The National Library of France. Always on the move.

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

“A room without books is like a body without a soul”. The Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BNF) certainly has its soul, a great and generous one. According to the library statistics, it offers its readers about 14 million books, and 250,000 manuscript. Officially created by the merger of the old National Library with the new Library of France in 1994, the BNF is spread out over five sites: François-Mitterrand, Richelieu, Arsenal, The Opera Library and Maison Jean Vilar in Avignon, as well as Gallica, the digital collection.

The beginnings

It all started in the Middle ages. In 1368, Charles V installed his rich private collection in the Louvre, but it was dispersed after his death. It is Louis XI who can be considered the founder of the royal library, as he laid down the base for its continuity in the second half of the XVth century. At first, there were only manuscripts. Then, in tune with the growth of the the French monarchy, the collection began accumulating books (after the invention of the printing press in 1450), engravings, prints, medals, and coins. The collection expanded due to acquisitions, gifts, trophies, and confiscations. If there is a date worth noting in the library’s history, it is December 28, 1537, when king humanist Francis I required publishers to deposit a copy of every book printed in the kingdom in the library. This certainly helped the collection grow.

It all started in the Middle ages. In 1368, Charles V installed his rich private collection in the Louvre, but it was dispersed after his death. It is Louis XI who can be considered the founder of the royal library, as he laid down the base for its continuity in the second half of the XVth century. At first, there were only manuscripts. Then, in tune with the growth of the the French monarchy, the collection began accumulating books (after the invention of the printing press in 1450), engravings, prints, medals, and coins. The collection expanded due to acquisitions, gifts, trophies, and confiscations. If there is a date worth noting in the library’s history, it is December 28, 1537, when king humanist Francis I required publishers to deposit a copy of every book printed in the kingdom in the library. This certainly helped the collection grow.

So-called ‘double legal deposit’ (deposit by printers and booksellers) still applies nowadays and concerns all printed documents and graphic production.

When in Paris, stop by two principal sites of The National library: Richelieu, the most ancient and François-Mitterrand, the most modern.

Stop one: Richelieu

The history of this library is one on the move, due to a continuous search for space. Nowadays bounded by four streets, Richelieu, Colbert, Viviene and Petits-Champs, it took centuries to define and arrange this quadrilateral location in the 2nd arrondissement (district).

The history of this library is one on the move, due to a continuous search for space. Nowadays bounded by four streets, Richelieu, Colbert, Viviene and Petits-Champs, it took centuries to define and arrange this quadrilateral location in the 2nd arrondissement (district).

Colbert, the Minister of Finances of Louis XIV, had extended the royal collections and, because of a lack of space in the Louvre, installed them at rue Vivienne in two mansions that belonged to him – the first emplacement of the library in the quarter. A major period in the library‘s history, considered the golden times, is related to the abbot Bignon, the royal librarian. He enriched the collection and developed a system of departments, each directed by a librarian – the system survives today.

If from the end of the XVIIth century only a small circle of educated people had access to the library, by decree of 1720 it was to be opened to the public once a week in the morning. In 1721, Bignon started to transfer the royal collection in the ancient palace of the cardinal Mazarin. Over the following centuries the collection continued its growth, especially increasing after the confiscations during the Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars.

You will surely better understand this major problem of space shortage if you take a walk in the narrow streets of the area. Anyway, step-by-step, the library was appropriating local neighborhood, adding the gallery Mazarine, liberated by la Bourse in 1825, and mansion Tubeuf from the Treasury.

During the second half of the XVIIIth and the first half of the XIXth century there were proposals of many projects of serious enlargement and transfer, but none of them ever came to fold. (Pictured below: ‘The project of Etienne-Louis-Boullée. 1785’)

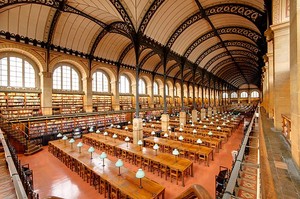

It was during the Second Empire (1852-1870) that the library acquired its contemporary look. Following the analysis of commission directed by Prosper Mérimée, Napoleon III ordered a reconstruction, but not the transfer of the site, and called it the Imperial National Library. The chosen architect, Henry Labrouste, was already famous for construction of the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève. His project, approved in 1859, would last until 1873. A major contribution by Labrouste is the reading room that bears his name. Room Labrouste, opened in 1868, became the symbol of the library. Built on a square plan, it was covered with nine domes of enamelled faience supported by sixteen slender columns. A semicircular apse completes this set. (Pictured below: H. Linton. Inauguration of the new reading room in June 1868)

