Degas at the Opera in Paris and Washington D.C.

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

The year 2019 marked the 350 anniversary of the National Paris Opera, founded as a royal institution in 1669, part of the Académie de Poésie et Musique under Louis XIV. The 17th century poet Pierre Perrin founded this major French cultural institution, but shortly after its launch composer Jean-Baptiste Lully took over and changed the name to the Académie royale de la Musique in 1672. After the French Revolution changed the name to the Opéra Nationale, the Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte decided on the Académie Impériale de la Musique in 1804. Then his nephew Napoleon III (1808-1873, president and then emperor 1841-1870) changed the name in 1848 to the Opéra-Théâtre de la National and then again, in 1854, to the Théâtre Impérial d’Opéra. Under Napoleon III, the Garnier Opera House came into existence in 1875, which we associate with the musical Phantom of the Opéra. In 1990, the Opéra Batille (Opéra de Paris) became the major venue, while the Palais Garnier continues to host performances of the Paris Ballet.

Théâtre de l’Académie royale de Musique, known as the Salle Le Peletier, on the rue Le Peletier (1821-1873). Print engraving, c 1821. Source: Public Domain (Wikipedia)

August Lauré (1818-1900), Théâtre de l’Académie royale de Musique, Grande Salle, 1864

Source: Public Domain (Wikipedia)

However, during the youth of French artist Edgar Degas, the Opéra Le Peletier, located in the Salle Le Peletier, reigned supreme. Built in 1821, it burned down in 1873. Hence, we learn immediately while touring the exhibition Degas at the Opera, the Musée d’Orsay’s lavish contribution to the Paris Opera’s landmark birthday celebration, that these paintings, drawings, prints, and sculptures come from Degas’ imagination based on his memory of the ballet performances at the Salle Le Peletier.

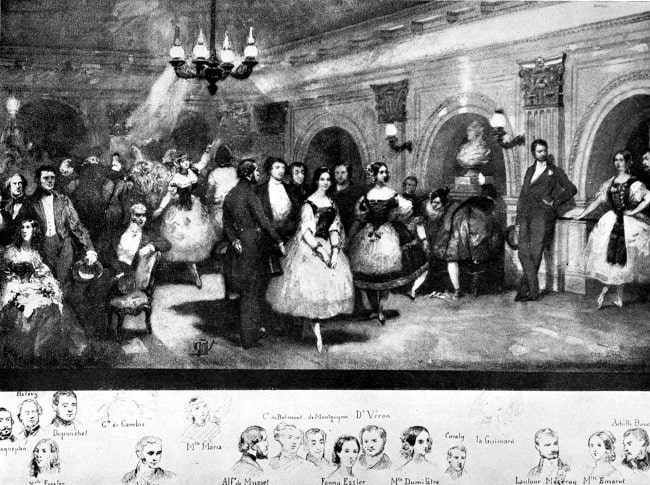

Eigene Lami, Le Foyer de la Dance, Salle Le Peletier, 1841, lithograph. Source: Public Domain (Wikipedia)

In a lithograph of the Salle Le Peletier, the artist offers portraits of the principle dancers and male patrons of the ballet, such as Ludovic Halévy, Alfred de Musset, and renowned dandy Charles Lautour-Mézéray, whose loge at the opera became the hotspot for society’s sexy flirtations. Degas’s characterization of ballerinas with beaux seems to imply a shadier meaning, introducing backstage sugardaddies who seem to lounge in the wings watching their “girls.”

