Mirror

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Of course I’ve known this for years, but it suddenly hits me. Jean-Claude, the waiter who always brings me my wine or coffee no matter where I sit in his café, is the son of Bernard, the first waiter who served me my wine or coffee here many years ago. It’s a strange little dance we do, Jean-Claude and I. I am not a regular, going sometimes nearly a year—once, I think, three years—without stopping for a drink or a meal. Yet whenever I walk in and sit myself down, Jean-Claude is immediately there, shaking my hand, addressing me by name, asking after business as if I’d been in only last week, and bringing me up to date with him. Bernard is still alive and lives with Jean-Claude and his family in a house in Asnières north of Paris. Together, they bought an interest in the café about thirty years ago and the rest a few years later and business is always good—with a shrug, of course—but good. If I have a second glass of wine, it’s on the house without fail.

Of course I’ve known this for years, but it suddenly hits me. Jean-Claude, the waiter who always brings me my wine or coffee no matter where I sit in his café, is the son of Bernard, the first waiter who served me my wine or coffee here many years ago. It’s a strange little dance we do, Jean-Claude and I. I am not a regular, going sometimes nearly a year—once, I think, three years—without stopping for a drink or a meal. Yet whenever I walk in and sit myself down, Jean-Claude is immediately there, shaking my hand, addressing me by name, asking after business as if I’d been in only last week, and bringing me up to date with him. Bernard is still alive and lives with Jean-Claude and his family in a house in Asnières north of Paris. Together, they bought an interest in the café about thirty years ago and the rest a few years later and business is always good—with a shrug, of course—but good. If I have a second glass of wine, it’s on the house without fail.

Jean-Claude is pleasant and friendly with all his customers, but his treatment of me is special, somehow, and I’ve never completely figured it out beyond thinking it must have to do with continuity. I started coming here when he was still, I think, in école primaire, fifth or sixth grade. I met him then or possibly a year later one day when he was tagging after Bernard, and his father wanted me to meet him because Jean-Claude was studying English and doing very well. Prompted carefully, he stuck out his hand and said, “A pleasure to meet you, sir.” I asked if he’d be kind enough to join me, told Jean-Claude to ask the waiter for “a hot chocolate for my pal and me,” which Bernard brought quickly and with a great deal of formality though I thought he’d split a gut trying not to laugh, and then I taught Jean-Claude every dirty word I could think of in English: he may be the only middle-aged Parisian who knows what LAMF means. After the lycée, he went into the army, studied at a hotel and restaurant school, then came to work in the café alongside his father. As far as I know, he is the businessman in the family and probably figured out the advantages and pitfalls of buying the place, but he still likes to wait on tables—all to the good, since meals fly out of the kitchen for his customers.

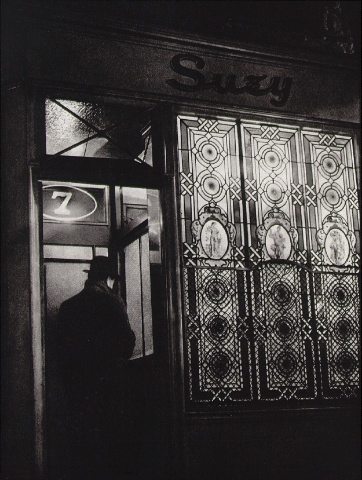

Jean-Claude is my metaphor for the qualities of Paris that I like. The welcome is sincere and pleased, but the expectations are not exorbitant: there is an understanding that you belong to yourself, not to the city or his café, and have a life of your own other than providing yet another extra for the street scene or the restaurant interior—that you’re not an apple or a ham in a still life. After his greeting today, he does what he always does which is to leave me alone, and that’s all to the good too because I’m a little down and need to figure out why. I get nowhere with these thoughts, write a little in my spiral notebook, then look into the large mirror at a slight angle to my table and catch sight of another client, sitting alone like me. He’s looking around at nothing in particular, maybe trying to find something or someone interesting to speculate about, his left arm draped over an empty chair, his sunglasses toward the end of his nose.

