A Day Trip from Paris to Prehistoric France: The Caves of Arcy-Sur-Cure

Perhaps you’ve heard of the decorated prehistoric caves of Lascaux and Chauvet and their magnificent collections of Paleolithic rock art, and certainly, a trip to southwestern France – to the Vezère valley in the Dordogne – or to Provence is worthwhile. But would you take a week to travel to the Louvre Museum only to see reproductions of Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa or The Venus of Milo? That’s what you’d get when visiting most of the world-famous painted caves in France: facsimiles. Although remarkable enough, they’re far from Paris and, for reasons of preservation given the millions of visitors a year, high-quality reproductions.

What if you could witness the originals, a lost world of prehistoric art, indeed, the oldest visitable cave art in all of Europe, in a short day trip from Paris? You can, at the Caves of Arcy-sur-Cure, in the Yonne department of northern Burgundy, southeast of Paris. And while Lascaux and the like welcome tens of millions of tourists a year, the Arcy Caves remain an intimate, family-run operation off the beaten track, an exceptional and accessible site in the bucolic French countryside that’s a two-hour train ride from the Paris Gare de Bercy.

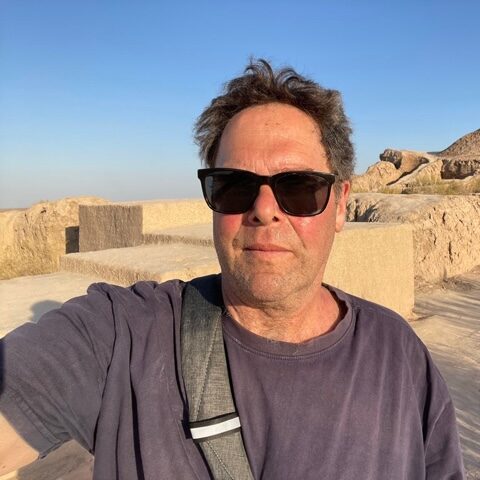

Ceiling cave paintings. Photo courtesy of the Grottes d’Arcy-sur-Cure

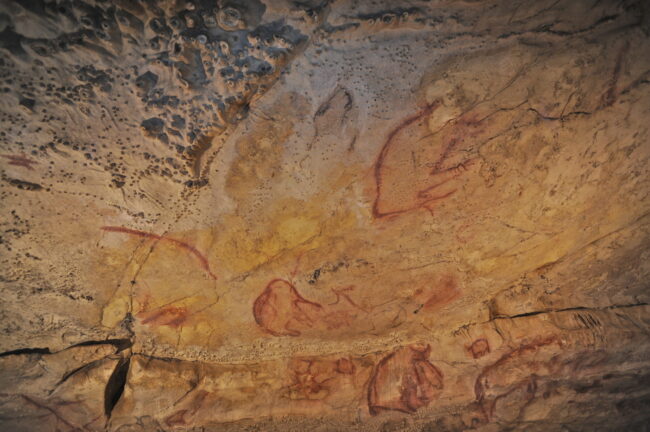

Situated about halfway between Auxerre and Avallon in the region of Burgundy endowed by countless historical sites and monuments, the Arcy Caves are a group of limestone grottos formed by a meander of the Cure river some 60 million years ago. The 14 caves born of chemical and mechanical erosion of the rock form one of the richest sites of archeological assemblages in France, having been occupied by a succession of humans – Neanderthals and Homo Sapiens – for the last 200,000 years. Indeed, the Arcy Caves have yielded some of the most important Neanderthal stone tools and ornaments known today, evidence – albeit contested – of significant cultural creativity by those “other” humans in what is known as the Chatelperronian period (45,000 – 38,000 BCE).

Even more famously, some 30 years ago, archaeologists discovered a notable series of drawings and paintings in the “Great Cave” at Arcy, which have been dated to more than 28,000 BCE, painted most probably by what archaeologists call “behaviorally modern humans,” Homo sapiens. Although they’re not as elaborate or extensive as those of some other, often far more recent sites in France, they’re a remarkable vestige of ancient prehistory that can be seen up close in a 90-minute visit along a paved path about half a mile long.

La Grande Grotte d’Arcy. Photo credit: Christian Rondet

Tourists have been visiting the caves for over 2,000 years. The via Agrippa, the ancient Roman road that connected Lyon and Boulogne-sur-Mer on the North Coast of France, runs not far from the caves, passing by the Camp de Cora, the ruins.of a Gallo-Roman bastion that too can be visited near Arcy. (It’s a lovely walk from the village, although there’s not much to see at the site, invaded today by vegetation.) Romans and other travelers were frequent visitors to the caves, as testified by the coins found in the pools formed by the Cure river within the Great Cave itself.

The Merovingians were also there, as evidenced by the nearby sarcophagus quarry, in the cliffs above the caves. In the 16th century, the caves drew the attention of scientific and literary elites in Paris as well as local notables who came to admire the thousands of stalagmites and stalactites forming elaborate accretions throughout. Some even left their marks, signatures engraved in the rock, like that of Joachim de Semizelle, lord of a neighboring village, in 1542. In the 17th century, Pierre Perrault, brother of the more famous Charles (author of the Fairy Tales) visited the caves and left the first published description in 1674, and other curious observers soon followed suit. Several even came to the caves on the orders of the king to gather rocks that were used in the grottos and garden pavilions of Versailles!