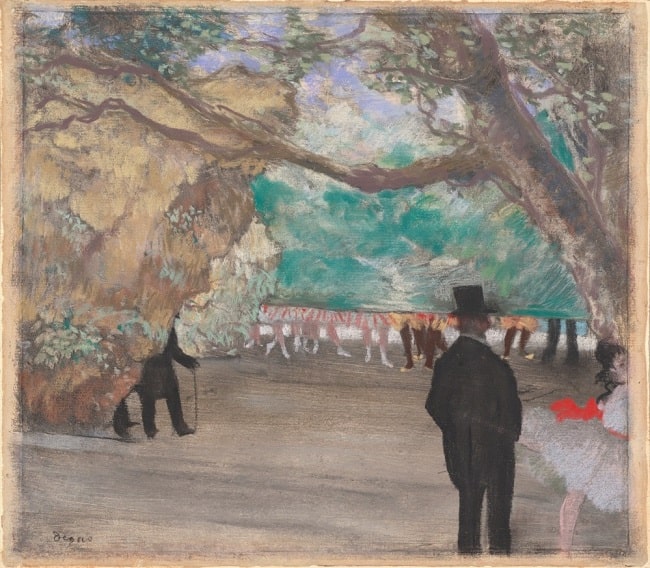

Edgar Degas, The Curtain, 1880, pastel over charcoal and monotype on laid paper,

sheet: 29 x 33.3 cm (11/ 7/16 x 13 1/8 inches) National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon

This sordid side of the opulent Paris Opera may be one way to analyze these 200 examples of Degas’ 1500 Paris Opera images. However, to my eyes, Degas at the Opera enhances the study of this particular artist’s prodigious study of women’s bodies. Degas explored the female body in motion and at rest in various situations. Here we see his famous ballet dancers. He also drew and painted laundresses, milliners, acrobats, cabaret singers, and socialites. His earliest paintings from 1857 carefully describe Italian women in so-called “peasant” dress. His late sculptures made of wax depict female nudes posing in ballet positions and in the midst of their bathing routines. These wax figures were cast in bronze after his death in 1917.

Edgar Degas, Portrait of Mlle Fiocre in the Ballet “La Source,” ca. 1867-1868, oil on canvas, overall: 130 x 144 cm (51 3/16 x 56 11/16 inches), framed: 160 x 175.3 x 15.9 cm (63 x 69 x 6 ¼ inches), Brooklyn Museum, Gift of James H. Post, A. Augustus Healy, and John T. Underwood

Degas’ ballet works began in 1867 with the Portrait of Mlle Fiocre in the Ballet “La Source,” ca. 1867-1868, and continued through to his late sculptures circa 1910-11. We believe that he ceased to create any art in 1912. Therefore, we learn in this exhibition that ballet inspired Degas most of his life and his ambivalent obsession with women remains cloaked in mystery, regardless of all the nasty comments still on record that lead us to believe he simply hated women.

Edgar Degas, The Ballet Class, 1873, oil on canvas, over all: 85.5 x 75 cm (33 11/16 x 29 ½ inches), Musée d’Orsay, Bequest of Isaac de Camondo, 1911

My intuition believes that Degas masked his true feelings. His interpretations of various women’s bodies intensified his commitment to Realism, his concept of Realism, which, he felt, revealed unvarnished truths about human existence through depicting ordinary human behavior. Nevertheless, Degas’ gaze was not compassionate, but instead highly judgmental. Often he launched cruel insults indiscriminately and was called out for his bad behavior. Degas never learned. He couldn’t understand why speaking honestly should come between friends. As a young artist, Degas created psychologically revealing scenes, such as his aunt’s troubled marriage in The Bellelli Family, 1858-67, on view at the Musée d’Orsay. However, as his poor eyesight continued to diminish, Degas ceased to scrutinize faces, preferring poses that convey psychological content. In this respect, the act of painting, drawing and sculpting women’s bodies fulfilled a need, perhaps even soothed his secret pain. One wonders if Degas ever felt loved. As far as we know, he never committed to any long term romantic relationships (clandestine or otherwise), convinced, he would explain, that a conventional marriage did not suit his lifestyle.

