Author Mary Duncan: Life in Paris, Shakespeare and Co in Moscow

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Mary Duncan grew up in National City, California, a blue-collar suburb of San Diego. Her father died when she was just four years old, and her mother worked in a bar to support the family. Mary summoned the determination and resourcefulness she needed to go to college, where she excelled; eventually she became a professor and department chair at San Diego University. Her academic research on playgrounds in war-torn countries took her to Belfast, Teheran, and Managua, and into some precarious situations. In 1988 she was invited to attend a conference in Moscow sponsored by the Soviet Peace Committee, where she met and fell in love with Yuri, an architect; a year later they married, and in 1996, Mary co-founded the Shakespeare and Company bookshop in Moscow.

She now divides her time between La Jolla, California and Paris, where she founded the Paris Writers Group, Paris Writers Press and the Paris Writers Atelier. She is the author of Henry Miller Is Under My Bed: People and Places on the Way to Paris, a lively and thoughtful memoir of a fascinating life. Mary recently took the time to answer Janet Hulstrand’s questions about her love of Paris, as well as about some of her many adventures, both literary and other, for Bonjour Paris.

Poilane bakery. Photo: bongo vongo/ Wikimedia Commons

Mary, you write so beautifully about the power of Paris to nurture creativity and transform lives. How did Paris become so important to you? Was it love at first sight, or was it a love that grew over time?

I think it was love at first sight. A friend in San Diego owned a large studio apartment on rue du Cherche Midi across from the Poilâne Bakery. During the 80s, I stayed there whenever I was in Paris. Bradley Smith, a La Jolla friend and Time-Life photographer, sent two letters of introduction, one to George Whitman, owner of Shakespeare and Company, and one to Kathleen de Carbuccia, one of the founders of AARO (Association of Americans Resident Overseas). They became my first new friends in Paris.

I found myself living on one of the most fashionable streets on the Left Bank. Countess Brandolini, who owned the right side of our building, hosted glamorous parties. The owner of Club Med lived in the penthouse. Andy Warhol had the apartment above me. Warhol and I would nod in the courtyard — and the concierge snuck me into Warhol’s fascinating abode, with his closet full of antique military uniforms. That was in 1981.

I decided that when I retired from San Diego State University (SDSU), I would live in Paris and create a literary life. My academic career would be a part of the foundation. After that, every major decision was factored into that goal. In those days before emails and iPhones, I kept handwritten notes on almost every person I met and reviewed them prior to each Paris trip. I was a newcomer. It was up to me to stay in touch and remember them, not the opposite.

Organizations like Democrats Abroad, the American Library, Shakespeare and Company, and Sunday dinners with the late Jim Haynes, were my homes away from home. They included me, and I am forever grateful.

When I retired early from SDSU in 2000, I purchased an apartment in Paris. l live here now about nine months of the year.

Paris nourishes my soul. I’m alive, intellectually, personally, spiritually. I thrive on the diversity of people, the cultural events, the food, the public transportation and opportunities for growth. It’s true that you can reinvent yourself in Paris. But you have to make the investment in order to reap the rewards.

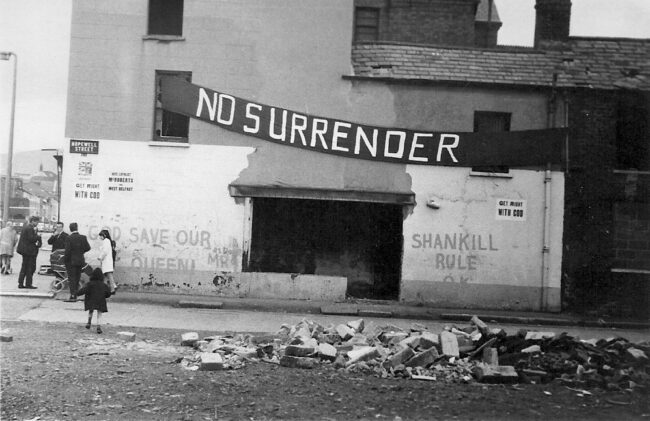

Loyalist banner and graffiti on a building in the Shankill area of Belfast, 1970. Wikimedia commons

You spent quite a bit of time in Belfast, Northern Ireland at the time of “the troubles.” People really need to read your book to know what you were doing there — but for now, I’m interested in how you feel your work there affected the rest of your life going forward.

In 1974, I was an ambitious young assistant professor who wanted the gold ring — to be a tenured full professor. A small grant to conduct research in Belfast on children and political violence became my fast track to that goal.

