Forbidden to Forbid – May ’68 in France (Part 2)

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

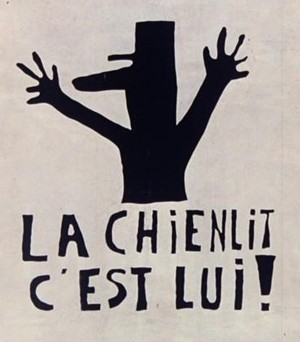

Le Chienlit, c’est lui (He’s the cause of havoc Poster by Ecole de Beaux Arts students, May 1968).

When the streets take to the theater

I was a student at the Sorbonne in May of 1968 and, though I didn’t participate directly in the student riots, I was lucky enough to be what you might call an “inside observer” when students called on the population to donate medicine and discovered that Kotex was an excellent tear-gas filter or, during the general strike, again occupied the school’s main amphitheatre and declared it to be an “autonomous people’s university”.

I was also there when, on May 15th, 2,500 of those same students stormed the Théâtre National, Odéon in the nearby St Germain district. That day theater manager Jean-Louis Barrault asked authorities what he should do and was told to “Open the doors and negotiate”. Barrault opened the doors, “negotiated” and the theater quickly became a twenty-four hour debate center, similar to what it must have been like living in Paris during the French Revolution of 1789.

I sat in the theater listening as heated debates shook the walls of a monument intended for less “down to earth” spectacles. The subjects of debate between those on the stage and those in the audience were more or less the same as those encountered in the street: liberalizing contraception, opening up the media, inventing new ideas, challenging authority, revamping the country’s historical perspectives, attacking class discrimination in education, all of the possible outcomes of the general strike and even the prospect of a possible military coup d’état.

Damage to the theater was inevitable; Barrault was eventually “thanked for his services” and fired. A courageous and wonderfully talented actor and director, along with his wife Madeleine Renaud, Barrault went on contributing profoundly to the progressive enrichment of French theatrical culture over the years that followed May ‘68, but independently and outside of “government” structures!

May 15th, 1968, occupation and debates, National Theater –Odéon

Is there a President in the Palace?

Two other outstanding moments mark May ’68 in my memory. One was the sudden disappearance of de Gaulle for two days on May 29th when the general strike continued despite what was to be called “the Grenelle agreement”. After postponing his Council of Ministers meeting and convinced that if he dissolved the Assembly his party would lose the elections to François Mitterrand and the Socialists, the General packed up his personal papers and announced that he was going to his country home in Colombey-les-Deux-Eglises. The presidential helicopter never arrived in Colombey and no-one, not even George Pompidou, de Gaulle’s Prime Minister, knew what was going on. Rumours spread that de Gaulle had fled the country and, with Paris surrounded by French Army tanks, it was feared that we were in for an eventual military “coup d’état”. Though it’s mute, you’ll get an excellent idea of what May ’68 felt like here. The video was taken on May 27th.

I was on an American passport and it was also rumoured that the Sorbonne would again be invested by State Police and all foreigners expulsed from the country. We were bussed to a “foyer de jeunes travailleurs“ (a sort of refuge for young working people) in the suburbs. Today we know that members of government at the Presidential Elysée Palace also panicked, burning papers and trying to find ways of fleeing the country where there was no gasoline, in the case of an eventual Revolution.

Alone to assume the direction, Prime Minister Pompidou soon discovered that De Gaulle had, in fact, “fled” to the French military base of Baden Baden in Germany to meet with a fellow general Jacques Massu. Former key figure in the efforts to keep Algeria from becoming independent during its war for independence, Massu eventually convinced de Gaulle that the French really needed his presence and he came back to Paris. We were all gathered around the radio and I remember feeling my knees knocking together in fright as we listened to de Gaulle’s speech before 30,000 people locked into the Charlety Stadium on May 30th. The tension was so high that I actually found my knees shaking. One though kept running through my head, “A single shot, a movement of panic, and the tanks placed all around Paris will move into action.”

There was no shot and though the sudden turnout of support was of short duration, a pro-Gaullist street march, up the Champs Elysées, that ensued was overwhelming. It was enough to allow De Gaulle to dissolve the National Assembly and win the June elections with 354 of the 487 seats, a first time ever record in parliamentary history.

