Kimonos and Kabuki in Paris: Two Visual Feasts

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

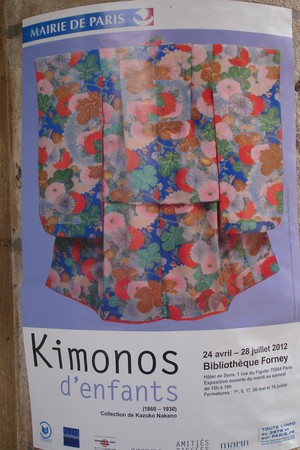

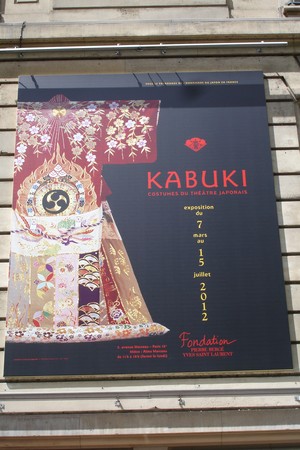

If you love sumptuous fabrics and are intrigued by Japanese culture, there are two exhibitions in Paris you should not miss. One is Kimonos d’Enfants 1860–1930 (“Children’s Kimonos 1860–1930”) at the Bibliothèque Forney, through July 28, and the other is Kabuki – Costumes du Théâtre Japonais (“Kabuki – Japanese Theatre Costumes”) at the Fondation Pierre Bergé – Yves Saint Laurent, through July 15. Not only do these exhibitions provide a most pleasing way to learn about Japanese fabrics, culture, history, and theatre, but they are also visual feasts.

If you love sumptuous fabrics and are intrigued by Japanese culture, there are two exhibitions in Paris you should not miss. One is Kimonos d’Enfants 1860–1930 (“Children’s Kimonos 1860–1930”) at the Bibliothèque Forney, through July 28, and the other is Kabuki – Costumes du Théâtre Japonais (“Kabuki – Japanese Theatre Costumes”) at the Fondation Pierre Bergé – Yves Saint Laurent, through July 15. Not only do these exhibitions provide a most pleasing way to learn about Japanese fabrics, culture, history, and theatre, but they are also visual feasts.

The more than 100 kimonos and related items displayed in “Kimonos d’Enfants 1860–1930” are from the private collection of Nakano Kazuko, and the catalog, which is in French, German, and English, contains touching reflections on how she came to lovingly collect them.

The word “kimono” is derived from the elision of two Japanese words, kiru, which means to wear, and mono, which means “thing,” so the word kirumono became, simply, kimono, or “thing to wear.” A kimono is made from seven pieces of clothe stitched together – two body panels, two sleeve sections, two front overlaps, and a collar. An adult kimono requires 12 meters of fabric, a child’s kimono much less. After an adult kimono was worn out, it might be recut to fit a child.

Although the wearing of kimonos is almost nonexistent in Japan today, except for special ceremonial or other occasions, the creation of children’s kimonos once expressed society’s values, but especially the deep sentiments of the mothers who created them. As the exhibition explains, “At a time when the life of a child was often short lived, families, and especially mothers, would transmit all of their care and love to their children through the clothing they had made for them, or that they themselves made by hand.”

Accordingly, fabrics were made with certain motifs that symbolized all the aspirations a mother might have for her child. Good luck motifs include pine trees, bamboo, and plum trees; long life motifs include cranes and tortoises. Other motifs include those representing good health, strength, kindness, intelligence, prosperity, and beauty. Motifs for girls include those wishing for a good marriage or fertility, or prosperity for the descendents, and for boys, they include motifs for a successful military career, success in social life, or wealth. To accommodate the body of a growing child, vertical pleats were sewn into the back of a kimono, which could be let out as the child grew.

Accordingly, fabrics were made with certain motifs that symbolized all the aspirations a mother might have for her child. Good luck motifs include pine trees, bamboo, and plum trees; long life motifs include cranes and tortoises. Other motifs include those representing good health, strength, kindness, intelligence, prosperity, and beauty. Motifs for girls include those wishing for a good marriage or fertility, or prosperity for the descendents, and for boys, they include motifs for a successful military career, success in social life, or wealth. To accommodate the body of a growing child, vertical pleats were sewn into the back of a kimono, which could be let out as the child grew.

Threads, called semamori, were often embroidered on the back of children’s kimonos because it was believed they served as a talisman against evil spirits. In addition, kimonos of children might resemble the designs and colors of kimonos for adults in the hope that evil spirits could not recognize them as children.

One kind of kimono was worn by newborn babies and was made by assembling pieces of fabric donated by various people in the hope that the virtues and good fortune of the donors would be transmitted to the newborn. The exhibition includes one such kimono made of 197 pieces of fabric from family members and friends.

