Mommy: A French-Canadian Prodigy Takes Paris by Storm

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

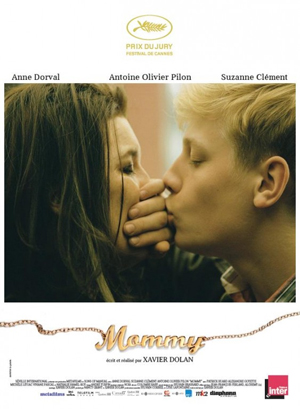

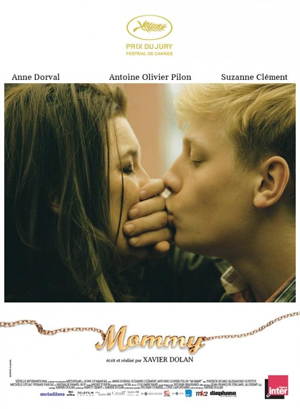

Director Xavier Dolan is considered a prodigy in France. At 25-years-old and with several Cannes prizes already under his belt, he’s being hailed as the French-Canadian Orson Welles. His new film, Mommy, has had a rapturous critical reception, and the Parisian public is flocking to this harrowing (and long) film. And Mommy is definitely worth seeing.

Director Xavier Dolan is considered a prodigy in France. At 25-years-old and with several Cannes prizes already under his belt, he’s being hailed as the French-Canadian Orson Welles. His new film, Mommy, has had a rapturous critical reception, and the Parisian public is flocking to this harrowing (and long) film. And Mommy is definitely worth seeing.

The first striking thing in the film is how it opens: with a car accident that leaves its heroine, Diane (Anne Dorval), slightly (if painfully) injured. Instead of meekly accepting help or responding graciously, she releases a stream of expletives on the guilty party and everyone else in the vicinity. That gives an inkling of the raging woman entering middle age with her élan vital intact (to say the least).

The second striking thing is the language spoken by Diane and her teenaged son Steve. It sounds like French, but as Diane says, “Not the French of France.” The accent is so thick, the expressions so particular, it sounds like Creole, or the private language of mother-and-son idiot savants. How thick? The French spoken on screen in a Paris cinema was subtitled in French. In fact, the film takes place in a suburb of Montreal where the prevailing dialect is called Joual.

The idea of a private language is appropriate—Diane and Steve are so close their family life constitutes a hermetic world. That life is so dysfunctional they make other dysfunctional families look like the Huxtables. Diane’s husband died, leaving her with Steve and a pile of debts. Steve has emotional problems that have left ADHD way behind, for violent spells when Diane fears for her safety. He is inordinately intimate with her, to the extent of virtual, at least emotional, incest. The film’s catalyst is Steve’s latest escapade, an arson episode that caused a classmate grievous injury, and Diane serious legal problems. In other words: Yikes!

What upsets the situation, or rather turns it right-side up, is the appearance of a woman named Kyla (Suzanne Clément). Kyla is a schoolteacher on sabbatical, married to an IT specialist, with a decidedly undysfunctional daughter. She seems like someone who’d normally turn away in distaste after an initial pitying glance. Instead, she becomes friends with Diane and tutor to Steve.

What upsets the situation, or rather turns it right-side up, is the appearance of a woman named Kyla (Suzanne Clément). Kyla is a schoolteacher on sabbatical, married to an IT specialist, with a decidedly undysfunctional daughter. She seems like someone who’d normally turn away in distaste after an initial pitying glance. Instead, she becomes friends with Diane and tutor to Steve.

Kyla is also a wounded person. She has a stuttering problem that’s existed for two years, about when she left her teaching job. What disaster befell her? It’s never made explicit, but we get a good idea. (Spoiler demi-alert: Just as the title comes from a pendant that Steve shoplifted for his mother, Kyla’s secret relates to a piece of jewelry that she wears.)

The first part of the film details the chaotic lives of mother and son. Dolan’s in-your-face approach to violent subject matter is similar to Jacques Audiart (Rust and Bone). It also recalls John Cassavetes, the pioneer of intense domestic drama combining a documentary style and improvisation by the actors.

In the second part, with the arrival of Kyla, there seems to be a healing process. It’s not very different from many conventional psychodramas. There are those where an exuberant non-conformist brings the uptight to life (Cuckoo’s Nest), and those where someone with good sense and decency brings the dysfunctional around (Jimmy P). Mommy belongs to the latter category.

In the second part, with the arrival of Kyla, there seems to be a healing process. It’s not very different from many conventional psychodramas. There are those where an exuberant non-conformist brings the uptight to life (Cuckoo’s Nest), and those where someone with good sense and decency brings the dysfunctional around (Jimmy P). Mommy belongs to the latter category.

Dolan overturns the convention by having the legal case cited in the beginning return with a vengeance. This doesn’t seem contrived, but some of the other narrative directions Dolan takes seem over-labored, melodramatic, and overlong. It’s possible that this young director has a grip on how situations happen, but not the experience to grasp how they play out in the longer term. Xavier Dolan still has progress to make as an artist, but he’s well beyond “promising”—he’s already a major director.

The principals are brilliant, showing the hidden depths of their characters. Diane first seems like a turbulent loser, but Anne Dorval makes us see her humor and intelligence. Kyla also could have been one-dimensional, but in a more understated way, Suzanne Clément expresses Kyla’s internalized pain and need to reach out. The revelation of the film is Antoine-Olivier Pilon as Steve, who starts off as a poster boy for taking your meds, but develops into a universal illustration of the traumas of growing up.

The principals are brilliant, showing the hidden depths of their characters. Diane first seems like a turbulent loser, but Anne Dorval makes us see her humor and intelligence. Kyla also could have been one-dimensional, but in a more understated way, Suzanne Clément expresses Kyla’s internalized pain and need to reach out. The revelation of the film is Antoine-Olivier Pilon as Steve, who starts off as a poster boy for taking your meds, but develops into a universal illustration of the traumas of growing up.

The French often complain that their films are too civilized and subtle. That’s an unfair generalization, but that feeling may be why they’re looking for visceral existential drama in a French-language film that comes from across the Atlantic. In Mommy they’ve found it.

Production: Metafilms

Distribution: Films Séville/Séville International/MK2 Diaphana

More in Cannes, french cinema