After my first trip to Belfast, my life was like a can of whipped cream. You can’t put your experiences back inside the can. I was changed forever. I felt if I could survive Belfast, I could do anything. My dean at SDSU once asked why I was so calm during raucous faculty meetings. “Everything is relative,” I replied. ”No one here has a gun.”

Self-induced adrenaline became my drug of choice. I was more afraid of dying bored, than of dying. From Belfast I traveled to Nicaragua, Teheran, Cuba, Moscow, Berlin, and I lived in a squatter village in Mexico. I also spent two nights in Delhi with families camped under a highway bridge.

But my dream to live in Paris would be the culmination of my academic career.

Hôtel de Chambon on the rue du Cherche-Midi. Wikimedia Commons

Your life is full of so many fascinating twists and turns that I hardly know where to start. But perhaps I will ask you to say just a bit about the time you spent at the Playboy Mansion, for example. How did that come about?

Most women who were at the Playboy mansion were there because of a man, and I was no exception. In 1976, I met Max Lerner, the syndicated columnist and writer, at an academic conference in Palm Springs. We were both married. I was 35. He was 69, twice my age.

I was a professor, and a protestant minister’s wife. Max pursued me for two years via phone calls and notes attached to his newspaper columns. His odds improved when he started teaching a class at a private university in San Diego; as they say, proximity is everything. When he invited me to have lunch at his friend’s home, I didn’t know my host would be Hugh Hefner. “Breakfast at Hef’s,” a chapter in my memoir, and an article I wrote for the Huffington Post, describes my favorite hour at the Mansion.

For me, Max and the Playboy Mansion were an intellectual mecca. Breakfast at Hef’s included fascinating conversations with film directors, movie stars, writers, and other celebrities. The Mansion had butlers, who were usually grad students from the nearby UCLA campus. They also had 24-hour kitchen service, a film library, an open bar, a pool, sauna, a tennis court, masseuses, a gym, a guest house with three small bedrooms for privacy, and a zoo. Max said staying at the Playboy Mansion was better than a five-star hotel because you never received a bill.

Breakfast at Hefs

Next to Paris, the Mansion was my favorite place to write, read, study, think and socialize. Only my closest friends knew I was spending time there. My feminist friends were appalled, but curious.

I felt like I was walking on the edge of life again. Even as a child, I liked walking on the edge. The Girl Scouts kicked me out for adding a nickel to every box for myself, which explained why I was their number-one cookie seller. A sorority expelled me for organizing a pledge rebellion. No one appreciated my wayward leadership skills.

With Max, I was definitely walking on the edge, but the IRA had taught me some survival skills, including identifying your personal attributes. Mine were being a five-foot blonde female with blue eyes, a friendly smile, an innocent demeanor, and intelligence. I was also a physical threat to no one, and I was a late bloomer. Most of my life people underestimated me.

Grand Kremlin Palace with the Kremlin wall, Moscow. Photo: W. Bulach/ Wikimedia Commons

Your memoir details how you went about founding a Shakespeare and Company bookshop in Moscow. The bookstore — which must have been a wonderful resource for readers of English-language books in Russia —survived for seven years (1996-2003). What thoughts and memories do you retain about it 20-some years later?

I thrived in Moscow because there were few rules. We made our own. Yeltsin was president. Daily life was in flux. People were adjusting to a new version of capitalism.

Our Saturday night book events featured the poets Yevgeny Yevtushenko and Andrei Voznesensky, novelist Victor Erofeyev, Tatyana Tolstaya, diplomats, and CIA and KGB operatives. All mingled together with our customers. Our well-stocked lounge (vodka, red wine, Starbucks coffee) made us the only bookshop in the world where you could get tipsy while browsing.

In those days, Delta’s free baggage allowance was three 70-pound bags. A 20-dollar bribe to the porter got my books past Russian customs. Porters practically fought over who would help me when I arrived.

Even before we had a location, George Whitman rode a train to Moscow with a pretty college student and brought us four boxes of contemporary books. His confidence in our success propelled us forward.

George Whitman at his 97th birthday party, doing what he loved best . . . reading. © Meredith Mullins

Shakespeare and Company Moscow was one of my greatest accomplishments. I didn’t speak the language. I had never run a business (other than selling Girl Scout cookies). My Russian partner owned a nearby Russian language bookstore. He handled the day-to-day operations. I kept the new books flowing and planned the events. We purchased over 300 full-color bilingual children’s books for a nickel each, and every child left the shop with a free book. Yuri was always supportive, helped where needed, and kept me supplied with black caviar.

