Flâneries in Paris: My Journey in Notre Dame

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

This is the 37th in a series of walking tours highlighting the sites and stories of diverse districts of Paris.

The wonderful story, said the Notre Dame app which I’d downloaded to guide my walk through the cathedral, is summarized on the building’s façade and it will unfold in more detail as you make your way round the inside of the building. The west front, it explained, faces out to the city and can be read like a book which has been carved in stone. Both the Old and New Testaments are there, for example, in the Gallery of the Kings of Judea which sits above the main doors and, just above it, the central rose window whose perfect circle has at its center the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child. Think of it as the bible explained by centuries of craftsmen, the story which could not be allowed to disappear into the flames of 2019.

Notre Dame, as seen from the entrance. Photo: Marian Jones

Most flâneries develop as I go along, intrigued by this, pausing to question that. But today, I was going to follow the app, so carefully designed to explain the mysteries hidden in plain sight in the design of the building and its stunning architectural features. The big picture, I thought, that’s what I’m after, so that on future visits I can admire whatever catches my eye and understand its context. Well, said the app, start by understanding that the central door of the three through which you can enter the building is the beginning of the spiritual journey you are walking through. It’s called the Portal of the Last Judgment.

Looking up in Notre Dame. Photo: Marian Jones

As soon as I entered, I looked up. The newly cleaned stone of the pillars and arches was what I noticed first, then the bright blues of little round windows up in the highest reaches where sunlight was streaming through. Notice, said the app, that the baptistery is right in the middle, just inside the entrance, a reminder that a journey into faith begins with baptism. There is, continued the text, a straight line from the baptistery all the way through the cathedral to the altar at the far end. The whole building is basically a cross shape and this longer axis is bisected by the shorter one, just over halfway along, known as the transept. Beyond that is the oldest part of the cathedral, the choir. Good, I thought, I’ve got my bearings.

Inside Notre Dame. Photo: Marian Jones

I followed the suggested route up the left-hand (northern) side of the cathedral, past seven side chapels dedicated to Old Testament figures whose stories form the basis of God’s relationship with His people: Noah, Abraham, Moses, David, Elijah. This section is called the Aisle of the Promise because it explains how the Old Testament stories prepared the way for what was to come. It leads to the transept, where I stopped to admire the rose window on the opposite side, the triumphant creation of the 13th-century architect, Jean de Chelles. His design, so much bigger than anything which had been possible before, used bright new blues and purples and flooded the cathedral with an ethereal light which seemed to come from God himself. It must have been mind-blowing for those who saw it in the 13th century.

