When Paris Sent its Mail Down the Tubes

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 80 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Forget email, SMS and WhatsApp – if you wanted to send a message quickly to someone in Paris in the 20th century, you would have used the pneumatique. Mention it to a Parisian of retirement age and they will know immediately what you are talking about. It’s 40 years now since this remarkable means of communicating across Paris finally shut down but it still lingers in people’s memories. Its petits bleus lettercards are as evocative of Paris as Robert Doisneau’s black and white photographs, both nowadays evoking a city gone forever.

The Paris pneumatique was not the first system of its kind but it was the most extensive in the world. The concept of pneumatic post developed as a response to the electric telegraph. This was the technological marvel of the early 19th century; for the first time in history messages could be sent and received in minutes instead of days. But its popularity was such that by the middle of the century, the capacity of telegraph systems in large, densely-populated cities like New York, Paris and London was saturated and delivery times slowed down. This was a problem for business and, in particular, stock exchanges, which had come to rely on the rapid exchange of information. In addition, messages had to be encrypted and then decrypted from morse code. Wouldn’t it be better if letters in plain language could be transmitted just as quickly?

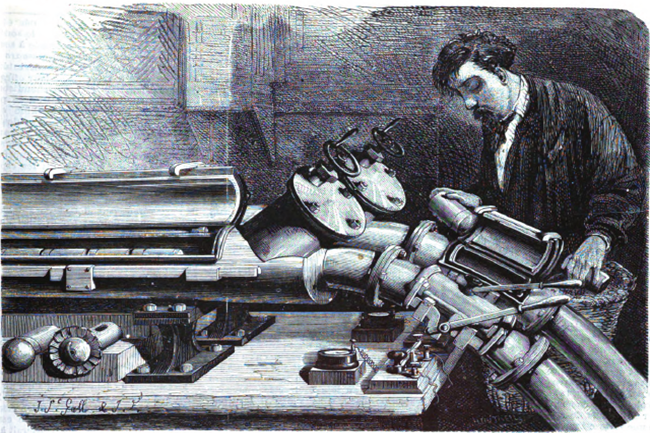

The steam plant for the compression of air and its rarefaction, at the Hôtel des Postes, in Paris. Image: Louis Figuier/Wikimedia Commons

It was as an extension to the telegraph service that pneumatic services came into existence. London opened the first pneumatic post in 1853. In Paris the telegraph network was overloaded and faltering by the 1860s to the extent that people were reverting to sending letters by road transport, with all the delays that entailed. Emperor Napoleon III of France ordered the construction of the French capital’s own pneumatique.

In 1866 an experimental 1km stretch was opened between the Bourse and the Grand Hotel on the Boulevard des Capucines. In 1868 the first official line was opened, linking government ministries with the Central Post Office, then situated in Rue de Grenelle. For the next 11 years the network remained “closed” in the sense that it served only official institutions, but gradually post offices were incorporated and in 1878 the postal and telegraph services merged into one company: P&T (Poste et Télégraphe, later to become PTT with the addition of telephones). In the following year the pneumatique was opened up to the public. It quickly became a faster, alternative method of posting letters.

A map of the Paris pneumatic tube network in 1888. Louis Figuier. Public domain.

The technology was actually quite simple and had been invented in the 1830s by a Scotsman, William Murdoch. Letters were placed in small capsules, which were then dropped into metal tubes. Compressed air operating in a push-pull manner whooshed the capsules round the city at speeds reaching 40km an hour. The tubes were laid through the sewers, alongside railway and, later, Métro, lines, and across bridges in a network that covered every neighborhood. There was still an element of old fashioned mail delivery: letters were dropped into separate pneu mailboxes on the street and at the other end, the capsules arrived at specialized collection centers where dedicated couriers called tubistes delivered the letters to individual addresses. All the same, letters could be delivered within a couple of hours.

The network continued to expand throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries and at its peak stretched 427km in length with 130 offices. In 1945, its busiest year, it handled 30 million letters. Although the tube network only covered inner Paris, by the 1930s you could post a letter to Paris from some of the near suburbs and it would be taken to the nearest collection center within the city boundary.

Everything from business letters, invitations, love letters, theater and cinema tickets zipped down its tubes from one end of the city to the other at the speed of a telegram. The great advantage of the pneu over telegrams, though, was that you were not charged by the word. Correspondence could be written in full sentences and full-length letters could be written for the price of a pneumatique stamp. The only constraint on length was the size of the special cards that were used.

Booster-depressant group in use in 1984 in the postal pneumatic tubes network of Paris. Photo: Jérome Ferri/ Wikimedia Commons

The stationery went through various versions, starting with doublesided cards with perforated gummed edges. The recipient would tear off the perforated border to open the letter. In 1880 reply cards were attached and in the same year new stationery was designed by the sculptor Jules-Clément Chaplain – a design that lasted for the rest of the pneumatique’s existence. Later, the reply card was withdrawn and envelopes introduced and for a while you could use ordinary envelopes as well. These were dropped in 1942. But the basic pale blue card lasted until the service’s closure and earned the nickname petit bleu.

Convenience came at a price. Pneus cost around four or five times the price of a normal letter, so you would only send one if the message was urgent or particularly important. As time went on, they became superseded by the telephone. By the 1970s the cost was eight times that of a letter, and in 1984 the system was finally closed down. By this time even the telephone was starting to make way for new technologies such as telex and fax and – France’s own precursor to the internet – the Minitel.

“Petit bleu” of the pneumatic post with a stamp of Jules Chaplain. Public domain

You can still pick up the cards in postcard and philately shops or at flea markets. In the same way old black and white postcards with their brief messages between friends and family evoke vacations and excursions from long ago, pneus transport us into the daily minutiae of people’s lives: lovers’ meetings, theater and cinema rendezvous, railway station arrivals and departures. There is a touching and evocative journey of a pneu in François Truffaut’s film Baisers Volés (Stolen Kisses) where a lover’s break-up letter is seen whizzing down the tubes as it crosses Paris to its sad destination. (See the YouTube extract here.)

Pneumatic post-office tube terminal Fortin-Hermann, 100 years old still in use at Paris-Central in 1987. Photo: Jérome Ferri/Wikimedia Commons

While the public pneumatique is long gone, the technology is still widely used. Banks and supermarkets use pneumatic tubes as a defense against hold-ups; you may well have seen the cashier put a roll of banknotes into a tube beside the cash register that drops directly into a safe. Hospitals, in particular, use pneumatic tubes to transport blood samples rapidly and securely to laboratories. In France, more than 300 hospitals use a pneumatic network, the largest being at the Hôpital Cochin in Paris, which has 14km of tubes and 150 collection points. These days it is computer-controlled.

And a Government network lasted until the early 2000s linking different departments, and the National Assembly and Senate (this only closed down in 2004). Even today, there are dedicated tubes linking the Elysée Palace and the Hôtel Matignon (the prime minister’s official residence). These have an important security function: in the case of a national communications breakdown, perhaps during war, the country’s two most important leaders will still have a method of communicating.

But it is the humble petit bleu that reminds us of the period of Paris’s history when the fastest communication meant sending a letter down a metal tube propelled by compressed air.

Lead photo credit : The receiving and sending device of a pneumatic tube, Photo: Wikimedia Commons

More in history, mail, mailing, pneumatic post, Poste pneumatique