It was during the Second Empire (1852-1870) that the library acquired its contemporary look. Following the analysis of commission directed by Prosper Mérimée, Napoleon III ordered a reconstruction, but not the transfer of the site, and called it the Imperial National Library. The chosen architect, Henry Labrouste, was already famous for construction of the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève. His project, approved in 1859, would last until 1873. A major contribution by Labrouste is the reading room that bears his name. Room Labrouste, opened in 1868, became the symbol of the library. Built on a square plan, it was covered with nine domes of enamelled faience supported by sixteen slender columns. A semicircular apse completes this set. (Pictured below: H. Linton. Inauguration of the new reading room in June 1868)

The architect Jean-Louis Pascal continued the work of Labrousse. He conceived and started the second most spectacular area the Oval Room. Its oval is 45 meters long and 34 meters wide. People working in the gorgeous place, you can still glance at it at least through the small windows.

The architect Jean-Louis Pascal continued the work of Labrousse. He conceived and started the second most spectacular area the Oval Room. Its oval is 45 meters long and 34 meters wide. People working in the gorgeous place, you can still glance at it at least through the small windows.

You can visit some temporary exhibitions, but mainly don’t miss the Cabinet of medals and antiques on the second floor. While walking up the monumental staircase, cast a look to the original plaster sculpture of Volter by Houdon, recently moved from the Honour Hall to the landing of the Cabinet because of reconstructions. The heart of the philosopher is said to have been put in the base of the monument. Some don’t believe rumours that the heart was there, others do and wonder if it was removed during the transfer of the sculpture.

Finally, the Cabinet! Integrated in the library as the Department of coins, medals and antiques, it has been open since the seventeenth century. It owes its birth to the Cabinet of French kings, which united several collections, especially that of the duke of Luynes. This wonderful little known museum has rare examples of Greek pottery, stones, coins, Roman marbles, but also ivories, bronzes and silverware and contains a number of symbolical objects for the French history, such as so-called bronze Throne of Dagobert dating to VII-IXth centuries.

Finally, the Cabinet! Integrated in the library as the Department of coins, medals and antiques, it has been open since the seventeenth century. It owes its birth to the Cabinet of French kings, which united several collections, especially that of the duke of Luynes. This wonderful little known museum has rare examples of Greek pottery, stones, coins, Roman marbles, but also ivories, bronzes and silverware and contains a number of symbolical objects for the French history, such as so-called bronze Throne of Dagobert dating to VII-IXth centuries.

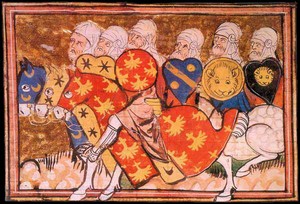

Wait! Before leaving the library, take a look on the Department of Manuscripts. Its pivot possesses 10,000 illuminated manuscripts, thus, the incomparable collection of medieval art. Thanks to famous donations, especially that of Victor Hugo who served as an example, the department has a gorgeous collection of modern literary manuscripts.

Wait! Before leaving the library, take a look on the Department of Manuscripts. Its pivot possesses 10,000 illuminated manuscripts, thus, the incomparable collection of medieval art. Thanks to famous donations, especially that of Victor Hugo who served as an example, the department has a gorgeous collection of modern literary manuscripts.

It’s incredible, but the library hasn’t stopped moving! An ambitious renovation project was launched in 2010 and should be completed in 2017. Among announced aims are opening of the Richelieu Library to a wilder public and making it a major center for research. Good luck! As for us, let’s move to the 13th arrondissement, hosting the new site.