In the 18th century, Enlightenment philosophes, including Buffon (who left graffiti) and Diderot, waxed eloquently about the caves in print, and a subsequent string of illustrious visitors all left descriptions. Modern tourism began with the construction of the railroad from Paris that reached Arcy-sur-Cure in 1873, and the caves were electrified in 1910. By then, more than 100,000 tourists a year visited the caves, often taking home souvenirs that they broke off themselves.

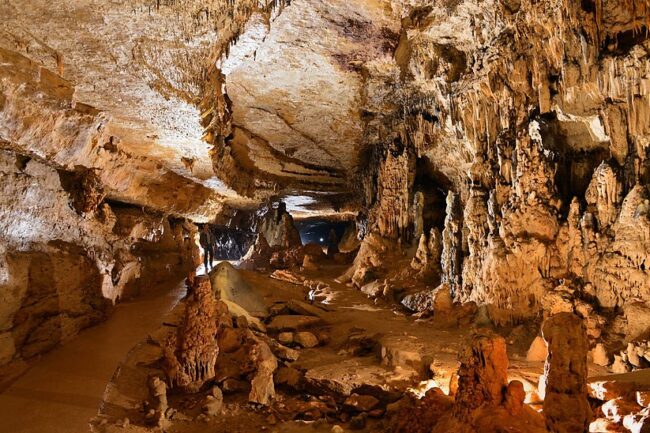

Painted mammoth. Photo courtesy of the Grottes d’Arcy-sur-Cure

At the same time, there’s a rich history of scientific research about the caves. Archaeological excavations of the Arcy Caves began in 1829 when the geologist Alexandre de Bonnard undertook work in the Great Cave, where he found a hippopotamus tooth in an assemblage over 100,000 years old, testimony to the deep history of human activity. He was soon followed by the geologist (and entomologist) Jean-Baptiste Rodineau-Desvoidy, who uncovered an equally old elephant tusk. Then came the Parisian naturalist Paul de Vibraye, whose discovery of a Neanderthal jawbone in 1858 — two years after the first Neanderthal skeletal assemblage first surfaced in the Neander valley in Germany – was the first direct evidence of human occupation.

Throughout the later 19th and early 20th century, the founding fathers of French archaeology — including the Abbé Parat and Henri Breuil — explored the caves and added to the findings that together provided firm evidence of early human occupation and industry. But the first engravings were not found until 1948, when the ethnologist and archaeologist André Leroi-Gourhan identified a mammoth engraved in the walls of the Horse Cave nearby. For the next six seasons, Leroi-Gourhan led a team of archaeologists who worked in several caves and fundamentally reshaped our knowledge of Neanderthal stone tools and culture.

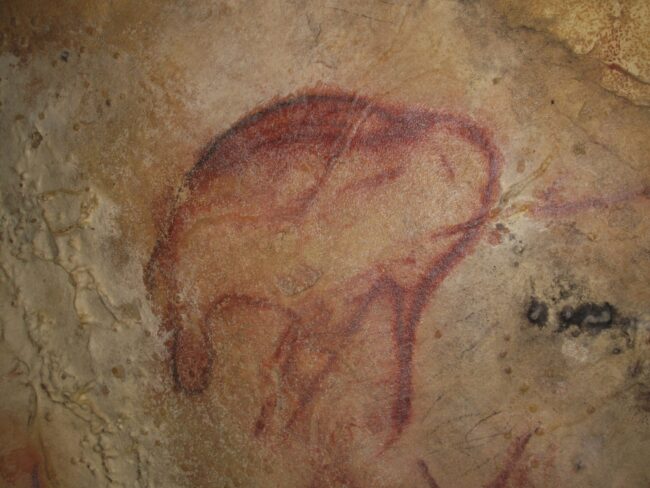

Photo courtesy of the Grottes d’Arcy-sur-Cure

It was only decades later, though, that the first paintings, hidden beneath millenia of soot from torches and layers of calcite, were revealed. The circumstances were unfortunate: to better render the remaining geological structures visible, the company charged with managing the caves began in 1976 to clean the walls with high pressure hoses and hydrochloric acid. It was only in 1990, when Gabriel de la Varende took over ownership of the caves that the process was abruptly halted, and scientists were brought in to study the first drawing uncovered: an ibex immortalized as the “Ibex of the Discovery.”

The Arcy Caves are now, of course, a classified “Historical Monument,” but they are owned privately and the visits are run as a family business. The current owner, François de la Varende, an affable gentleman of great passion and knowledge about his inheritance, lives on his property during the tourist season – from early April to mid-November – in the Renaissance Manor of Chastenay, with his son, Emmanuel. They’re devoted both to their visitors (some 35,000 a year, including groups of schoolchildren who do prehistoric drawing workshops), and to the archeologists who come from around the world to visit, document, and study the archeological assemblages and impressive collection of cave art. On any given day, you might be lucky enough to get a personally guided tour by the cave owners themselves who share their passion and knowledge, chatting in French and English with their clients.

