Overcoat

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

It’s a vile slander and a lie, and I’m setting off to prove it. My clothing is simple and dark, not half used-up or shabby. It did not come from a thrift shop or even look like it as my friends keep saying, and that is why I am here, to do a little comparison shopping, maybe even buying, to prove my point. Here, I’ll say, shoving a shirt from the friperie in Montmartre right under their noses, this came from a thrift shop. See how thin it is from wear, shapeless, getting weak at the seams? Now look at the shirt I’m wearing. Fit and in the pink. No comparison. I’ll show them.

It’s a vile slander and a lie, and I’m setting off to prove it. My clothing is simple and dark, not half used-up or shabby. It did not come from a thrift shop or even look like it as my friends keep saying, and that is why I am here, to do a little comparison shopping, maybe even buying, to prove my point. Here, I’ll say, shoving a shirt from the friperie in Montmartre right under their noses, this came from a thrift shop. See how thin it is from wear, shapeless, getting weak at the seams? Now look at the shirt I’m wearing. Fit and in the pink. No comparison. I’ll show them.

It used to be an easy thing to find a second-hand store in Paris. Until recently, Paris had always had a large population living on the frontier of poor in old, established quartiers. If you needed to eat and had a pair of shoes or a coat to spare, you could take it to the pawnshop, but the money you’d get au mont-de-piété was less than a sale would bring and, besides, the pawnbrokers didn’t really like the indignity of dealing in old clothes if they could avoid it. The thrift shop was more or less an exchange mechanism for ready cash and unneeded clothes, the less being the commission the owner took for his pains. But Paris has grown richer—or the near poor have been shoved across the border, not into the real thing called poverty, but into the suburbs or apartment towers on the fringes of the city—and the number of friperies has been declining even if there still are a few thousand. The reason that any exist at all is that most of them have become consignment shops, reselling fashionable and perishable frippery that fashionistas can absolutely no longer wear in public while providing them with at least a down payment on the next round of equally perishable style and making it possible for those not quite on the cutting edge of couture to have the same ride, even if it is in coach, on standby, and on the next plane out or maybe the one after that.

The friperie I have found is the real thing, the old kind, and I think I’m already proving my point. The woman at the counter gives me a slightly startled look as I walk in. Even in my ordinary clothes, I am well-dressed here, no holes, no tears at the corner of my pockets, good shoes, everything my size. I think she wants to direct me to another store around the corner which I passed on the way here and would be, in her eyes, the kind of place someone like me would go into, but it’s not her business, she leaves me alone, and anyway my euros will fit as well as any in her till.

The only other customer also pays no attention to me. She is thirty or thirty-five, wearing a thin sweater and jeans. It’s getting chilly and she’s shopping for a coat: she must have come in without one since there isn’t one on her arm or draped over one of the racks. She’s looking at men’s coats, I think because they are usually thicker than women’s and go for the same prices in this store. She is very serious, feeling them, taking one at a time off its hanger, looking at each inside and out, running her hands over the seams, checking the cuffs and the hem, and then declining to try it on. She’s fascinating to watch, and I merely pretend to look at a couple of shirts and sweaters in order to keep her in front of me. After ten minutes, maybe a little more, another customer walks in. It rained earlier and he must have fallen into a puddle. He’s wet and dirty and shaking, a street person.

The lady at the counter clearly knows him, rolls her eyes, puffs up her cheeks, then exhales with drama as if to say You again? or maybe Why me? He says he’s cold, he doesn’t want to bother her, but, please, he needs something. She shakes her head, as if in despair and disbelief, and points at a heap of heavy shirts near the back of the store, tells him to take one—just one—and get out. He heads for the pile of shirts. I imagine they have done this before: he pleads, she relents on the cheap, he takes whatever she will allow and wanders off into the weather and won’t come back until another miséreux like him swipes his coat or shirt. He is her clochard, her act of charity, her cross to bear, but surely her confessor, if not God, will make an entry in the credit column for her. He shuffles toward the shirts, trying not to make a sound or take up any space at all.

