Film Review: Petite Nature

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

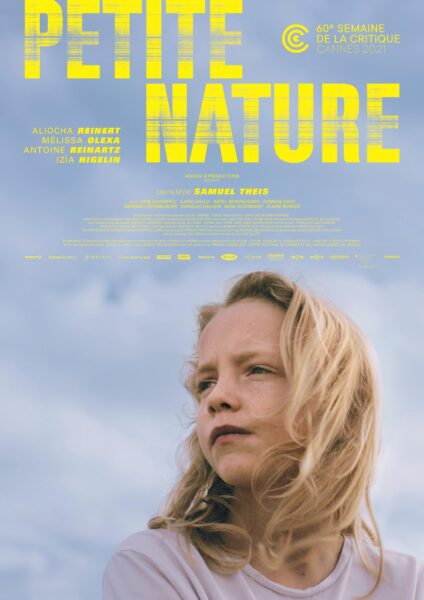

One of the things that makes Aliocha Reinert’s performance in Petite Nature so remarkable is that his face seems to contain the ostensible limitations of his character, 10-year-old Johnny: his slightly hangdog eyes and mouth evoke a poor boy destined for lower-class oblivion. But the twinkle that pops magically into those eyes, and the warm smile that blooms like a flower, give hints of more. He also has a subtle way of giving banal movements a grace that promises future mastery of some sort. A head of long blonde hair tops it off, expressing a sense of freedom, like a wild mustang’s mane, although it seems out of place in the hard-bitten world of the HLM (habitation à loyer modéré: low-rent housing) that is the film’s setting. Aliocha might be one of those kid actors who make an impression out of natural charisma, only to go nowhere when adolescence sets in. Or he might turn out to be like the child actress who made such an impact on child me as Joey in the sitcom Courtship of Eddy’s Father, and later became adult actress Jodie Foster. In the meantime, his stunning interpretation of Johnny is what carries Samuel Theis’s second feature.

Petite Nature is more or less une tranche de vie, a slice of life. It’s fascinating to observe this young boy get on with his life, tend to his wreck of a mother, and take care of a younger sister to boot. The film resembles the “human interest” social films of Ken Loach or Luc Dardenne, but more broadly Theis takes us into a part of Lorraine, in eastern France, that many don’t know (or care about). It’s near the German border, and the mother, Sonia, like others in the area, works in Germany, as a cashier in a cigarette shop. Many speak Plattdeutsch, the thicker, looser dialect of German. The biggest town is Metz, where you have not only institutions of higher learning (my son attended an engineering school there) but also a branch of the Pompidou Center. The director shows us how the Metz center brings culture to the region and also attracts educated types who then ironically contribute to the class divide.

Theis directs with impressive assurance — much of that is due to the fact that he’s from the region; even so it’s hard to believe Petite Nature is his second feature. But then the film lurches from tranche de vie to what the French call misérabilisme, wallowing in poverty. Sonia has to survive as a single mother in a forbidding HLM on a small salary. But why is the apartment such a pig sty? Sonia is poor and rough around the edges, but she does have a job, is presumably subject to German rigor, and has her son to help out. Such residences are often ramshackle, but the family flat looks too much like a production designer’s dump. Likewise, the bit players depicting Sonia’s friends seem to be theatrically performing their version of po’ folk.

A still from “Petite Nature” showing actors Aliocha Reinert and Mélissa Olexa

As Sonia, Mélissa Olexa is attractive and intense, and on a certain level very authentic. Considering that she’s a non-professional originally from Metz, she’s almost as astonishingly impressive as Aliocha. But I was troubled by her performance. That’s just it: as with the secondary roles, she seems too performative, a bit like Marion Cotillard when she belts out her roles. I’ve known persons like Sonia, and while they can be primeval forces of nature in extreme situations, they’re not always that way. There’s emotional downtime, when they’re as normal as anyone else. Even Sonia’s downtime, as when she’s having her tired feet massaged by Johnny, seems performative.

Antoine Reinartz at the Césars in 2018. Photo credit: Georges Biard/ Wikimedia Commons

Since his mother’s rather too much, it’s not surprising when Johnny bonds with a teacher, Monsieur Adamski, sympathetically played by Antoine Reinartz, who takes an interest in him. He sees Johnny’s untapped talents, in addition to his raw intelligence and sweet humanity. Adamski is himself intelligent, warm, compassionate, one of those teachers who turn a difficult job into a vocation molding young pupils. This is an old tradition in film — Sidney Poitier’s passing brought back memories of his compassionate turn in To Sir, With Love. Jon Voigt also played a young teacher in underprivileged surroundings in Conrack. More recently there was the French film, Entre Les Murs (The Class). Adamski and his companion take to inviting Johnny to events such as a private evening at the Centre Pompidou Metz. Sonia is too self-absorbed to pay much attention, though she puts the teacher on guard against raising unrealistic hopes in her son that will be dashed against the rocks of disappointment. (We wonder if that’s precisely what happened to her.)

Petite Nature

The emotional triangle of Johnny, his mother and teacher, is engrossing, and becomes more so as it’s transected by the gradually developing line of the boy’s ambition to make something of himself, to escape his environment … including his mother. Mr. Adamski offers him the possibility of studying in an elite Metz boarding school. This seems to be the essential drama of the film, but instead the director takes another lurch, into LGBTQ territory.

We’re asked to believe that a pre-pubescent would suddenly hit on his (unreceptive) teacher in a sexual way, but we’ve had no inkling of any sexuality at all in Johnny (while Adamski lives with his girlfriend). We don’t want be like Queen Victoria, who wouldn’t sign a provision of an anti-homosexual bill referencing lesbianism because she refused to believe such a thing could exist. I’ve seen (and reviewed) good features and documentaries on gay and trans young people. But nothing in Petite Nature prepares us for this, except … the hair. That was the clue planted by the director. Sorry, Mr. Theis, that don’t cut it. Anything is possible (Theis has said the film is autobiographical), but as regards Johnny, I didn’t believe it for a second.

The director indulges in a few meretricious scenes, attracted by the pull of melodrama on one hand and political correctness on the other (and maybe the influence of the Canadian director Xavier Dolan). Fortunately, he resolves this in decidedly unmelodramatic fashion, and the film returns to a more even, and authentic, keel. A scene in church, depicting Johnny’s first communion, is another interesting look at the local culture, and unwittingly leads to the film’s conclusion, and Johnny’s new beginning. It’s a fitting end for a film that, despite its imperfections, combines a talented director and extraordinary cast to create a powerful vision of life in one corner of France.

Production: Avenue B Productions/France 3 Cinéma

Distribution: Ad Vitam Distribution

Lead photo credit : Petite Nature. © 2021/ Semaine de la Critique

More in cinema, film review, French film