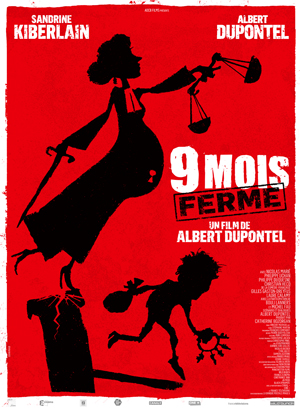

Neuf Mois Ferme: Human and Inhuman Comedy

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Sandrine Kiberlain, one of the greatest French actresses of her generation, is a wonder to behold, even physically. With a long narrow face, large, somewhat protuberant eyes, a beak of a nose, rubbery lips trying to find a shape, she looks like a female version of Ichabod Crane. That sounds unprepossessing, but Kiberlain’s looks have a weird beauty that’s emotionally affecting, just like her brandy-soaked voice. As she’s gotten older she’s used her looks and skills for comedy, a bit like Meryl Streep. Like Streep, her comic talents are theatrical: she can squeeze humor out of a corny, exaggerated gasp or a harridan’s scream.

Sandrine Kiberlain, one of the greatest French actresses of her generation, is a wonder to behold, even physically. With a long narrow face, large, somewhat protuberant eyes, a beak of a nose, rubbery lips trying to find a shape, she looks like a female version of Ichabod Crane. That sounds unprepossessing, but Kiberlain’s looks have a weird beauty that’s emotionally affecting, just like her brandy-soaked voice. As she’s gotten older she’s used her looks and skills for comedy, a bit like Meryl Streep. Like Streep, her comic talents are theatrical: she can squeeze humor out of a corny, exaggerated gasp or a harridan’s scream.

In Neuf Mois Ferme (literally, Nine Months Without Parole) she plays Ariane Felder, an uptight investigative judge, a confirmed she-bachelor who finds herself pregnant after a night of revelry she can’t even remember. That extreme situation provides plenty of opportunities for gasps, screams and a retch or two at the toilet. She’ll also have her head smacked a few times (though she gives as good as she gets).

Although the best thing about Neuf Mois Ferme is Sandrine Kiberlain, it’s also a vehicle for Albert Dupontel. He wrote and directed the movie, and is the male lead, playing Bob Nolan, an accused serial killer who may be the father of Ariane’s baby. This recipe for farce heralds back to classic French comedy. The first part of the film portrays Ariane’s detective work trying to retrace what happened on the fateful night and find the father. Ariane first suspects a colleague, an aristocratic epitome of moronic in-breeding. Her revulsion at having her genes mixed up with those of this crème de la crétinerie is tempered with French vanity about pedigree. When she discovers that the real father is actually a mad killer nicknamed the Eye-Ball Eater, comic repugnance is replaced with sheer comic horror.

If Kiberlain is one of the most brilliant actresses in contemporary French cinema, Dupontel is one of France’s best comics. His face is a farcical mask as drawn by Daumier, all stylized stupidity (but still endearing). He’s not really an actor, though. Glimmers of humanity shine through the mask, but always risk turning into sentimental schtick. On the other hand, the stupidity makes us laugh out loud. After Ariane’s discovery, Bob home-invades her apartment. He wants her to absolve him of the Eye-Ball Eating murder, but he gradually becomes suspicious about her pregnancy, as well.

If Kiberlain is one of the most brilliant actresses in contemporary French cinema, Dupontel is one of France’s best comics. His face is a farcical mask as drawn by Daumier, all stylized stupidity (but still endearing). He’s not really an actor, though. Glimmers of humanity shine through the mask, but always risk turning into sentimental schtick. On the other hand, the stupidity makes us laugh out loud. After Ariane’s discovery, Bob home-invades her apartment. He wants her to absolve him of the Eye-Ball Eating murder, but he gradually becomes suspicious about her pregnancy, as well.

The premise of the film is quirky enough. But Dupontel frequently indulges in the pretentious, baroque style of comic filmmaking fashionable in France (L’Ecume des Jours is one recent example), a style which takes quirkiness to the nth degree, often with wretchedly unfunny results. Fortunately, Dupontel himself tires of the camera and editing gimmicks and settles for funny. When it comes to funny, Dupontel has the great quality of lacking any pride whatsoever. Much of the humor in Neuf Mois is violently, gloriously Three Stooges-like.

Dupontel has also wisely chosen his supporting actors, or rather, comics. They’re all scene-chewers who clearly believe that “ensemble playing” is for wimps. Philippe Uchan is hilarious as the dorky aristocrat, who gloats about possibly having taken advantage of Ariane. (Until she finds a most painful way of extracting a DNA sample from him) Nicolas Marié gives a very politically incorrect performance as Bob’s lawyer, cursed and blessed with a monstrous stutter.

Kiberlain’s character isn’t really allowed to grow or deepen. The relationship between Ariane and Bob never really develops, either. To be fair, the script is incisive in its ham-fisted way. In France, investigating judges (similar in some ways to DA’s, but with extensive power) often tend to be callow and certain without having much life experience. In Neuf Mois Ferme our heroine learns all about uncertainty: uncertainty about an incident in her past, her lot in life, the lineage of her child, the guilt or innocence of an accused criminal, even her own guilt or innocence (when in a desperate moment she tries to self-abort). By the end of the film she at least knows what she doesn’t know. Just as the film itself stops trying to be what it isn’t and stumbles into what it is: one long, extended pratfall in the human comedy.

Kiberlain’s character isn’t really allowed to grow or deepen. The relationship between Ariane and Bob never really develops, either. To be fair, the script is incisive in its ham-fisted way. In France, investigating judges (similar in some ways to DA’s, but with extensive power) often tend to be callow and certain without having much life experience. In Neuf Mois Ferme our heroine learns all about uncertainty: uncertainty about an incident in her past, her lot in life, the lineage of her child, the guilt or innocence of an accused criminal, even her own guilt or innocence (when in a desperate moment she tries to self-abort). By the end of the film she at least knows what she doesn’t know. Just as the film itself stops trying to be what it isn’t and stumbles into what it is: one long, extended pratfall in the human comedy.

Production: Manchester Films, Wild Bunch, France 2 Cinéma

Distribution: Wild Bunch Distributions

More in film review, french cinema, Paris film, Sandrine Kiberlain