The lasting effects of May ‘68

Graffiti covered the walls, not with gang insignias or tags, but with a poetry of metaphores. “C’est interdit d’interdire” (It’s forbidden to forbid). “Sous les pavés la plage” (Under the paving stones, the beach); traditionally a great many French people spend their summer vacations on the Mediterranean and Atlantic coast beaches. When the students snatched up the paving stones to build the barricades, they found a layer of sand beneath them). With reference to a toilet: “Veuillez laisser le Parti Communiste aussi net en sortant que vous voudriez le trouver en y entrant” (Please leave the Communist Party as clean when you leave it as you would like to find it upon entering). “L’imagination prend le pouvoir” (Imagination is seizing power). “Soyez réaliste, demandez l’impossible” (Be realistic, ask for the impossible). “La barricade ferme la rue mais ouvre la voie” (Barricades close off the street, but open the way). Or, finally, “Les murs ont la parole” (Walls have the right to speak).

The graffiti, like the posters made by Beaux Art students, including the response to the President’s comment to the Press “La réforme oui ; la chienlit non” (Reform yes, havoc no) were a response to governmental censorship of French media. Note that the term actually means “sh…in bed” and comes from a character in bedclothes with mustard on the back, long ago a part of the Paris carnival and parade.

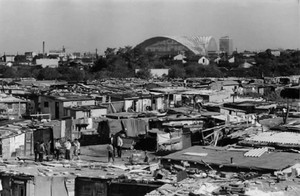

Shanty town in Nanterre in the ‘60s

On May 26th and 27th just before De Gaulle’s departure for Germany, Prime Minister George Pompidou and the French Ministry of Labor, located rue de Grenelle, drew up what was to be known as the 1968 “Grenelle agreement”,. The monthly minimum wage or SMIG (Salaire Minimum Interprofessionel Garanti) was increased by 35% and salaries by 10%. Summer vacations were also extended to four weeks. The agreement allowed workers themselves to set up local branch of any one of the five recognized trade unions within any company.

Though outside radio stations like Radio Luxembourg or Europe l existed since the 1950s, their content was heavily controlled. In response to a censor board restricting free expression in art, cinema, music, radio, TV and the press and the obligation for all media to submit what they intended to say for government approval, the ‘70s saw, among other deep seated changes, the creation of numerous “free radios” and satirical journals.

Large numbers of French-born Algerians or “pieds noirs” (black feet) had poured into the country at the end of the Algerian war in 1962 with no place to live. As was the case for other immigrants who worked, but couldn’t find lodging, one solution was an immense shanty town surrounding the Nanterre campus northwest of Paris. You’ll find a video here. The town reminded students at Nanterre, on a daily basis, of the reality of workers in France in 1968 and was directly responsible for their revolt. The major business district of La Défense now stands where tin huts stood when I arrived in Paris in 1965. In 1971 the University of Paris was divided into 13 new colleges. As for the Sorbonne, a rental service, allowing TV and movie studios to use the historical buildings as sets, was put into place to help pay for reparations resulting from the May ’68 events.

The contraceptive pill had become legal in 1967, but the Vatican still counted in French politics. The Women’s Liberation Movement and laws giving women the right to decide what they “did with their bodies” stemmed directly from May ’68, though any of these changes only really took form beginning in 1974 under Giscard d’Estaing, including legalizing of abortion in 1975.

Street march: The banner reads: “Workers Students United, We’ll win out”

Street march: The banner reads: “Workers Students United, We’ll win out”

What had begun in the north eastern suburb of Nanterre as a small student protest on January 8th with students forcing the Minister of Youth and Sports to leave the inauguration of a local swimming pool, officially lasted until April 28th, 1969 when, still President of the Republic, Charles De Gaulle announced that he intended to decentralize the hitherto Paris oriented power system and distribute it to regional governments. “If the response to a public referendum is affirmative, I’ll continue my mandate. If the vote is negative, I’ll step down.” The vote was “no” and former Prime Minister George Pompidou was officially elected President of the Republic on June 16th, 1969. De Gaulle retired to his home in Colombey-les-Deux-Eglises where he passed away from a stroke a year later on June 9th 1970, at the age of 80.

Information sources: Le Monde – Dossiers & Documents, number 264, Wikipédia mai ’68, Liinternaut mai ‘68

Photo credits:

Poster reprint from Wikipédia commons

Special thanks to Jean-Luc Besset at Live2times.com for permission to reprint the Odéon theater photo.

Student-workers protest march wikirouge.net

Nanterre Shanty town, Jean Pottier

More in French history, history