worker on the right thinking as he gazes over the parapet? Why did Caillebotte include a passing dog so prominently and did he, as some think, paint himself into the picture? The star attraction is surely his Paris Street, Rainy Day, the largest of all his works and the one which first made his name at the exhibition in 1877.

Gustave Caillebotte was a well-known art collector, buying up the works of other impoverished artists and promoting the impressionist movement selflessly. Notice, for instance, how a Renoir painting forms the backdrop to his own Self-portrait at the Easel. On his death in 1894, he bequeathed his outstanding collection of Impressionist paintings to the French government and alongside this exhibition, the Musée d’Orsay is showing the entire bequest in one of its permanent galleries. The 80 pieces on display include paintings by Manet, Cézanne, Degas, Pissarro and Monet, plus one of Caillebotte’s earliest and favorite purchases, Renoir’s Bal du Moulin de la Galette.

Le Pont de l’Europe, Gustave Caillebotte, photo taken at the Orsay exhibit by Marian Jones

Endearingly – and regrettably – Caillebotte was too modest to include any of his own works in the collection he left to the nation. The result was that they were sold off and are now scattered in galleries on both sides of the Atlantic. Perhaps that is one reason why he attracts less attention that some of his contemporaries. This exhibition, which brings so many of his paintings, including all the favorites, back under one roof, is an unmissable opportunity to get to know him and his work a little better. Do go if you have the chance.

DETAILS

Caillebotte Painting Men

Musée d’Orsay until January 19th, 2025

Opening times and days (Closed Mondays)

Full price ticket is €16. Concessions: €13

Canotiers, Gustave Caillebotte. Photo taken at the Orsay exhibit by Marian Jones

Lead photo credit : Gustave Caillebotte, "Paris Street, Rainy Day", 1877, Art Institute of Chicago, Charles H. and Mary F. S. Worcester Collection

More in Gustave Caillebotte, Musée d’Orsay

REPLY