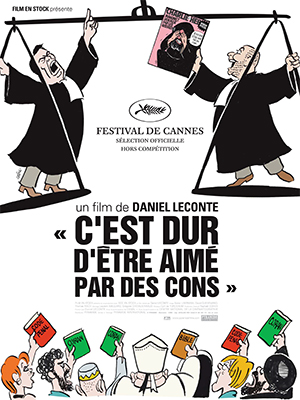

C’est Dur d’Etre Aimé Par des Cons (It’s Hard to Be Loved By Morons): A Look Back at Charlie Hebdo

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Daniel Leconte’s documentary about the trial of Charlie Hebdo for disseminating racial hatred was made in 2008 (a year after the trial), but was re-released after the terrorist attacks which decimated its editorial staff. Both the trial and the attacks stemmed from caricatures of the Prophet Mohammed that the satirical newspaper ran on its cover. This reviewer decided to see the film in the newly refurbished Louxor cinema, an old movie palace done up in faux-Egyptian décor. If that wasn’t ironic enough, the cinema is located in Paris’ Barbès-Rochechouart neighborhood, heavily populated by North African immigrants. I had my bag searched, and wondered defensively, as a dark-haired, dark-eyed person, whether the search policy applied to everyone or only a select un-French-looking few. The question turned out to be moot: there wasn’t a single minority person in the theatre.

Daniel Leconte’s documentary about the trial of Charlie Hebdo for disseminating racial hatred was made in 2008 (a year after the trial), but was re-released after the terrorist attacks which decimated its editorial staff. Both the trial and the attacks stemmed from caricatures of the Prophet Mohammed that the satirical newspaper ran on its cover. This reviewer decided to see the film in the newly refurbished Louxor cinema, an old movie palace done up in faux-Egyptian décor. If that wasn’t ironic enough, the cinema is located in Paris’ Barbès-Rochechouart neighborhood, heavily populated by North African immigrants. I had my bag searched, and wondered defensively, as a dark-haired, dark-eyed person, whether the search policy applied to everyone or only a select un-French-looking few. The question turned out to be moot: there wasn’t a single minority person in the theatre.

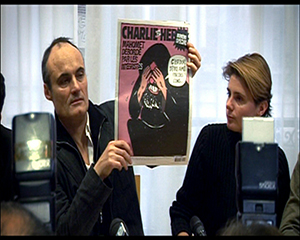

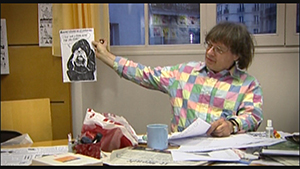

The documentary is enjoyable and well-made in a traditional way. There are talking-heads sequences of persons involved in the trial; scenes shot in the courtroom; scenes of protestors and counter-protestors outside the Palais de Justice; and images of caricatures of the trial (rather soft-core) drawn by Charlie Hebdo cartoonists. There are also views of editorial meetings at the newspaper. To provide narrative suspense, sections are titled Two Days Before the Trial, One Day Before, etc. The action is lively, with vociferous debates and outbursts, but there’s a sorrowful undertow as we see interviews of people who were recently murdered.

There’s not much surprising in the film, except a bizarre moment when personal animosity erupts between two opposing lawyers. The very French lawyer for the Muslim parties suing Charlie Hebdo makes a moving plea about colonialism and post-colonialism, linking these to present-day racism. This was taken personally by a female Charlie Hebdo lawyer, who threatened a defamation suit. The first lawyer then made over-the-top remarks about the second lawyer. Was this just emotional overflow from the trial, or was there something else going on that the audience isn’t privy to? Any number of lawyer jokes came to mind.

There’s not much surprising in the film, except a bizarre moment when personal animosity erupts between two opposing lawyers. The very French lawyer for the Muslim parties suing Charlie Hebdo makes a moving plea about colonialism and post-colonialism, linking these to present-day racism. This was taken personally by a female Charlie Hebdo lawyer, who threatened a defamation suit. The first lawyer then made over-the-top remarks about the second lawyer. Was this just emotional overflow from the trial, or was there something else going on that the audience isn’t privy to? Any number of lawyer jokes came to mind.

