Amour the movie: How French Is It?

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

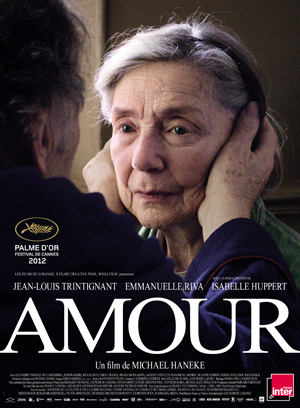

Amour was one of the best films of 2012, and was universally praised (garnering at least 16 Best Film awards). But how French is this film? By the normal standards for obtaining subsidies or award nominations it qualifies for French status easily enough: it’s in the French language, has a French producer, was shot in France. It stars two of the French cinema’s great icons, Jean-Louis Trintignant (Belle de Jour and many more) and Emmanuelle Riva (Hiroshima Mon Amour), as an elderly couple stricken by the wife’s infirmity.

Amour was one of the best films of 2012, and was universally praised (garnering at least 16 Best Film awards). But how French is this film? By the normal standards for obtaining subsidies or award nominations it qualifies for French status easily enough: it’s in the French language, has a French producer, was shot in France. It stars two of the French cinema’s great icons, Jean-Louis Trintignant (Belle de Jour and many more) and Emmanuelle Riva (Hiroshima Mon Amour), as an elderly couple stricken by the wife’s infirmity.

But the director and writer of the film, or as they say here, the auteur, isn’t French at all. Michael Haneke has made several French productions, but he’s actually Austrian. Most of his films have been in German, and take place in Austria or (like The White Ribbon) Germany. All express a dark, chilly vision of existence, and Amour is no exception. It describes the life of Georges and Anne, two bourgeois Parisians now in their 80s. They are well-to-do, educated, and cultivated (Anne was a high-level music teacher, one of her protégés a star pianist). What’s more they love each other deeply after decades of marriage.

One day, Anne suffers a trancelike seizure. When she goes to the hospital we learn that she has some sort of obstruction in a blood vessel. Instead of being cured by France’s second-to-none medical system, her health collapses. (This isn’t very clear, but something similar happened to a friend of mine.) We suppose she’s the victim of a debilitating stroke, but the fact of being hospitalized also seems to demolish her sense of personhood.

Georges does his utmost to take care of Anne at home. He cooks for her, bathes her, helps her in the bathroom, medicates her. But his wife’s condition continues to deteriorate and wears on him, making him grimly determined and unpleasant to be around. Haneke films this descent with an immaculate and relentless style. The shots are meticulously composed, the progression of scenes like a set of gears in an unforgiving machine.

Georges does his utmost to take care of Anne at home. He cooks for her, bathes her, helps her in the bathroom, medicates her. But his wife’s condition continues to deteriorate and wears on him, making him grimly determined and unpleasant to be around. Haneke films this descent with an immaculate and relentless style. The shots are meticulously composed, the progression of scenes like a set of gears in an unforgiving machine.

This clinical style isn’t very French, but further north there are diverse associations: New Objectivist painting, writers like Thomas Bernhardt, Herman Broch, Karl Kraus. Haneke’s vision may be metaphysical, with deep things to say (most of them nasty) about one corner of the human condition. But like other German and Austrian artists, he also has a very social side. Amour is corrosive about the bourgeois lifestyle: the enormous apartment becomes a giant tomb, the paid help are in it for the money, even culture seems empty—classical music, by whatever composer, sounds like a dirge.

On one hand, we identify with the wife’s pain, humiliation, her fright at what her husband must put himself through. We also feel for the husband’s mounting helplessness in the face of mortality. Their love for one another is moving, and even evokes softer films, like On Golden Pond. But Anne also seems inhumanly dignified and Georges unbearably controlling. The haut-bourgeois couple find it impossible to lower themselves by asking their daughter (a first-rate Isabelle Huppert) for help, or seeking institutional care.

It might seem tender-minded and maudlin to ask for more “uplifting” moments in a film with such a harsh subject. Haneke does provide a few, as when Anne struggles through her loss of speech to recount an old romantic memory. Then we think that it would have been more realistic to include more such scenes. In terms of filming, Haneke’s direction has austere integrity imprinted all over it. A scene in which a pigeon flies into the apartment brings a touch of mystery and lightness—but it’s so deliberate that it calls into question the rest of the movie’s implacable bleakness.

It might seem tender-minded and maudlin to ask for more “uplifting” moments in a film with such a harsh subject. Haneke does provide a few, as when Anne struggles through her loss of speech to recount an old romantic memory. Then we think that it would have been more realistic to include more such scenes. In terms of filming, Haneke’s direction has austere integrity imprinted all over it. A scene in which a pigeon flies into the apartment brings a touch of mystery and lightness—but it’s so deliberate that it calls into question the rest of the movie’s implacable bleakness.

For all of that, Haneke knows how to tell a story. The opening shot presents a mystery, or at least a question, that we wonder about throughout Amour. The end will bring us full circle: the stark northern story fulfils the French taste for symmetry. Perhaps this is the face of European film to come: visions and sensibilities from different countries interacting. There are other hints of Europeanization: Eva’s husband is a Brit, and there’s a brief exchange in English, the concierge and his wife are Spanish or Portuguese, the uncaring caregiver is East European, the musical protégé is going to perform in London.

Some of Michael Haneke’s earlier films seemed meretricious and lurid. The White Ribbon made a believer out of many, and Amour is another achievement. Counterbalancing the dark view of the afflictions of old age is the fact that this film was made by a director past seventy, and that the stars are as aged as their characters, but give the best performances of their careers. Still, however many honors the film earns, Marcel Pagnol it ain’t.

Production: Les Films du Losange (with X Films, Wega Film)

Distribution: Les Films du Losange (France)

More in Amour, film review, French film