Edgar Degas, The Ballet Class, 1874, oil on canvas, 83.5 x 77.2 cm (32 7/8 x 30 3/8 inches),

Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Mrs. Harry Payne Bingham, 1986 [not in the exhibition]. Source: Metropolitan Museum (Public Domain)

Edgar Degas, The Ballet Class, c. 1873, oil on canvas, overall: 47.63 x 62.23 cm (18 ¾ x 24 ½ inches), framed: 72.39 x 87.63 x 9.53 cm (28 ½ x 34 ½ x 3 ¾ inches); National Gallery of Art Washington, DC, Corcoran Collection (William A Clark Collection)

How do we know this? The life of a “petit rat” (student dancer) required the utmost discipline in order to succeed in the corps de ballet. Her family was very poor and her ability to dance brought food to their table, a roof over their heads. Most likely, she lived with a single mother. At first, she would arrive with her mother, sister, aunt or other chaperone. Then she would acquire a benefactor who would augment her income in exchange for her favors. The ballet master decided on her career with the company. Any infractions might end her income from both the ballet and off-stage associations.

Edgar Degas, Ballet Scene, c. 1907, pastel on greenish transparent tracing paper,

overall: 76.8 x 111.2 cm (30 ¼ x 43 ¾ inches), National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Chester Dale Collection

Pivoting from Degas’ commentary on the dancers’ social status, let us now appreciate his incomparable artistic prowess, for no artist invented such novel compositions, color combinations and figural poses before this visually-challenged artist came along. Indeed, the sheer pleasure of studying so many great Degas works in person requires celebration. Here are masterfully controlled contours electrified by shimmering strokes of paint or pastel. Surfaces radiate with innovative blends of lime greens, lemony yellows, turquoise blues, rose pinks, orange-reds, and red oranges. This interaction of colorful marks reminds us of Degas’ participation in the Impressionist movement, the rebels who called themselves the Anonymous Society of Painter, Sculptors and Engravers, a.k.a “The Independents.” Degas bristled at the critics’ popularization of the soubriquet “Impressionism.” That the exhibition curators seem to wrestle with his deviations from the usual light-hearted Impressionist fare lays bare the limited advantages of corralling artists into one coherent art label. Degas’ full mastery served first and foremost Degas’ agenda.

Edgar Degas, Before the Ballet, 1890 /1892, oil on canvas, overall: 40 x 88.9 cm (15 34 x 35 inches), framed: 59.7 x 109.8 x 8.2 cm (23 ½ x 43 ¼ x 3 ¼ inches), National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Widener Collection

Edgar Degas, The Dance Lesson, c. 1879, oil on canvas, overall: 38 x 88 cm (14 15/16 x 34 5/8 inches), framed: 59.7 x 108.3 x 5.1 cm (23 ½ x 42 5/8 x 2inches), National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon

Degas actively organized most of the Anonymous Society’s exhibitions from 1874 through 1886, and invented the rule that any members of their independent exhibitions who submitted work to the annual state-sponsored Salon would be barred from future participation in their independent shows. The rule didn’t stick. Yet it demonstrates Degas’ unwavering allegiance to this radical new direction in art. Degas was a maverick technically and visually.

Edgar Degas, Woman in a Loge, 1880, pastel and oil on cardboard on canvas, overall: 66 x 53 cm (26 x 20 7/8 inches), The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, The Lewis Collection, TR:377-3014

For example, Woman in a Loge, 1880, showcases Degas’ unconventional compositions. Taking a favorite subject among his modernist peers (Pierre-August Renoir, Mary Cassatt, and Eva Gonzálves come to mind), this Realist reframes the usual attractive female spectator, alone or with male admirers, sitting in her box seat, becoming yet another source of visual pleasure besides the entertainment on stage. Here we are her secret admirer, or voyeur, placed below in the orchestra seats or in a loge far away located to her left. To guide our eyes, Degas enlists the two blue ornamental cherubs flying below her gilded cage pointing toward her profile. Her lovely pale face appears illuminated, but how? Emerging out of the darkness, her head emerges out of an expanse of almost solid black. Clearly triangular and deliberately recessional to highlight the elaborate strata below, this form hovers between naturalism and abstraction.

Edgar Degas, On Stage I, 1876, soft-ground etching and drypoint on wove paper, sheet: 16 x 24.5 cm (6 5/16 x 9 5/8 inches); plate: 12 x 16.2 cm (4 ¾ x 6 3/6 inches), National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Rosenwald Collection.