Kimonos from families across the socioeconomic spectrum are included in the exhibition, so the pieces include both ornate painted and embroidered silks using elaborate dying and weaving techniques, and modest, unadorned fabrics. Those made of silk that were painted, embroidered, or both, were the most prestigious.

Although the wearing of kimonos has virtually disappeared from everyday life in Japan, their use is alive and well in kabuki theatre, as the exhibition, “Kabuki – Costumes du Théâtre Japonais,” vividly shows. This exhibition displays 30 kabuki costumes and a selection of accessories worn during kabuki performances, including swords, umbrellas, shoes, and fans, some of which are still in use. All are on loan from Shôchiku Costume in Tokyo, the Musée national des Art asiatiques – Guimet in Paris, and the Musée des Arts asiatiques in Nice.

Although, today, all the characters in a kabuki play are male, the genre was actually created by a female comedian, Izumo no Okuni, between 1597 and 1607, and all the roles were originally performed exclusively by women. Kabuki became an exclusively male endeavor in 1629.

The word kabuki is formed by a combination of three Japanese words – ka (chant), bu (dance), and ki (acting). Kabuki plays tell stories of tragic heroes, lovers reunited, noble and honorable samurai, and of simple, ordinary people. Because all the roles are played by men, the costumes help the audience differentiate the male and female roles. Kabuki costumes are often extravagant and sumptuous, and the personality and status of the character are revealed through the shape, colors, symbols, accessories, and makeup, which can also be extravagant.

The kabuki costumes exhibited here are made of elaborate fabrics in rich and luscious colors including lavender, red, pink, lime green, blues, and oranges. Motifs include floral patterns, falcons, leaping fire, clouds, cranes, musical instruments, snow-covered pines, and even an octopus with glaring eyes. There is much use of gold thread.

The kabuki costumes exhibited here are made of elaborate fabrics in rich and luscious colors including lavender, red, pink, lime green, blues, and oranges. Motifs include floral patterns, falcons, leaping fire, clouds, cranes, musical instruments, snow-covered pines, and even an octopus with glaring eyes. There is much use of gold thread.

An informative if somewhat dated English-language film on the history of kabuki is included in the exhibition, which explains the elements of this highly stylized traditional form of Japanese theatre, which often includes exaggerated gestures and a fierce battle scene, a traditional feature of the genre. The important role of wigmakers is also explained.

The exhibition also includes excellent footage of kabuki performances, which bring together all the elements discussed in the exhibition.

As with many traditional elements of many cultures, kabuki is on the decline. The number of performances and kabuki actors has dropped dramatically, and the Japanese government is supporting this 400-year-old theatrical tradition.

Whether kabuki becomes part of a disappearing culture and goes the way of the wearing of kimonos in everyday Japanese life remains to be seen. But these exhibitions provide a unique opportunity to learn about Japan through two emblematic elements of Japanese culture and society.

Bibliothèque Forney

Tel: 01 42 78 14 60

Hôtel de Sens

1, rue du Figuier, Paris 4th

Quai des Célestins

Metro: Pont Marie – Line 7; St-Paul – Line 1

Bus: 67

Open: Tues, Fri, and Sat 1pm–7:30pm

Wed and Thurs 10–7:30pm

Closed: Sun, Mon, and holidays

Entrance fee: 6 euros

Reduced fee 4 euros

Half fee: 3 euros

Email

Fondation Pierre Bergé – Yves Saint Laurent

Tel: 01 44 31 64 31

3 rue Léonce Reynaud, Paris16th

Metro: Alma Marceau – Line 9

Bus: 42, 63, 72, 80, 92

Exhibition space open to the public only during temporary exhibitions

Open: Tues–Sun 11am–6pm; last entrance 5:30pm

Closed: Jan 1, May 1, May 8, Aug 15, and Dec 25

Entrance fee: 7 euros

Reduced fee: 5 euros

Handicapped accessible

Visits to the Yves Saint Laurent studio can be arranged at Cultival

Reservations are required and fees start at 13.50 euros

Subscribe for FREE weekly newsletters.

BonjourParis has been a leading France travel and French lifestyle site since 1995.

Readers’ Favorites: Top 100 Books, imports & more at our Amazon store

We update our daily selections, including the newest available with an Amazon.com pre-release discount of 30% or more. Find them by starting here at the back of the Travel section, then work backwards page by page in sections that interest you.

Current favorites, including bestselling Roger&Gallet unisex fragrance Extra Vieielle Jean-Marie Farina….please click on an image for details.

Click on this banner to link to Amazon.com & your purchases support our site….merci!

More in exhibition, Exhibitions, fashion, French fashion, Paris exhibitions, Paris fashion