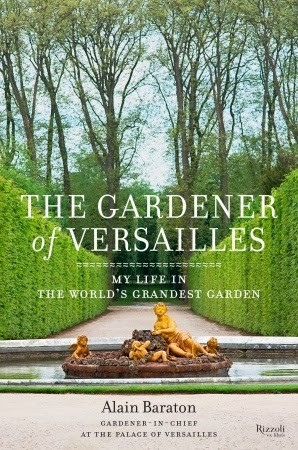

The Gardener of Versailles: My Life in the World’s Grandest Garden (A Book by Alain Baraton)

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

On December 26, 1999, a storm tore violently across France. Fifteen years later, le Tempête is still spoken of in hushed tones and nearly audible capitals. In the gardens of Versailles alone, 18,000 trees were lost, felled by the storm or so damaged they had to be cut down. So opens Alain Baraton’s book, The Gardener of Versailles: My Life in the World’s Grandest Garden, to a scene he describes as “a cross between a logging camp and an elephant graveyard.”

On December 26, 1999, a storm tore violently across France. Fifteen years later, le Tempête is still spoken of in hushed tones and nearly audible capitals. In the gardens of Versailles alone, 18,000 trees were lost, felled by the storm or so damaged they had to be cut down. So opens Alain Baraton’s book, The Gardener of Versailles: My Life in the World’s Grandest Garden, to a scene he describes as “a cross between a logging camp and an elephant graveyard.”

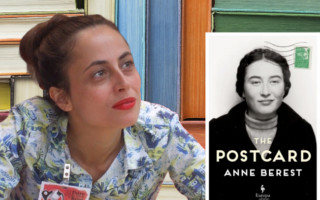

Serendipity results in the most interesting careers, and Baraton’s is no exception. He became a gardener to pay for his first camera and stayed on in this “place where the unexpected, and even the extraordinary, can happen at any moment.” He came to feel that his true family was at Versailles in “the gardens who have made me who I am.” In 1982, he became gardener-in-chief at the Château de Versailles, the youngest ever to hold that post.

Baraton shares the memories of more than 40 years of living and working in the gardens. He is an engaging raconteur who tells his story with humility and a delightful sense of humor. He chooses his words to convey his passion and his personality. To read them is to have him in the room, where he entertains you without your having to reciprocate. In this case, though, that’s cause for regret. I think he would be the sort of house guest one hates to see depart.

Versailles is a domain where majesty and intimacy coexist, of places where the royals displayed themselves and of places where they sought solitude. Baraton tells of its human side, of those who have left their mark, from his colorful coworkers to the youthful triumvirate of 17th-century decorative arts whose masterpiece it is – Le Vau, Le Brun and Le Nôtre, fresh from Vaux-le-Vicomte where their work had caught Louis’s eye and brought down a minister.

His sympathies lie with Marie-Antoinette, who represents to him the feminine side of Versailles. For a young princess under constant scrutiny, perhaps the ultimate luxury was to be found in solitude and simplicity, as seen in the Hameau de la Reine. He is less sympathetic toward Louis XIV, who sought to dominate nature as he dominated all. Louis remains an enigma, as his only writings are of his gardens.

In a discussion of French gardens, it is likely that the first name to come to mind is that of André Le Nôtre. The descendant of a long line of gardeners, he wanted to become a painter and had studied with Simon Vouet. As a gardener, Le Nôtre enjoyed a succession of dream clients who imposed no budgetary, aesthetic or time constraints. His style was born at Vaux and perfected at Versailles. Unfortunately for us, Le Nôtre left no writings.

While Baraton expresses a distant admiration as he acknowledges every gardener’s debt to Le Nôtre, he reserves his affection and esteem for Jean-Baptiste de La Quintinie, creator of the Potager du roi. This lawyer and scholar turned gardener has left us a book detailing his studies and experiments, something Baraton considers “the best legacy there is.”

While Baraton expresses a distant admiration as he acknowledges every gardener’s debt to Le Nôtre, he reserves his affection and esteem for Jean-Baptiste de La Quintinie, creator of the Potager du roi. This lawyer and scholar turned gardener has left us a book detailing his studies and experiments, something Baraton considers “the best legacy there is.”

It should be noted that Baraton himself has left us several books, of which The Gardener of Versailles is the first to be translated into English. Now that he has been introduced to English readers, I suspect it won’t be the last. (Compliments are due to Chris Murray for his fluid translation that transmits not only the author’s story, but his voice.)

If education is the key to conservation, Baraton is doing a monumental job of raising public awareness. His world is one where plants make us better people and trees bear silent witness to the cycle of life. It is a world where plants, and not music, soothe the savage breast. He speaks nostalgically of the changes that have occurred during his tenure at the gardens and argues persuasively that technology doesn’t necessarily equal progress. In today’s Versailles, where concerns of security and economy reign, one can understand if he yearns for a simpler time, one where bygone gardeners signed their work by burying messages in bottles.

Whether you enjoy reading of history or gardening or simply take pleasure in the memoir of someone who is passionate about his craft and finds gratification therein, I strongly recommend The Gardener of Versailles: My Life in the World’s Grandest Garden. There is an undeniable sweetness to be found in being in sync with nature and in dancing to the rhythm of the seasons. Baraton tells us that, distilled to its essence, what makes a good gardener is joy. I have a feeling he is a very good gardener. He ranks high on a list of people I’d like to meet – ideally, on his turf.

Images: Alan Baraton – Supermat; Hameau de la Reine – Simdaperce

Jane del Monte lived for a number of years in Paris. She is the owner of ARTS in PARIS, personalized tours that focus on French culture and l’art de vivre. The next tour, Impressions of Paris 2014, will take place in May.

More in book, book review, Paris book reviews