Unprecedented compositions also appear in Degas’ experimental etchings. In On Stage I, 1876, the musicians in the foreground block our view of the dancers on stage. This location for the viewer seems to come from Degas’ pure imagination, because to see the dancers from this perspective, one would have to sit smack up against the musicians inside the pit, an unlikely audience location. Here Degas insinuates that modern life needs a modernist visuality to communicate the thrill of new optical experiences. In this case, the juxtaposition of widely separate planes brings them closer together on the artwork’s two-dimensional surface. The intersection of two distant planes anticipated Cubism, which interpenetrated forms and planes to highlight the ambiguity of our time/space perception. The Cubists most certainly studied Degas. Picasso’s Gang invented a role-playing game called “Faire Degas” (Acting Like Degas), a verbal jousting that they thought emulated their cantankerous idol, who lived on the rue Victor-Massé, not far from their digs in Montmartre.

Edgar Degas, Little Dancer Aged Fourteen, 1878-1881, pigmented beeswax, clay, metal armature, rope, paintbrushes, human hair, silk and linen ribbon, cotton faille bodice, cotton and silk tutu, linen slippers, on wooden base, overall without base: 98.9 x 34.7 x 35.2 cm (38 15/16 x 13 11/16 x 13 7/8 inches), weight: 22.226 kg (49 lbs.), National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon

Last, but not least, the exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay and the next venue, the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., feature the original sculpture of Little Dancer at Fourteen, begun in 1878 and completed in 1881, in time for the sixth exhibition of “Impressionists’” (the Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers). Nearly 40 inches in height, Degas fashioned a brown wax female figure in fourth position, clothed in cotton and silk with a satin ribbon tied around her real human hair, and real linen shoes covering her feet. This teenager epitomizes Degas’ concept of the “petit rat” student dancers. Skinny, gangly and somewhat awkward in her stance, she lifts her chin to convey something aspirational. Her half-closed eyes and her closed, pert mouth seem to express determination. Unfortunately, Degas’ loving care was not met with critical approval. Shocked and repelled, the reviews declared her “ugly” which devastated the artist. He never exhibited his sculptures again.

Edgar Degas, Four Dancers, c. 1899, oil on canvas, overall: 151.1 x 180.2 cm (59 ½ x 70 15/16 inches), framed: 176.9 x 207.7 cm (69 5/8 x 81 ¾ inches), National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Chester Dale Collection

Degas at the Opera runs through Sunday, January 19, 2020 at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. It opens at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. on Friday, March 1, 2020 and ends there on Friday, July 5, 2020. An excellent catalogue accompanies the exhibition with essays by former director of the Louvre and Musée d’Orsay Henri Loyrette, the general curator for the show; Marine Kisiel, curator, Musée d’Orsay; Leila Jarbouia, graphic arts curator, Musée d’Orsay; and Kimberly A. Jones, 19th century curator, the National Gallery of Art, Washington. In Paris, the catalogue is available in French. In Washington, D.C., the catalogue will be available in English. As of this writing, the catalogue is only available in French online or in bookstores in Paris.

Edgar Degas, Dancer Seen from Behind and Three Studies of Feet, c. 1878, black chalk and pastel on blue-gray laid paper, overall: 45.,6 x 59.8 cm (17. 15/16 x 23 9/16 inches), National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Gift of Myron A. Hofer in memory of his mother, Mrs. Charles Hofer.

Edgar Degas, Four Dancers, c. 1899, oil on canvas, overall: 151.1 x 180.2 cm (59 ½ x 70 15/16 inches), framed: 176.9 x 207.7 cm (69 5/8 x 81 ¾ inches), National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Chester Dale Collection

Lead photo credit : Edgar Degas (1834-1917), Ballet Dancers, 1877, pastel and gouache over monotype, overall: 29.7 x 26.9 cm (11 11/16 x 10 9/16 inches), framed: 46.6 x 43.5 x 6.3 cm (18 3/8 x 17 1//8 x 2 ½ inches), National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Alisa Mellon Bruce Collection

REPLY