Photo courtesy of the Grottes d’Arcy-sur-Cure

After decades of painstaking scientific work – infrared photography to locate and identify the paintings, then careful removal of the calcium layers with what were essentially dentist drill brushes – many of the 170 rock art representations can now be seen. (For reasons of preservation and difficulty of access, not all of them can be visited.) While these works of art include enigmatic ochre markings of stalagmites and the remarkable hand outlines of young children, the vast majority are composed of ferocious animals – wooly mammoths (the most represented species), but also rhinoceros, lions, and cave bears. The Arcy Caves also contain images of species rarely found in Paleolithic art, notably birds and fish. This highly unusual bestiary differs from most decorated caves, like Lascaux and Chauvet, where can be found mostly horses, stags, and bison, among others.

Why were they drawn and what do they mean? The science of dating and materials is highly sophisticated – archaeologists know much about the ways in which the caves were lit, how the paints were made, and more. But their interpretation is a wide-open field and educated guesses range widely from evidence of shamanistic cults to teenage graffiti. It’s clear, at the least, that the drawings were made for the most part in the depths of the grottos that are acoustically remarkable – places where sound echoes most loudly, suggesting a ritual as well as a decorative function that surely was associated with collective ceremonies of some kind.

The Grottes d’Arcy-sur-Cure. Photo credit: Christian Rondet

Most striking is the evidence of an “Arcy Style” of drawing, especially in the context of other parietal art. As is often the case in other decorated caves, the Arcy artists used the relief of the walls as part of their drawings, placing a hump, a leg, or a head along a rock fissure, making an eye with an existing deformity in the wall. And while there are certain representational codes that appear nearly universal in Paleolithic art – representing animals in profile, without landscape features, and without human forms, but often superimposing animals of different sizes and scales on top of each other – the way of drawing animals in Arcy was distinctive. In the Great Cave of Arcy, animals were sketched in nearly continuous contour lines, without much detail or use of color or fill. Most often, the animal’s legs are unfinished, without feet or hooves. And the horns of the mammoth are nearly always drawn as a prolongation of the head, in a single line – clear evidence of artistic license, since the “natural” prolongation of the head is the trump, not the horns. The artists – men, women or children? – who painted this bestiary all belonged to the same school: the School of Arcy.

Photo courtesy of the Grottes d’Arcy-sur-Cure

Visitors to Arcy can choose from three different tours, all in French (although there will be English-language tours on Saturdays in July; contact the author for more information). The “Discovery Visit,” an hour long, is an entry-level introduction to the geology and art of the cave, suitable for families and younger children. The “Prehistoric Visit” lasts 90 minutes and spends more time on the parietal art at the back of the cave, while those lucky enough to take the three-hour “Archaeological Visit” on Saturday mornings can wander freely among – and commune with – the paintings. You can’t take home a stalagmite of course, but there’s a gift shop packed with fossils and rocks for souvenirs.

Trains leave Paris several times a day, although visitors wishing to make the most of a day trip can take at 8h30 direct train from the quaint Gare de Bercy in Paris to the train station at Arcy-Sur-Cure, leaving plenty of time to explore the typical Burgundian village, visit its remarkable church, grab a coffee and gougère (cheese bread, a specialty of the region) at the local épicerie, and walk through the fields and forests to the caves, stopping along the way to admire (from the outside) the Renaissance jewel of Chastenay.

The return to the station is a quick 20-minute walk from the caves, which will leave ample time beforehand to wander along the Cure river outside the other caves of the site (along a well-marked trail with explanatory panels) or even (armed with a map) to visit the Camp de Cora or the Merovingian quarry. A direct train at 17h15 from Arcy will get you back to Paris by 19h30.

Photo courtesy of the Grottes d’Arcy-sur-Cure

Then again, you might want to spend a night or two, and British expats Steve and Chriss can provide a warm welcome at their very reasonably priced bed and breakfast, L’Expatisserie, at the center of the village. And of course, if you do rent a car, you can enjoy a long weekend packed with the sites and tastes of northern Burgundy: the abbeys of Vézelay and Fontenay; the medieval towns of Avallon, Cravant, and Noyers; the Gallo Romain baths and museum of les Fontaines Salées; the Abbatial, Pierre-Perthus, Bazoches, Vivier, Maligny chateaux, among others; the vineyards of Chablis, Chitry, Irancy, and more; and of course the many notable restaurants serving local fare in the region. Vaut la visite !

Historian Peter Sahlins will be offering private guided tours of the Arcy Caves in English on Saturday afternoon during the month of July 2023. Reserve your ticket directly on the official website. For questions, please contact him at sahlins [at] berkeley.edu.

Photo courtesy of the Grottes d’Arcy-sur-Cure

Lead photo credit : The caves of Arcy-Sur-Cure. Photo credit: Christian Rondet

More in Arcy-Sur-Cure, cave art, caves, Homo sapiens, Neanderthal, prehistoric