A well-dressed banker who loved Vonnegut protected us from the mafia. When anyone bothered us, we handed them his card, and they disappeared. Spasso House, the elegant American ambassador’s residence, invited us to their cultural events, where we drank champagne with Christiane Amanpour and other influential people.

Then Yeltsin resigned. Bribes demanded by the new “officials” closed our doors.

Twenty-five years later, our Shakespeare and Company sign is still hanging over the doorway. The basement shop is closed, but the memories still fill me with a love for the Russian people and the expats who were our loyal customers.

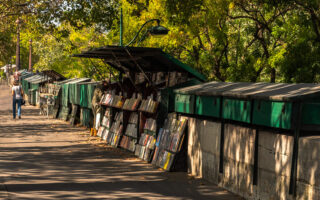

Rue de la Bûcherie in Paris. Shakespeare and Company. Photo: Tom Fahy’s/Flickr

I love the way that in your memoir you have shared not only the many adventures you’ve had in far-flung parts of the world, but your hard-earned wisdom about life and love, as well as some of the important things you learned along the way from friends — people like Max Lerner, George Whitman, and members of the Irish Republican Army, who you came to know quite well during the times you spent in Belfast. What is the most important piece of advice you ever got from someone else?

My paternal grandmother said, “If you buy property when you are young, you can have anything you want when you are old.” I listened to Grandma. For me, an economic foundation is an essential part of living an independent, productive life. Another important lesson is to live within our means. Debts and credit cards often represent modern-day slavery.

The first article I wrote for the Huffington Post, “How I Retired Early and Moved to Paris,” was read by over a million people. When I received letters from readers with similar dreams, but with “buts” in them, I knew they would not succeed. We have to ask how we can overcome all those “buts.”

From Max Lerner I learned that without an intellectual life, there is no life. From George Whitman, who provided free beds to thousands of struggling travelers, I learned to be generous. From the IRA I learned that nice people can be killers.

In my memoir I share some of the advice I received on life and on love from Max, who believed in the importance of eros in our lives. And I quoted a wise older friend on the “five F’s” of keeping a man. Her advice probably sets feminism back 50 years. But it works.

What is the most important thing about life that you learned from following your own path, and living life on your own terms?

Don’t ask for permission. It only gives someone the opportunity to say “No.” When caught or questioned, don’t make excuses. Apologize; first ask for forgiveness, and then ask for advice. Frankly, if you move with confidence, most people assume you know what you are doing, even when you don’t.

There are no free lunches. Be prepared to pay the price for the choices you make. Thrive on your successes and keep moving forward. Learn from your mistakes. We only have one life. Some may believe in reincarnation, but I’m not taking any chances.

Mary Duncan and writer Jean-Jacques Pauvert, 2014

How and why did you start the Paris Writers Press?

In 2008, Starhaven, a small British press, published my memoir, Henry Miller Is Under My Bed. Two years later I wanted to revise it, and add photographs and a new cover. Chip Martin, my brilliant publisher, didn’t have time to do it. After my continued persistence (okay, nagging), he let me buy the rights to the book.

Without knowing anything about the publishing business, I started the Paris Writers Press. We have published six books and received a Centre National du Livre (CNL) Translation Award from the French Ministry of Culture. Our authors and books have a French-American connection. Creating Paris Writers Press had a very high and expensive learning curve. Mistakes were made, but we are proud of our little press. Due to time constraints, we are not currently accepting submissions.

Henry Miller is under my bed

What are you working on now? And what’s next for you?

For the past eight years I’ve been writing a book about the cultural and literary history of a small street on the Left Bank. Completing that book this year is my top priority.

I’m also working with a couple of videographers on a video to highlight the Paris Writers Group and the Paris Writers Atelier, which we hope to release this summer.

You told me to ask you what your greatest faults are. I think this alone says a lot about the kind of person you are. So — okay: what are your greatest faults?

I’m too slow to ask for advice. Sometimes too trusting. When I’m in a hurry to create something, I don’t consult with people because it takes too much time. I don’t break things but I do crack them. Then I have to patch them up.

How about your greatest virtues?

Persistence. A positive attitude. Not taking NO for an answer. Always functioning with alternatives. Loyalty. A sense of humor.

I was always told that my family descended from bootlegging Irish Catholics. A DNA test questioned part of that story. DNA shows that I’m 48 percent French-German with almost equal parts Irish, Scottish, and English. An elderly aunt told me that she had heard that my maternal great or great-great grandfather was a French trapeze artist who fell to his death. This could explain why I like walking on the edge. Maybe it’s in my genes.

Perhaps a genealogical search should be on my list of future things to do.

Lead photo credit : Author Mary Duncan

More in books, Interview, People