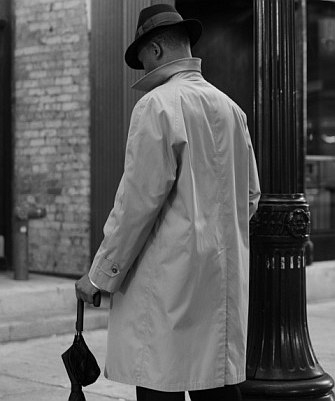

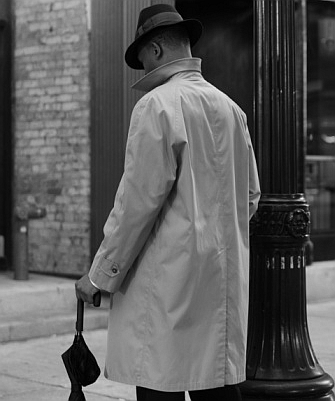

The woman who has been looking at the coats has watched as I have. This scene just played in front of us is new to her, too. She looks at la patronne and watches the ragged man sifting helplessly through the old shirts. Perhaps among the skills he is missing, like knowing how to keep a job and stay sober, you could include shopping. He is lost. She walks over to him. She’s going to help him to find a shirt that fits and isn’t likely to fall apart the day after tomorrow—good for her. But she doesn’t do that. She asks him to come with her and takes him back to the coats, pulls off a coat she had rejected—it is long and she is not—and tells him to try it on. Puzzled, a little frightened, not daring to take his eyes off her, he slowly sticks his arms into the sleeves and struggles with the buttons. The coat fits him, it actually suits him. The young woman smiles at him: his face is still frozen. Come on, she says, barely touching his arm which clearly frightens him, come on, and leads him to the woman at the counter. She counts some money out of her pocket, hands it to the owner without haggling or even asking for a little discount, and says to the man, Go, it’s all right, it’s yours. If he says merci, I can’t hear it. He keeps staring at the young woman as he backs toward the door, then turns and runs out of the store as fast as he can.

“Why did you do that?” the owner asks the younger woman. Her tone is pure hostility. She is slowly banging her fists into her thighs with anger, ready to kill, you’d think, or to throw up, she’s so angry. “Why?” she asks again. The younger woman is calm, but I think there’s anger there as well. She looks at the woman and tells her she had only six euros to buy a coat for herself, and that was the price of the coat she gave to the clochard. “But why?” “Because he made me feel better. Because there was someone worse off than I am. Because there was someone who needed a coat more than I do. I have three sweaters. I can wear them all. That will be as warm as a coat.” She walks out of the store, and I am right behind her.

She is walking away quickly and I yell to her to wait, please. She stops and waits for me, no smile, no welcome. Oui, monsieur? I tell her I heard and saw everything: it was wonderful, amazing. “No, what I said was not wonderful. It was the truth. That’s all.” Well, I thought it was. “So?” Will you let me buy you a coat or give you the six euros you spent? “Why?” Because you need a coat. “I can get by.” Yes, you can, I’m sure, but why when you can have a coat? Look, I’ll give you the money, la patronne won’t know or think ill of you. I don’t want anything. I won’t go in the store with you and I won’t be here when you come out. Merci non, monsieur. Au’voir.

No thanks, goodbye, and she’s gone. I no longer have the heart to go back inside and buy something I don’t need to prove a point to ironic acquaintances. I could to try to find the old wino with his new coat, his six-euro gift from an angel, and give him the money I would have given to the tattered angel herself, a windfall, a fortune to him, but I am too ashamed.

If you’re in Paris:

- City Segway Tours are great for seeing Paris in a different light. You’ll see more, have more fun, and not feel tired at the end of it. These are highly recommended and truly a great thing to do during your stay.

- Fat Tire Bike Tours are another great way to see the city. You’ll get the company of an expert guide, the use of a super-comfortable bike, great tips and advice about what to do while in town and an exciting, informative and educational experience.

More in Bonjour Paris, Joseph Lestrange, Neighborhood, Paris