Hall of Mirrors

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

It’s a stupid question, I know, but I can’t help asking it. Does that man over there, so pale and fair-haired he could be albino, have a history? A future? Asking the question proves I’m either dim-witted or too self-centered for words—that I’m taking him to be a piece of scenery, a scrim upstage as I sing my aria, a spear-carrier in my own lovely opera which in length alone puts the Ring Cycle to shame. The stupid question is a hazard of my trade, of writing about people I don’t know and only see for a matter of seconds or minutes or with whom I have a short conversation.

It’s a stupid question, I know, but I can’t help asking it. Does that man over there, so pale and fair-haired he could be albino, have a history? A future? Asking the question proves I’m either dim-witted or too self-centered for words—that I’m taking him to be a piece of scenery, a scrim upstage as I sing my aria, a spear-carrier in my own lovely opera which in length alone puts the Ring Cycle to shame. The stupid question is a hazard of my trade, of writing about people I don’t know and only see for a matter of seconds or minutes or with whom I have a short conversation.

The bleached-out man wouldn’t see it my way, would think me at best his chorus boy supporting his Heldentenor and star turn, supposing he could see me at all, which I doubt. I think he is nearly blind. He always reads—always meaning the three times total I have seen him, which is my idea of his history—his book or an e-reader held two inches at most from his fat-lensed glasses, so close he must turn his head from side to side to read from the left side of a line to the right. If he can see me at all, in my black clothes and graying fair hair, I look to him like an off-color, upside-down and distinctly indistinct exclamation point. Or a sort of smear or nothing at all, depending. His point of (bleary) view or mine, either one is good evidence that Somerset Maugham got it right. The trouble with life, he said, is it never gives you the whole story.

And that is how he made his living, by making up for life, or just making it up, when life was too absent-minded to tell the tale or finish the structure. So he delicately tapped the 4-penny nails into the molding, occasionally lugged in a few joists, a window, an elegant newel post at the bottom of the staircase, and now and then the foundation, the roof and all the plumbing. Believe me, I understand. But from time to time, the whole story is there, right in front of your nose, in the palm of your hand, in your face.

Or mine. There’s a man I still see from time to time sitting in the least pleasing café in my neighborhood. I go there rarely, but it has the virtue of being open when I get up and, if my inner scold (or maybe my alter spendthrift) is telling me I don’t have to make my own coffee and my own breakfast yet again, at a little past five in the morning I can get something that passes for coffee and a tartine, provided my taste buds are still more or less asleep. But the man, he is as interesting as a real half-timbered building is interesting—it’s still there. He’s there, recognizable as a brother human, but from such a distant time from mine that I wonder that he has survived. And it’s not because he is very old.

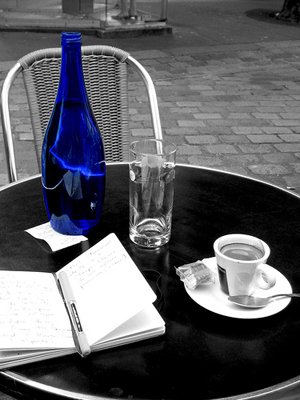

His age is not obvious as I look at him while walking by the café, but I doubt he’s yet seventy. He wears a blue beret (very French, until you actually try to buy one in Paris) planted foursquare on his head, smokes a pipe, with a slightly bent stem, which he sometimes fills with tobacco from Gitanes maïs, wears a neckerchief, also blue, knotted around his throat, and writes from time to time in a notebook. You wonder—un intello d’entre-deux-guerres or a least on of those hangers on of the café intellectuals of the Twenties and Thirties? Oh, knock it off, he hadn’t been born yet. So how and why? No one’s shooting a movie, no one pays him any attention. He drinks his coffee, sometimes a glass of red wine, writes something in his notebook, and smiles benignly at the world passing him by on the sidewalk without, as far as I can tell, ever making eye contact with another soul.

After a couple of weeks, I grow curious and go sit in the café, only a table or so away from him, always to his left because he sits to the far right side of the terrace: his chair, his table. Maybe I’ll see something, maybe figure something out. I make a point of passing by his table to steal a look at this notebook, but his handwriting is small and I can’t make out a thing. Now what? I just sit and watch. After a few days, and for the first time, the waiter comes out and points to his coffee cup. Blue-beret stares, then nods slowly. The waiter brings the coffee. I leave.

After a couple of weeks, I grow curious and go sit in the café, only a table or so away from him, always to his left because he sits to the far right side of the terrace: his chair, his table. Maybe I’ll see something, maybe figure something out. I make a point of passing by his table to steal a look at this notebook, but his handwriting is small and I can’t make out a thing. Now what? I just sit and watch. After a few days, and for the first time, the waiter comes out and points to his coffee cup. Blue-beret stares, then nods slowly. The waiter brings the coffee. I leave.

One more try. He’s writing something in his notebook when I decide to head for the WC, say Bonjour and ask him if he’s a writer. He looks up at me slowly, gives me the A-Team version of his benign smile, and goes back to writing… without looking directly at the page. I think maybe I’m getting it. A few days later, I pass the café much later than usual, getting on for six in the evening. He’s drinking a un gros coup de rouge and smoking. I perch and wait, longer than I want given the wine the café has to offer. But she comes, at last, I knew she would and she took her sweet time, but she comes.

She’s a woman of forty, could be, though no easier to place in a human chronology than the man. But when she pulls up in her elderly Citroën Deux Chevaux there is no surprise. Her clothing is Thirties boho: at least three layers of flowing and flowery stuff, no doubt the citadine idea of peasant dress, a quirky little hat, not quite a cloche, a cloth handbag, big enough to supply me for a long weekend. She puts her hand on the man’s shoulder, he smiles, then she nods through the doorway and the waiter comes to take money from her. She gives the old boy…oh, why not? She gives her father a little tug on his left elbow, and he rises at her touch. With her right arm through his left and her left hand clamped on his forearm, she makes her way to the jalopy, opens the door and helps him in, slightly pushing down on his shoulder and then his head.

It‘s sweet, you could say, father and daughter sharing some fantasy of the good old days or whatever the hell they really were, the wonderful old days neither of them ever saw, if that makes a difference or even sense. No harm in that or in either of them, not a gram’s worth. Dotty or deaf or somehow alienated from this place and this time, he gets dropped off dutifully by his daughter every morning at Café Day-Care, and when she gets off work, she comes and collects him, and home they go to a silent and smiling dinner and evening and then to bed and, tomorrow and tomorrow, repeat.

Maybe it’s not the whole story, but as much as I’ll ever figure and as much as I ever want to know. Part of me wishes I had left it alone, that same part that tells me not to stick my nose or my oar in, that tells me that what I don’t quite understand is not necessarily mysterious or even worth puzzling over and finally tells me to go away and not come back. I listen and nod—good advice.

The the whole story of the bleached-out man I’m looking at today is his for now and forever as far as I’m concerned. I think.

photo 1 by John Althouse Cohen [CC BY 2.0], via Flickr

photo 2 by hans van den berg [CC BY 2.0], via Flickr

More in bleached-out man, french life, Paris cafes