Stop two: Mitterrand

On July 14, 1988, the socialist President François Mitterrand announced the construction of the largest and the most modern library of the world. It was to be one of the ‘big projects’ of his presidency. In 1989, the international jury selected four projects, distinguishing particularly one of them, which was selected by the president. Its author, architect, who was to change so much the panorama of East Paris, is Dominique Perrault (you can visit his site, if interested in his works).

Four immense towers (79 meters in height), each in form of an opened book, proudly soar on the riverside. A creation of urban art, but still in relation with nature, as a grove is situated in the internal cour, among the tours. Based on a stage with an ancient pride, with the same desire to soar towards the sky as Gothic cathedrals, with a modern fascination for minimalism, transparency and serenity, the Mitterrand library is never the same, it constantly changes its looks, sparkling in the reflects of the sun or in the drops of rain. But, be careful, visitor, to get to the treasures, you have to surmount the wind’s rushes, while climbing the stages, and not fall down, when stepping on slick exotic wood.

Four immense towers (79 meters in height), each in form of an opened book, proudly soar on the riverside. A creation of urban art, but still in relation with nature, as a grove is situated in the internal cour, among the tours. Based on a stage with an ancient pride, with the same desire to soar towards the sky as Gothic cathedrals, with a modern fascination for minimalism, transparency and serenity, the Mitterrand library is never the same, it constantly changes its looks, sparkling in the reflects of the sun or in the drops of rain. But, be careful, visitor, to get to the treasures, you have to surmount the wind’s rushes, while climbing the stages, and not fall down, when stepping on slick exotic wood.

Never had France invested so much in the construction of a building with cultural aims, but this time such heritage as all printed and audiovisual production of the nation was at stake. This decision was not an easy one, and was taken only after fierce debates, as firstly it was previewed to transfer from Richelieu site only documents of the XXth century.

French people have always had a taste for the mockery, not only the BNF was nicknamed TGB, The Very Big Library, but also, for example, TGB, The Very Big Stupidity (très grosse bêtise). Jean-Marc Mandosio, academic and essayist, wrote a book « The collapse of the very big National library of France » criticising all, from pomp and indeterminacy of the governmental project of the « library-computer » to the smallest details of new regulations, difficultly understood by readers used to old libraries. Inveterate visitors of the library do like Mandosio. Fortunately, without losing their sense of criticism, they still come to work there, to enjoy its spaciousness and comfort.

The reading rooms are divided in two parts: haut-de-jardin and rez-de-jardin, the first one occupied mostly by students, and the second one by scientists (a contradiction with the first idea of the democratic library opened to everybody).

Don’t be lazy to ascend the stairs, and don’t be afraid to enter even if you don’t come for reading. Go inside, cross the halls, see the huge Globes of Louis XIV, visit a temporary exhibition.

Don’t be lazy to ascend the stairs, and don’t be afraid to enter even if you don’t come for reading. Go inside, cross the halls, see the huge Globes of Louis XIV, visit a temporary exhibition.

Then, if it’s sunny, you can take a pause sitting on the stairs, otherwise, don’t miss a film in the cinema just nearby (MK2), or cross the river to go to the Cinémathèque (51, rue de Bercy), if you prefer conceptual and independent movies. Or, after walking a bit, come to Bercy village with its tiny cafes and a huge cinema. So, feel free to discover Paris, different in every quarter!

P.S. If you feel like starting by virtual visit of the library, you can watch a small video (3 min 29 sec) on this link.

Photo credits: all are public domain images from Wikimedia Commons.

Subscribe for FREE weekly newsletters.

BonjourParis has been a leading France travel and French lifestyle site since 1995.

Readers’ Favorites: Top 100 Books, imports & more at our Amazon store

We update our daily selections, including the newest available with an Amazon.com pre-release discount of 30% or more. Find them by starting here at the back of the Travel section, then work backwards page by page in sections that interest you.

Current favorites, including bestselling Roger&Gallet unisex fragrance Extra Vieielle Jean-Marie Farina….please click on an image for details.

Click on this banner to link to Amazon.com & your purchases support our site….merci!

Lead photo credit : Portrait of François I (1494-1547), king of France, Jean Clouet, Public Domain

More in French history, histoire paris, library, Monument, Museum, national library, Paris, Paris history