The portrait of Dalil Boubakeur, the establishment leader of French Muslims, is also intriguing. Boubakeur comes off as a personable figure able to empathize with his secular counterparts. He seems like someone who might have been able to broker some sort of moral consensus. But then we see the elderly leader’s filmed interactions brusquely stopped by his bodyguards.

The trial itself is jarring. The rule of law would seem to demand that the relevant statutes be argued by legal experts. Instead the trial turned into a media circus and political forum, with politicians and other personalities weighing in. At one point Francis Szpiner, the lawyer leading the case against Charlie Hebdo, complains that the trial has degenerated into a matter of who has enlisted the biggest names—indeed, the defense manages to get Nicolas Sarkozy (via a long letter) and then-Socialist leader François Hollande. In the end there is no decision delivered by either judge or jury. Instead, a prosecutor, seeming very satisfied with herself, peremptorily decides to drop the proceedings.

The debate about freedom of expression and hate speech is comprehensive, but skewed—just as it’s been in the wake of the attacks. Voltaire claimed he might detest what you said but defend your right to say it. Many in the film—lawyers, journalists, intellectuals—loudly proclaim the liberty to express what they agree or sympathize with, while what they detest brings forth rationalizations for different treatment. Claude Lanzmann (director of Shoah) makes the distinction between attacking beliefs and demographic groups, forgetting that abstractions are incarnated by human beings, and groups also represent beliefs and values.

The debate about freedom of expression and hate speech is comprehensive, but skewed—just as it’s been in the wake of the attacks. Voltaire claimed he might detest what you said but defend your right to say it. Many in the film—lawyers, journalists, intellectuals—loudly proclaim the liberty to express what they agree or sympathize with, while what they detest brings forth rationalizations for different treatment. Claude Lanzmann (director of Shoah) makes the distinction between attacking beliefs and demographic groups, forgetting that abstractions are incarnated by human beings, and groups also represent beliefs and values.

The few individuals in the film who defend liberty for everyone are set up as straw dogs: the publicity-seeking comedian Dieudonné (who was recently taken into police custody because of a tweet), and a Catholic priest who dares hold the German philosopher Jurgen Habermas in higher esteem than Charlie Hebdo. The intellectual debate has no real resolution, but that minority youth in the banlieues will find a double standard hypocritical and unfair is a fact.

The most powerful sequences in the documentary are those of North Africans, most of who are upset at the caricatures, but also progressive activists, particularly from Algeria, where a bloody Islamist insurgency was still a recent, searing memory. One woman shouts that she is “just as French as you are.” A man repeats over and over, half-hysterically, that his father died for France (and is grabbed by the police). Most chillingly, a young man, apparently an Islamist judging by his clothes and chin whiskers, concludes an angry diatribe with “You’ll see.” We certainly have.

The most powerful sequences in the documentary are those of North Africans, most of who are upset at the caricatures, but also progressive activists, particularly from Algeria, where a bloody Islamist insurgency was still a recent, searing memory. One woman shouts that she is “just as French as you are.” A man repeats over and over, half-hysterically, that his father died for France (and is grabbed by the police). Most chillingly, a young man, apparently an Islamist judging by his clothes and chin whiskers, concludes an angry diatribe with “You’ll see.” We certainly have.

Like any intelligent documentary, It’s Hard to be Loved makes the viewer think, and for some, remember. I used to be a regular Charlie Hebdo reader, then stopped, finding its humor puerile, even before the vogue for Prophet caricatures. I wasn’t alone—the newspaper had a circulation of only 30,000. Still, I marched with many others to support “the right to be shocked.” I was shocked early one morning to see people lined up before a newspaper kiosk, waiting to buy their post-attack Charlie. Apparently 3,000,000 copies will be printed. How many will be sold in France’s simmering suburbs?

Production: Films en Stock/Canal Plus

Distribution: Pyramide International

More in Charlie Hebdo, film review, French film