The Dandy Criminals who Terrorized Paris

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

France and Paris have plenty of stereotyped images associated with them, but one of the most enduring is that of the Apache. Even if the name is unfamiliar, the image persists of a ruffian-looking man wearing a striped Breton jersey, neckerchief and waistcoat, and his girlfriend sexily dressed in another Breton jersey and tight black pencil skirt slit all the way up the thigh, the outfit usually accessorized with a beret. Right through to the 1960s, they personified the dangerous but sexily glamorous underworld of Pigalle. In the popular imagination they supposedly hit the dive bars and dance halls of Montmartre with their exciting Apache Dance – a combination of sultry, close dance steps and a lot of throwing-around (of the woman, that is).

The Apache dance. Leo Rauth, 1911. Public domain

The Apache costume and dance have become clichés in the iconography of Paris but at the turn of the 20th century the Apaches were seen as a real threat to law and order. The origins of the name are uncertain, but it’s thought to refer to the Native American tribe, although by 1902 it had been vanquished and its leader, Geronimo, had become an international celebrity (the name in French is pronounced ‘A-pash’).

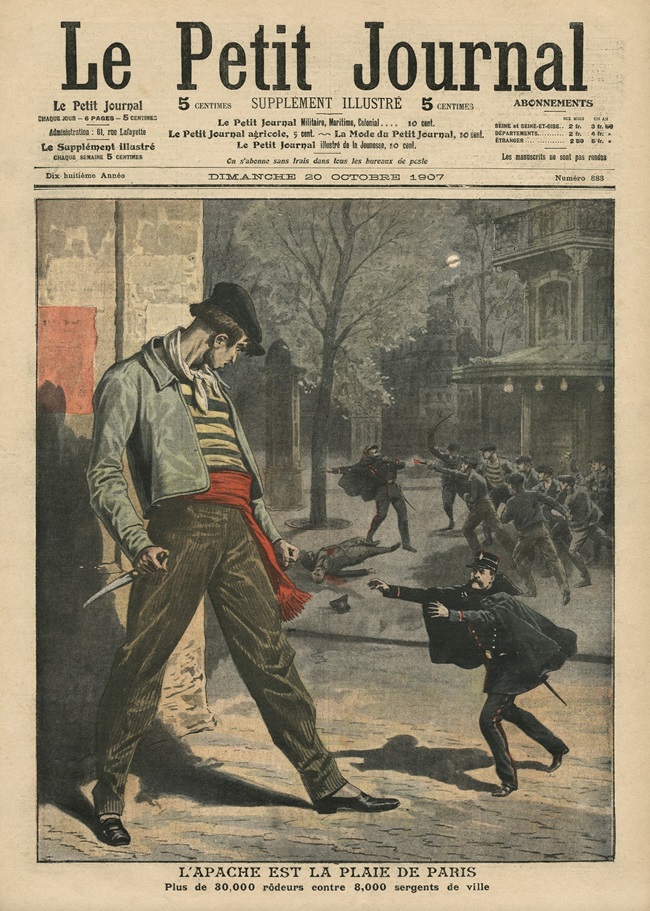

Apache is a nuisance for Paris. Illustration from “Le Petit Journal”, 1907. Wikimedia commons

The Apaches represented an early form of semi-organized crime, with gangs carving out territories in particular working class quartiers, especially of northern Paris in the 17th, 18th and 19th arrondissements. The superficial glamor associated with Apaches hid a life that was brutal, slum-ridden and almost certainly destined to be short. By and large they were petty criminals, specializing in muggings, inter-gang warfare, and general hooliganism.

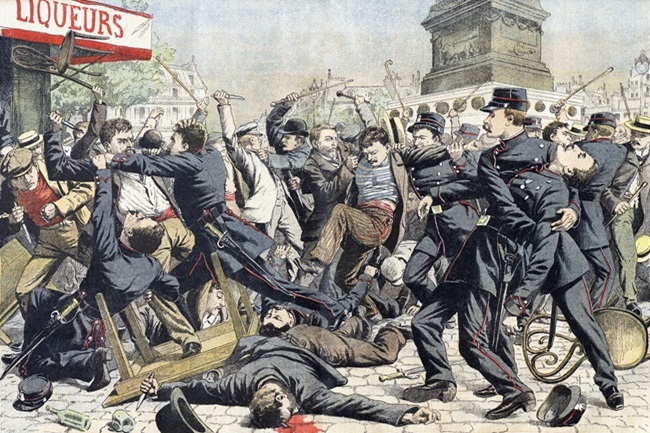

To the respectable bourgeoisie they were Public Enemy No. 1 but they appeared more threatening and dangerous than they probably were, largely due to their escapades being magnified in the popular press. A 1907 cover of the popular magazine Le Petit Journal shows a giant Apache facing off a tiny policeman with the strapline “30,000 Apaches against 8,000 policemen.” There was definitely an element of the gangs and the press feeding off one another to pump up their notoriety.

“Apache customs. Atrocious revenge of a prowler.” Le Petit Journal, 19 May 1907. Public domain.

