How to Read a French Wine label

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

When I was teaching in Chateauroux, France many years ago under a French Government teaching grant, the monthly paycheck didn’t go very far. It was therefore a great treat for my fellow teaching assistants and myself to quit the grounds of the forbidding lycee, and meander off to the Bar de l’Elephant down the street after Sunday dinner. We would have a cup of strong coffee, always followed by a savory glass of red Bordeaux Superieur wine. It was fun discussing the day’s events, and if we were only well off to the extent that we could afford a good glass of wine from time to time, well, we didn’t worry much.

When I was teaching in Chateauroux, France many years ago under a French Government teaching grant, the monthly paycheck didn’t go very far. It was therefore a great treat for my fellow teaching assistants and myself to quit the grounds of the forbidding lycee, and meander off to the Bar de l’Elephant down the street after Sunday dinner. We would have a cup of strong coffee, always followed by a savory glass of red Bordeaux Superieur wine. It was fun discussing the day’s events, and if we were only well off to the extent that we could afford a good glass of wine from time to time, well, we didn’t worry much.

It wasn’t until years later that I found that superieur on the label didn’t refer to quality at all. It only meant that the wine is somewhat more alcoholic, usually half a percentage, than ordinary wine from that region. I remembered that discovery at a recent wine dinner, when a few patrons were somewhat disappointed that their wine, clearly marked superieur on the label, didn’t taste out of the ordinary to them. They were quite right.

So let’s look at a French wine label, in order to understand what the basic terms mean.

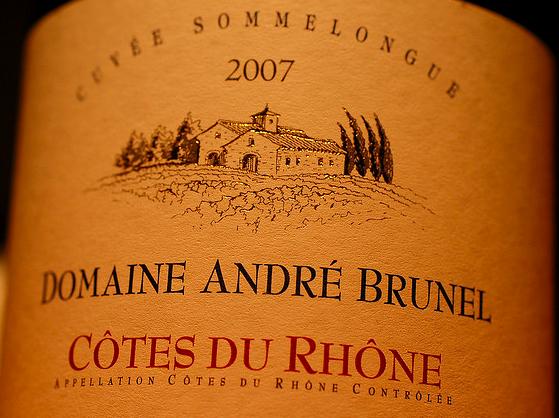

You’ll find the name of the wine, often a chateau name, easily enough, as well as the name of the producer, and the vintage year. These are your three basics. They are often enough information for the consumer, and for purposes of this column, usually recommendations are keyed to these three factors. Some say that the producer’s name is the single most important item, for a producer of integrity is a guarantee of quality wine. That is often true, and I would sometimes recommend a village wine from a fine producer over a classified wine from a producer without an outstanding reputation. But the vintage year is also of first importance. (By the way, the vintage year is the year that the grapes were grown and harvested. The blending and bottling of the wine is usually done the following year.)

The size of the bottle is also given, usually 750 ml for a bottle, or 1.5ml for a magnum. Increasingly, half bottle sizes of .375 ml for sweet dessert wines are popular, for small portions of these after dinner wines are customary. I would like to see more red wines issued in the new .500 ml size, which seems just right for two persons for a main course and dessert. Often with the regular bottle size I have some wine left over, which is always welcome the following day, but it never seems to quite hold its quality.

The size of the bottle is also given, usually 750 ml for a bottle, or 1.5ml for a magnum. Increasingly, half bottle sizes of .375 ml for sweet dessert wines are popular, for small portions of these after dinner wines are customary. I would like to see more red wines issued in the new .500 ml size, which seems just right for two persons for a main course and dessert. Often with the regular bottle size I have some wine left over, which is always welcome the following day, but it never seems to quite hold its quality.

The alcoholic content is also given on the wine label. Usually, 12-13 percent is noted, although it can go to a maximum of 14 percent. Richness in wine does not equate with high alcoholic content, by the way. I have tasted wines with 11.5 or 12 percent alcohol that were fine beverages, rich and flavorful. I have also tasted wines at the 14% level that struck me as blowsy and not of high quality. So, increased alcohol in wine is not necessarily a plus. If the winemaker is purposely striving to manipulate an artificially high alcohol level in order to promote sales, it is probably a minus, and the winemaker should be in a different business.

(Fortified wines such as sherry and port are another matter, with higher percentages of alcohol. That reminds me that other countries have their own designations. At the wine dinner I mentioned previously, some guests wondered about degrees of richness or sweetness, mentioning the term Kabinett. This is a separate German usage, quite useful in its context.)

