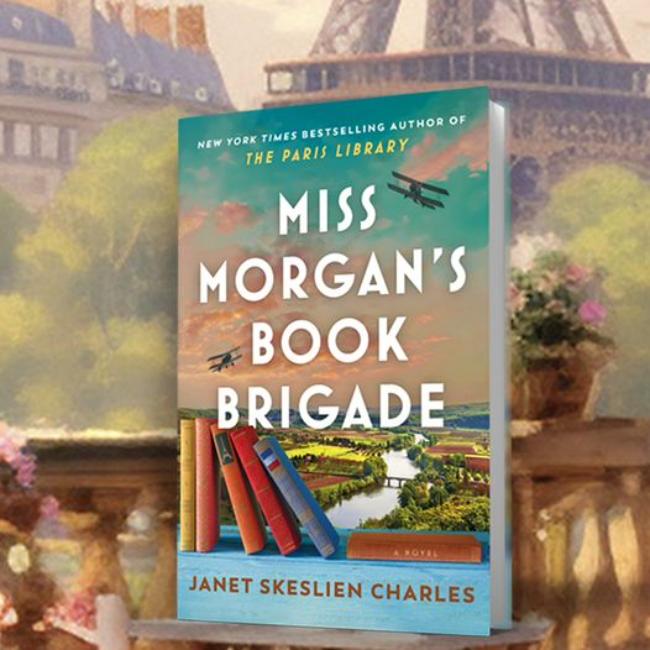

Interview with Janet Skeslien Charles

Janet Skeslien Charles is the New York Times and #1 international bestselling author of The Paris Library, a historical novel that highlights the history of the heroic librarians in Paris during the Nazi Occupation. The second novel in her library trilogy, Miss Morgan’s Book Brigade, explores the little-known story of the American Committee for Devastated France, which was founded by Anne Morgan. After an extensive, whirlwind book tour in the United States, the author is back home in Paris, continuing to promote her book. She graciously took the time recently to answer Janet Hulstrand’s questions about Miss Morgan.

JH: Congratulations on the publication of Miss Morgan’s Book Brigade! I understand that this book was about 10 years in the making — true? Do you want to tell our readers just briefly what drew you to this story? How did you learn about the real-life Jessie Carson, and what made you want to tell her story?

JSC: Thank you! I came across the idea for this book when I was researching Dorothy Reeder, the librarian who stood up to the Nazis in The Paris Library. Digging around the American Library Association archives, I discovered that in 1918, during the Great War, an elusive librarian named Jessie “Kit” Carson traveled to France, where she created something that did not yet exist here – children’s libraries. After the war, she transformed ambulances into bookmobiles. You can see why a booklover like me would be obsessed.

I researched both books at the same time, and when I hit a dead-end with one, I turned to the other.

JH: I’ve noticed that the book seems to have two titles — one for the U.S., and another — The Librarians of Rue de Picardie — for the U.K. edition, and maybe for other editions as well. Is there an interesting story behind this?

JSC: Yes, there are two titles. My agent, editor, and I brainstormed over 50 titles, from The Library Card to The Wild West Library School. The Morgan name means more in America, which is why that title stuck there. The editor who proposed the U.K. title wanted to show that the book takes place in France, without using the word France.

JH: One of the interesting things I learned in reading this book is just how much, and for how long, northern France suffered during the First World War — not just the soldiers in the trenches, but the civilian population as well. I think most people, when they hear the words “occupation of France” think of the Nazi Occupation during World War II, but this was a long-lasting occupation as well, right?

JSC: Like you, one of the most surprising things I learned while researching the book was the occupation of northern France by German forces. As you say, we learn about the Occupation during World War II but not during the Great War. Unfortunately, in the north at that time, most able-bodied Frenchmen were either in the army, prisoners of war, or dead. Some northerners fled, but for three long years, the women, children, and old men who remained were enslaved and half-starved. German soldiers were billeted in the homes of these French families, making for a painful cohabitation.

This goes back to that interview that you did with Emily Monaco on “Navigating the French,” and how the word “correct” in English and French has a different meaning. In that interview you mentioned that the word “correct” in French is about behavior and the right way to do something, rather than factualness. While researching The Paris Library, I interviewed and read memoirs written by Frenchwomen in Paris during World War II. Several times, these Parisiennes said that the Germans remained “correct.” They didn’t mean the Germans were right, they meant that the Germans behaved properly. This confused me until I read about the occupation of the north.

Ruins of Arras in April 1917. Photo: John Warwick Brooke / Public domain

In 1918, when Allied forces were finally able to drive back the enemy, the retreating German soldiers cut down trees in orchards and blew up bridges, seeded fields with landmines, and burned down hospitals and schools. In homes where they’d lived, soldiers smashed plates and wine glasses, sawed off the legs of chairs, and ripped apart books. They cut up family portraits. The destruction was personal. I think that the Nazi officers in Paris during World War II were soldiers in World War I. And in the capital, at least, they did not want a repeat of this destruction.