One thing that did make them stand out against other criminals was their appearance. The male Apache paid a great deal of attention to looking good. The common elements comprised a striped marinière, or Breton jersey, a red neckerchief and a red silk sash around the waist like a cummerbund. To this he added a natty waistcoat, a flat cap à la Peaky Blinders, and fancy shoes. Bright yellow leather with golden buttons was particularly favored but if he couldn’t afford the boots, he would often wear espadrilles. Apache fashion caught on for a while in the mainstream and clothing stores sold “typical” Apache outfits.

Apaches also pioneered the custom of tattooing, especially to signify gang allegiances. One gang was actually called Les Tatoués (The Tattooed); when they were caught in 1902, members’ bodies were covered. Common tattoos included a blue dot under the left eye, a ring of dots along the neck (to guide the guillotine which gang members always expected to be their fate), and five dots like a domino piece which signified the wearer had spent time in solitary confinement.

les Apaches de Paris, a novel by Jules de Gastyne. Public domain.

Although the headlines in the penny press were melodramatic, it would be a mistake to underestimate the violence of the Apaches. Tucked into the sash they would always carry a cudgel or knife, and they carried an unique kind of gun. The “Apache revolver” had no barrel; instead it fired via a pinfire cartridge often used in contemporary rifles, and a folding blade extended from the chamber. The grip was made from knuckle dusters. Apaches had a particular MO as well. They attacked their victims from behind and strangled them with a scarf – sometimes to actual death – in a move called the coup du Père François, while other Apaches went through the victim’s pockets. Headbutting, pulling the victim’s legs from under him, and pulling his jacket over the arms and head were other methods of disorienting and overbalancing a victim, all the better to empty his pockets.

Women may not have been as violent but they played their own role in picking out victims. They were gigolettes – pretty, young (to the point of being underage by modern standards), they worked as prostitutes for their Apache pimp, and distracted and enticed likely-looking men into alleys to be jumped by the male gang members.

Apache revolver. Photo Credit: Latente Flickr/Wikimedia Commons

The Apaches started to appear in the last years of the 19th century but it was a cause célèbre in 1902 that rocketed them to national notoriety. This was the case of La Casque d’Or, who in reality was a gigolette called Amélie Hélie who happened to have a magnificent head of strawberry blonde hair – hence her nickname. Amélie had got herself involved with two feuding Apaches called Leca and Manda, playing one off against the other. Several times the two gangsters tried to kill each other, climaxing in a gun battle near Bastille. Eventually they both ended up serving their sentences together in the same penal colony. Meanwhile, Amélie lived off her celebrity for a few years, although she ended up as a brothel owner and later a circus animal tamer. When she died in 1933, aged 55, no-one actually remembered who she had been. She was played by a young Simone Signoret in the 1952 film Casque d’Or.

Amélie Élie, around 1900. Public domain.

So what about the famous Apache Dance? Its origins are uncertain, although around 1903 the music hall star Mistinguett claimed to have developed an early form she called “The Cakewalk of the Barrières” (the barrières at that time being synonymous with the poorest neighborhoods on the very edge of Paris’s boundaries) and described as a mock fight. The dance hit public consciousness in 1908 when two male dancers, Maurice Mouvet and Max Dearly, created as “definitive” a version as it was possible to be. The “story” centers on a domestic fight between a prostitute and her pimp. He demands her money, she refuses, cue the pimp mock-slapping and punching the woman and throwing her around the floor. She fights back and is rewarded by being dragged by her hair and whirled in a circle before being flung in the corner. Finally, the couple make up over a physically close dance that incorporates steps from the tango and the waltz. Politically correct it definitely is not, although some people have referred to Mistinguett and later versions showing an unrepentant woman giving as good as she gets as evidence that the dance was actually an empowering scenario for women.

Mistinguett at the Moulin Rouge. Wikimedia Commons

Ironically, the Apache achieved its greatest popularity as a show dance in revues and films; real Apaches preferred a straight tango or cakewalk. Interestingly, when you watch early films of the dance, the lifts, spins and throws would not look out of place in modern ballroom and Latin dancing, not to mention ice skating. The dance was soon taken up by theaters in New York, and in 1909 the first Apache Gala Ball was held in Paris. So began the glamorization of this criminal subculture, and dressing as a gigolette became the go-to shortcut to a stereotyped Parisienne at fancy dress parties.

The dance lived on long after the real Apaches had disappeared; in 1927 for example, a musical entitled ‘The Apache’ was staged in London. After the Second World War, it metamorphosed into the Java- different steps but still holding on to that raffish, edgy, slightly dangerous ambience that was associated with bohemian Paris.

The Apaches more or less disappeared with the First World War. As mainly young men (18-25 years old), they were prime conscription fodder and many lost their lives in the trenches. After the war, crime in France evolved into a new and much more organized underworld that made the Apaches look like the amateurs they basically were. But for around 20 years they terrorized the respectable people of Paris and entered the city’s folklore.

Lead photo credit : Meeting of Apaches and police officers on the Place de la Bastille. Credit: Gallica/Wikimedia Commons

More in Apache, culture, dance