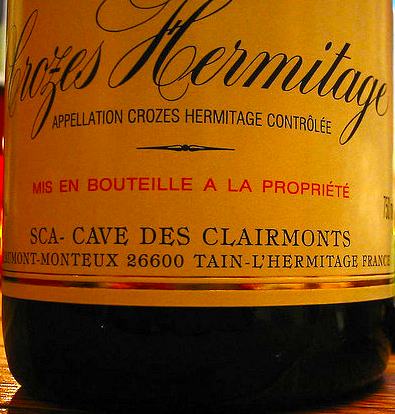

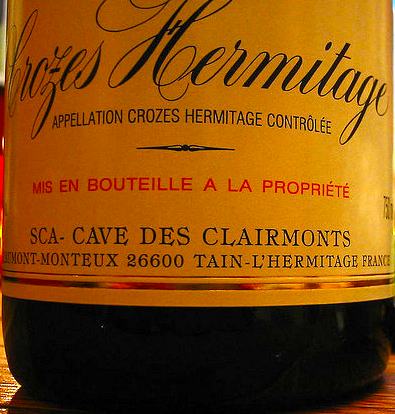

Of importance is the area where the grapes were grown, variously referred to as the appellation, often rendered as appellation controlee or AOC. The name of the region will be given here, and that is a matter strictly regulated by French law. These area designations are trustworthy, with one caveat to the careful wine purchaser. Expansion of the delimited region, as has happened in Chablis to take advantage of a popular wine, does occasionally take place. It is as bad an idea as overproduction of grapes, which also weakens the product.

The classifications of French wines, beginning with the famous Classifications of 1855 of the Medoc and the Sauternes regions, are well known. These classifications will be noted on the wine label, as a further guarantee of quality. If you are spending good money for a bottle of Chateau Gruaud Larose, a superb St. Julien from the Medoc, the label will prominently proclaim that this wine is part of the 1855 Classification. My treasured bottle of Chateau Suduiraut 1975, an excellent Sauternes, similarly notes on the label Premier Grand Cru Classe en 1855.

Wine labels will often carry the designation Grand vin by itself, without reference to a classification. What this seems to mean is that the wine is the top wine produced at the property. Otherwise, the term used will be Grand cru, as with my bottle of Chateau Suduiraut. Wines could, of course, also bear the designation Premier cru, if that is the right classification. A nice bottle of Chablis Premier cru from the banner year 2002, for example, let’s say a William Fevre Les Vaillons, would be a treat (at $40 if you can still find it). Now of course, a good wine from the Medoc region could also carry the earned designation cru bourgeois or cru artisan if that were appropriate.

Wine labels will often carry the designation Grand vin by itself, without reference to a classification. What this seems to mean is that the wine is the top wine produced at the property. Otherwise, the term used will be Grand cru, as with my bottle of Chateau Suduiraut. Wines could, of course, also bear the designation Premier cru, if that is the right classification. A nice bottle of Chablis Premier cru from the banner year 2002, for example, let’s say a William Fevre Les Vaillons, would be a treat (at $40 if you can still find it). Now of course, a good wine from the Medoc region could also carry the earned designation cru bourgeois or cru artisan if that were appropriate.

Now let’s look at some of the finer points. A wine bottled at the estate will be mis en bouteille au chateau (or a la propriete). Wines from Burgundy sometimes bear the helpful designation vieilles vignes (old vines), which may have started out as indicating that the vines survived the phyloxera plant disease in the nineteenth century. Now, they mean that the vines are at least thirty years old, as a general rule. Such wines are thought to have more ripeness in their flavor, and my experience is that that is generally true. With champagnes, of course, you have choice of extra dry or brut. The extra dry isn’t dry at all, for most American tastes, including mine. I much prefer the more dry brut champagnes.

On the back wine label, of course, comes the grim warning information that our law requires. Sometimes, to lighten the mood, the producer will include some interesting information about the vineyard, but that is not legally required. I would like to see more specific information regarding blends of grapes, but this information is usually jealously guarded by French wine producers. Still, it would add to our knowledge of the wines we enjoy.

Subscribe for FREE weekly newsletters with subscriber-only content.

BonjourParis has been a leading France travel and French lifestyle site since 1995.

Readers’ Favorites: Top 100 Books, imports & more at our Amazon store

We daily update our selections, including the newest available with an Amazon.com pre-release discount of 30% or more. Find them by starting here at the back of the Travel section, then work backwards page by page in sections that interest you.

For those who travel for French wine….click on image for details.

Support our site by clicking on this banner for all your Amazon.com browsing. Merci!

.jpg)