Ninety percent of the region of Picardie was demolished. CARD president Anne Murray Dike noted, “You can travel in a motor going forward in a straight line for fifteen hours and see nothing but ruins.”

CARD is the acronym for the aid organization Le comité américain pour les régions dévastées. Their headquarters was just 40 miles from the front, in a crumbling 17th century chateau that is now the only Franco-American Museum in the world. I highly recommend visiting it.

The Franco-American Museum at Blérancourt

JH: What was the most surprising thing you learned when doing the research for this book?

JSC: It was definitely learning about the Red Zone, an area defined just after the war as “completely devastated. Damage to properties: 100%. Damage to agriculture: 100%. Impossible to clean. Human life impossible.”

Covering 460 square miles, it is deemed too damaged (from elements such as lead and arsenic) for human habitation. Authorities estimate that if they continue working at the current rate, it could take another 300 years to clean up.

JH: What was the biggest challenge in writing this book? What was the greatest joy?

JSC: My greatest joy was learning about these amazing women. I loved the friendships and the exchange of knowledge between them. The Frenchwomen learned from the Americans and Englishwomen, the Americans learned from the French and the English – and when they returned home, the women shared what they learned. Mary Breckinridge created the first comprehensive healthcare system in America, based on what she had learned in France.

My greatest challenge was putting words in the mouth of my character, a real-life librarian. Jessie Carson did not leave behind letters housed in family archives like Anne Morgan and Mary Breckinridge did. I pieced together her personality by reading newspaper articles about her, reports she wrote, and memoirs of other volunteers who wrote about her. I hope that I did her justice.

Anne Morgan and Anne Murray Dike, ca. 1915. Unknown author. Public domain.

JH: You’ve just returned from a nine-city book tour in the US. I was interested to see that you did not include only large cities on your tour —you made at least a few stops in places that are probably not on the typical book tour. How were the locations for the book tour chosen? And what kind of response did you get along the way? I’ll bet people in some of those places were really thrilled to have you.

JSC: I loved being on tour! It was great to see so many readers. For The Paris Library, I did 200 events, mainly online, because the book came out during Covid. For this tour, my publicist worked with bookstores to set up the tour. I’d done online events with these bookstores during Covid, so it was great to connect with the booksellers in person.

JH: It was interesting to learn that one of the biggest impacts Jessie Carson had due to her work in northern France during the war was a major change in the reach of French libraries, which prior to that time did not include outreach to children. Can you tell us a bit more about that?

JSC: Here is how French writer André Chevrillon described the situation: “One must not think the American Committee introduced public libraries in France. There are some in cities and villages. But they do not meet the needs of the community; they are incomplete and badly organized; most are in small rooms, badly kept, and poorly lit. Readers are forbidden free access to the shelves. Entrance is prohibited to the reader, who is invited to stand behind a railing. The public can only make the choice of a book by consulting a dirty, torn catalogue. Librarians are clerks with no professional training and who are so overworked that they can bring but little vitality and interest.”

When Jessie Carson arrived in France, there were no female librarians and no libraries for the public. Rich people had private libraries, and universities had libraries for their (mostly) male scholars. There were no libraries for children and the working class. Jessie Carson created libraries for all.

There were a handful of French male librarians who wanted better libraries for all, but they were unable to fight the endless bureaucracy and unable to get funding. Jessie Carson created a library in the north of France, and Anne Morgan invited French politicians to visit it. Not many people said no to Anne Morgan. Once the French bureaucrats from Paris saw the possibilities, they were willing to fund public libraries.

JH: What conclusions would you like your readers to draw from this story, especially about the role of libraries in civic life? Are any of the issues that were alive in France in World War I still alive today in the United States?

JSC: Libraries are still in danger. Jessie Carson faced censorship from the church. She did not let the bishop control her collection. Today, librarians receive cut-and-pasted demands to take books off of shelves. The internet makes it easy for a small group of people to email thousands of demands to take books deemed “dangerous” off of shelves.

I hope that readers of my novels will conclude that our libraries, one of the rare places we can go and not spend money, are worth protecting. We need to protect our libraries and our librarians.

JH: I know you’re very busy still promoting Miss Morgan’s Book Brigade, but what’s next for you? Do you already have your next book underway, or at least a thought about what it will be? Or is it too soon to ask you that?

JSC: I’m currently working on the final installment of my library trilogy and having a lot of fun with it. The book is set in Paris during the 1990s.

Lead photo credit : JSC photo credit Eddy Charles

More in Anne Morgan, book review, books, Interview, Janet Skeslien Charles, Reading