Like a lot of parisiens, and like me, come to think of it, he wears black, top to toe, and has an easily composed face—not expressionless, just perhaps a little ironic or puzzled, a small smile at the corners of his mouth, curious, I guess, or maybe just hoping for something out of the way to happen right in front of him. He’s in the wrong place for that. In all the years I have come here, I don’t think I have ever seen anything you’d call odd or unexpected, the only occasional drama being a dropped glass or a dish or two. A couple of times, the café has been spiffed up, but Jean-Claude arranged the rehab so carefully that he was only closed for a day and a half each time, and then the difference was noticeable only if you happened to study the paint on the elegant moldings by the ceiling or noticed that the curtains, red and tan as always, were a little brighter and stiffer looking, new, not washed. Jean-Claude likes continuity and, not hard to guess, peace and quiet in his café. Wrong place for an adventure.

That suits me fine, even if the man in the mirror seems a little antsy. I know how he feels. It’s in our nature to be doing, if only observing something passively, taking it in, thinking it over. It’s not easy to sit still, hands folded, feet not tapping, just letting the world and time pass. But I also know something else, about myself if not about all my neighbors on earth. There are times when what I need is nothing, the happening of nothing which, just as the famous “no comment” is a comment, is something happening after all, just dull. It has the mysterious restorative power of sleep while fully awake and alert, without the profound puzzle of dreams or the powerful desire to escape from our consciousness. Even so, I notice that I too am fidgeting a little, fiddling with my glass, my little spiral notebook, the salt dish on the table.

Years ago, I hurt my back badly and spent ten days in bed: I couldn’t even prop myself up enough to read. It had the same effect then, the contemplation of nothing, and led me to make up my mind to leave a job I hated and to make some serious changes in my life. After staring at the ceiling for a few days, you discover everything that you are ever going to discover about it and somehow the mind gets down to serious business, approaching it sideways, perhaps, or on all fours, but getting to the point, finally and seriously. That explains, I guess, why I am feeling down today. The obvious—like the ceiling—just hit me square in the face and I’m looking at it.

I am often happier in Paris than in Washington where I live now or in the New England towns and cities where I spent most of my life or in New York where I was born and no longer feel welcome or remotely at home. But Paris isn’t home, either. A correspondent from an online forum just told me the other day that I’ve been spending too much time in Paris, become too typically parigot aggressive, but he’s not really serious and, anyway, he doesn’t know me. Perhaps I have been too much a gypsy: I don’t know where I belong or if I belong anywhere at all. Today I know I’m in the wrong place, not just the wrong place for something exciting or interesting to happen, but the wrong place for me, no matter how comfortable the café is, no matter how welcoming Jean-Claude is as always, no matter how good the weather outside on the streets, no matter dinner with friends on the agenda for this evening.

I sigh and catch the man in the mirror again. Jean-Claude is standing by his table and—should I be surprised?—I hear them across the room and through the mirror. Well, the man says, it’s time to go. Jean-Claude says it’s still early. No, I mean go home, the man says, time to go home. Jean-Claude, not a simple man at all, doesn’t ask for home’s coordinates or postal code. He smiles sympathetically and shakes hands—à bientôt. Yes soon, is the answer, soon I hope. On the street I promise again that I’ll stop in as soon as I can, first thing, next time.

© Joseph Lestrange is an American writer who has contributed many stories about Paris life published by BonjourParis, which you can read by clicking on his name.

Would you like to submit a story or request a story topic? Your stories & ideas welcome.

NEW: exclusive content for subscribers in every newsletter. Subscribe for free.

Top 100 Readers’ Favorite Amazon.com Items. (Please wait for Amazon.com widget to load)

Direct airport transfer service

PARIS SHUTTLE is a leading Paris airport transfer service. Book your airport transfers in advance online for direct to-your-door service and check the current discount available to BonjourParis readers who book using our link.

More in Bars in Paris