St Louis chapel detail. Photo: Marian Jones

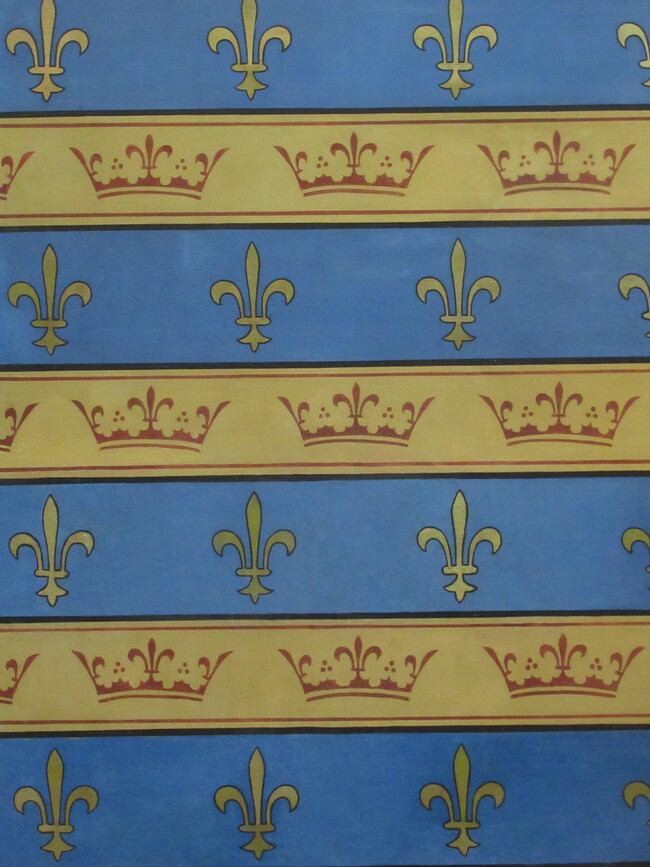

Beyond the transept came a series of 15 chapels, looping around the top of the cathedral and back down to the transept on the other side. To walk around them is to tread the ambulatory, just as medieval pilgrims did and to see the same vibrant colors – bright reds and blues, turquoise and gold – which must have dazzled them. This “medieval polychromy,” as the guidebook calls it, is especially visible in the chapels dedicated to St Louis and St Marcel, where the colors sing out in celebration of two men whose lives were dedicated to embedding Christianity in Paris. St Marcel, bishop of Paris in the 5th century, and King Louis IX, who brought holy relics back from Constantinople and built the Sainte Chapelle to house them, were both canonized in recognition of their unwavering faith.

St Louis Chapel detail. Photo: Marian Jones

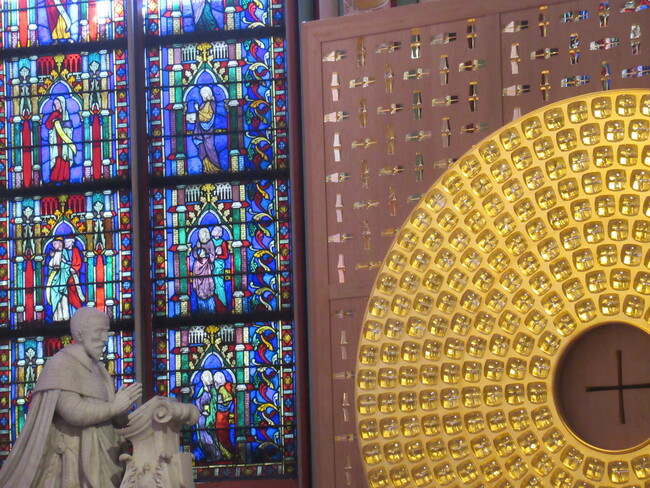

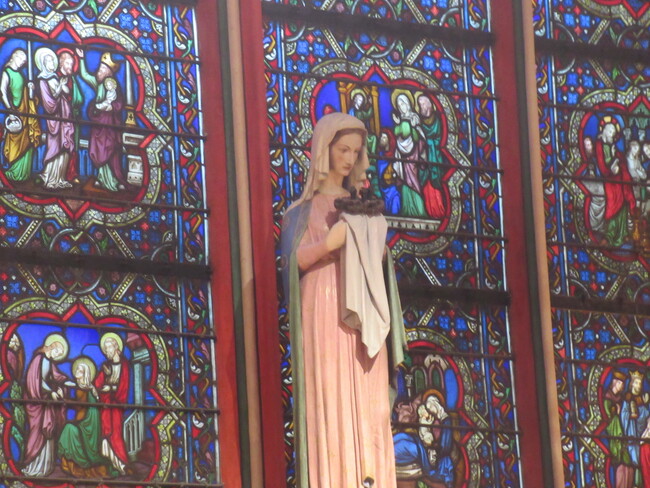

And just past their chapels, right in the center of the ambulatory and directly in line with the cathedral’s main door, is the chapel known as Our Lady of the Seven Sorrows, where a painted wooden statue of Mary stands in front of a stunning set of stained-glass windows which tell her story. The jewel-like colors contrast with the sad story told by the images of a mother whose son was born to be sacrificed. And, just in front of her was the reliquary built to house the Crown of Thorns. The crown itself is displayed only on Friday afternoons, but the golden cedarwood frame surrounding it has an aura of its own and was attracting hushed attention.

Our Lady of the 7 Sorrows. Photo: Marian Jones

In 2019, when fire ripped through Notre Dame, the Crown of Thorns was saved from the fire by quick-thinking firemen who also managed to avert the complete destruction of the cathedral which seemed inevitable to everyone watching the disaster unfold. I noticed that the great debt owed to them was expressed here, at the heart of the cathedral’s sacred space, where placards recalled the heroism of les pompiers (the firemen), the generosity of les donateurs (the donors who, a map showed, had sent money from every continent), and les bâtisseurs (all those who rebuilt the cathedral).

So far, I’ve just described what I found along the perimeter, but in the middle of the choir section I found another artwork which, on reflection, was my favorite of everything I came across. On each side is a set of charming painted stone carvings which were sculpted and decorated by medieval craftsmen as a way of telling the bible stories to those who could not read them for themselves. Again, the two sides each have their own focus. On the northern side, which I reached just after the chapels devoted to the Old Testament, came a series of scenes from the life of Jesus. This, they said, is what happened next. And there, in muted colors with golden highlights, were scenes from the first Christmas – the visits of the magi and the shepherds, for instance – and from the last week of Jesus’ life, washing the disciples’ feet and riding into Jerusalem on a donkey on Palm Sunday.

Around the other side, which I reached after passing the Crown of Thorns from the crucifixion, was another set of pictures to continue the story through scenes from after the resurrection. They showed, for example, Jesus meeting an awe-struck Mary Magdalene, encountering the disciples on the road to Emmaus and allowing doubting Thomas to place his finger into the wound in His side.

As I crossed the South Transept, I gazed across it and up at the North Rose Window, whose many panels feature the Old Testament stories to which that side of the cathedral is dedicated. And yet there, right in the center, is Mary. This was also the vantage point for a good view of the statue of the Virgin and Child, also known as Our Lady of Paris, which I’d read about at the time of the fire. Miraculously, this 14th-century sculpture of Mary, holding her son against her left shoulder and a lily in the other hand, had survived against all the odds and stands there still, serene and beautiful.

Jesus with Thomas. Photo: Marian Jones

The last section of the route, the lower southern half leading back to the entrance, is called the Pentecost Aisle, designed to explain how the faith which had been planted grew. The side chapels are dedicated to people who played their part in building up the church in Paris. Among them are Sainte Clotilde, through whose faith her husband Clovis became the first Christian king in what we now call France, Sainte Geneviève, who protected the city against a barbarian invasion in the 5th century and Saint Denis, the first bishop of Paris in whose name the “other” – actually slightly older! – cathedral was built.

There was so much more. I’d spotted all sorts of artistic treasures on my way around: statues, paintings, temporary wall hangings filling spaces where newly commissioned pieces will one day be displayed and a whole separate section called the treasury where some of the cathedral’s most precious artifacts are displayed. I will go back, and no doubt back again, to take these things in and, when it becomes possible, to explore the towers and the outside of the building.

Mary Our Lady of Paris statue. Photo: Marian Jones

But that wasn’t the plan for today. On this, my first visit after Notre Dame reopened, I wanted to understand the message which this most beautiful of cathedrals was built to convey. It’s complex and reaches far back through the ages, yet thanks to the app and the generations of craftsmen who have left us the best of their work, I felt that it was clear. I went on my way with the last line of the app’s text lingering in my mind: Dear visitors, it read, go in peace.

DETAILS

Notre Dame Cathedral is usually open from 8 am to 7 pm every day, and until 10pm on Thursdays.

Booking your visit in advance is optional, but likely to save you time in the queue.

You can download the Notre Dame app in English from Google Play Store or the Apple App Store.

Lead photo credit : North Rose Window. Photo: Marian Jones

More in Flâneries in Paris, notre dame